What Is a Change Order in Construction?

In construction, a change order refers to the documentation of an agreement to add or subtract work, alter the design, revise the schedule, modify the price, or deviate from the original project in some other way.

In the context of this change order, an owner and a general contractor (or a general contractor and a subcontractor) agree on a particular scope change and record the details in the change order document. The construction change order represents an amendment to the original contract, which defines the project’s scope of work and references plans, drawings, and specifications.

Change orders in construction are very common, and occur in almost every commercial and public project. Still, your goal should be to avoid them as much as possible, because change orders can result in delays and higher costs.

Changes to construction plans tend to negatively impact only one party. For example, an owner may miss the target date for a new building’s opening, or a contractor may end up having to use a more expensive material without receiving additional compensation.

Lots of different circumstances can necessitate change orders: For example, a contractor may discover that site soil conditions are less stable than the designers initially believed. Such a discrepancy will inevitably cause you to change your approach, and will likely require more work, time, and materials.

Another example: After a contractor has installed lighting fixtures, an owner may decide to upgrade the illumination of those fixtures. To formalize this change, the contractor would write a change order that addresses the removal of the original fixtures and the purchase and installation of the new fixtures.

Such changes can cause friction, and disagreements can undermine working relationships.

“Change order disputes can profoundly impact a project, especially if you stop work while the parties dispute the change order,” says construction attorney Colin McCarthy, Principal at Orange, California-based Lanak & Hanna. “If they are not resolved in a timely manner, change order disputes often cascade into project delays and additional costs for both parties.”

Reasons You Might Need a Construction Change Order

The long-term nature of the commercial construction process itself generally creates the need for a change order: significant discrepancies between the initial plans, designs, budgets, etc. and the actual circumstances (once work begins) are inevitable.

(If you are not familiar with the basics of construction management, see “Construction Project Management 101” for a complete introduction.)

In this interim (between the submission of the initial plans and the commencement of construction), more players get involved, including architects, engineers, and other design specialists. They work on different aspects of the project and seek to coordinate their efforts. In spite of these attempts to maintain order, however, once you increase the number of players and roles, you typically increase the complexity of the project. Growing complexity usually means the proliferation of design conflicts, specification gaps, and other disagreements and errors.

As these disagreements and errors accumulate, change orders inevitably pile up. General contractors and subcontractors use these documents not only to help price their bids during the bid prep process, but also to correct omissions, mistakes, and other problems that they discover during construction.

In addition, the need for change orders often arises because large, ongoing construction projects exist in a perpetually fluid environment: An owner’s requirements or financial resources may change; a freak snowstorm may halt work; an economic crisis may affect project funding; or a subcontractor may not be able to find qualified tradespeople. .

Here are the typical construction problems that give rise to change orders:

- Errors and omissions in plans and drawings

- Unrealistic budgets and schedules

- Design changes, including the addition of items and features

- The unavailability of workers or materials

- Unanticipated site conditions, such as unstable soil

- Substitutions of materials due to shortages or upgrades

- Conflicting or inaccurate specifications

- Technology changes

- Conflicts between the contract and project documents

- A poorly defined scope

- Financial problems on the part of the owner or the contractor

- Inadequate coordination

- Damage from inclement weather

- Quality issues and construction defects

- Regulation changes

Streamline Data Collection with Smartsheet Forms

Turn collected data into actionable insights instantly

Smartsheet forms capture consistent, accurate data and feed it directly into an organized sheet, giving you instant visibility. With customizable branding, conditional logic, and mobile accessibility, Smartsheet forms not only simplify data gathering but also allow your team to take action right away—whether you're tracking requests, collecting information, or managing fieldwork.

What Should a Construction Change Order Form Include?

A change order form should include a highly detailed description of the change and the new terms. It should also include other information, such as the new price, the name and address of the project, the owner’s name, and more.

At a minimum, all change order forms should identify the following:

- The name and address of the project

- The owner’s name

- The name and phone number of the person requesting the change

- A complete description of the planned work

- The price of the change (including a breakdown of the costs as well as the total)

- The signatures of all necessary representatives

- The signatures of the homeowners (in the case of residential projects) or other relevant third parties

- The date on which all necessary representatives (and other relevant third parties) sign the change order

- The revised project completion date

Change Order Process in Construction

Because change orders can have a major impact on a construction project’s costs and profitability, all concerned parties must follow a standardized change order process and make sure not to overlook any steps.

Here are the steps to follow when drafting a change order:

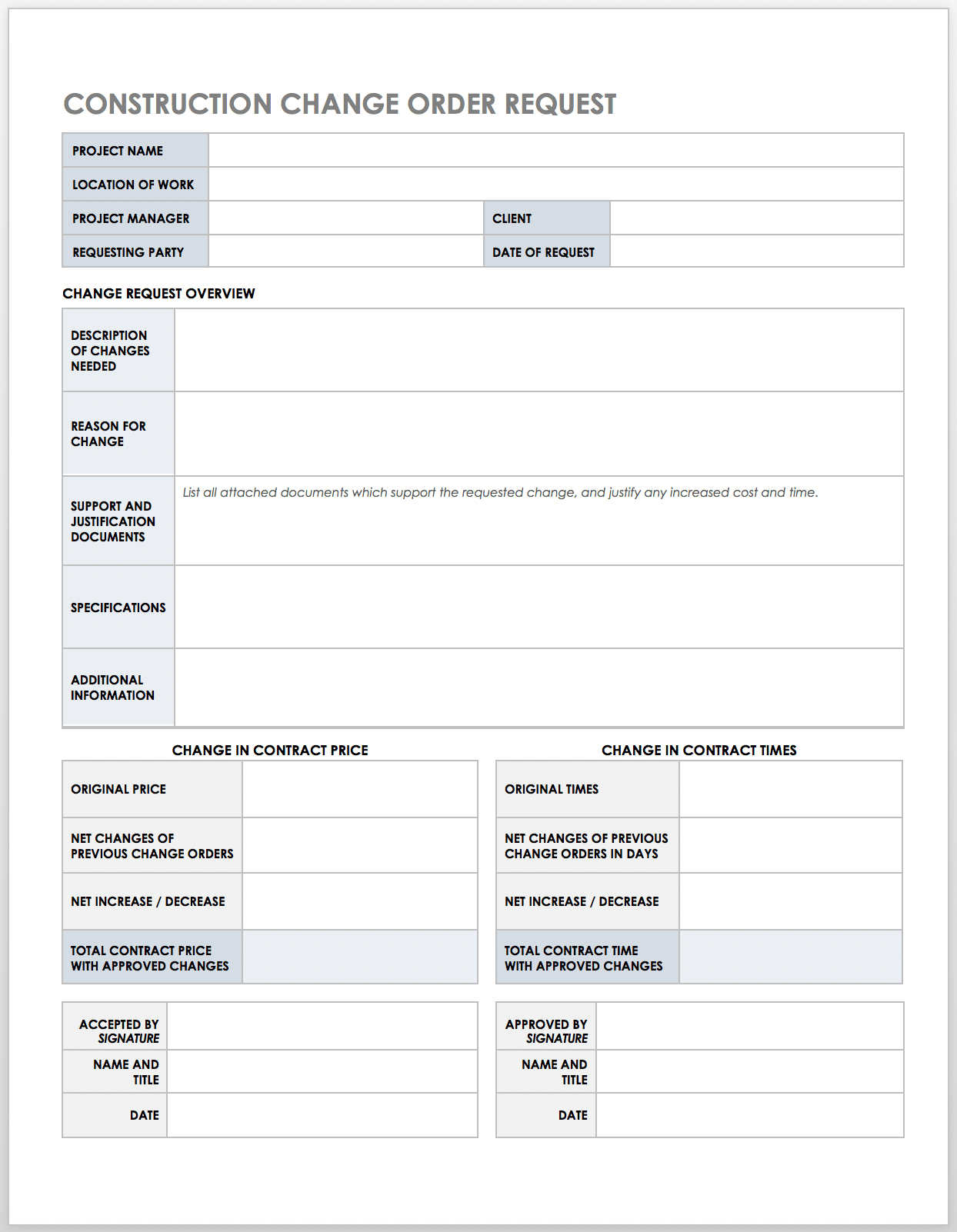

1. Use a Standard Process (Including a Template) to Ensure Consistency: You can find downloadable construction change order templates for all purposes by reading “Complete Collection of Free Change Order Forms and Templates.” Below, you’ll find a good example of a change order summary. It includes sections for all pertinent information, such as a description of the necessary change, supporting documents, and specifications of the change.

Download Construction Change Order Request Template

Excel | Word I PDF | Smartsheet

2. Meet with Other Stakeholders: Gather the owner, contractor, and subcontractor to discuss the change before you document it on your form. Try to reach an agreement on how the change will affect the cost and schedule. (Remember that oral agreements are not legally binding, so don’t rely on a conversation with the foreman.)

3. Define the Change: Using your change order form, summarize the revision. Include details regarding the change, any modification in material or technique, the reason for the change, and any new specifications. Make sure to submit the form.

4. Clarify the Impact on the Budget and Schedule. Make sure that the document clearly articulates any change in cost and time that the change will require. Also, show how the change will affect the project’s overall price and timeline. If there is no change in either the former or the latter category, make that clear as well.

5. Present to the Other Party: If you have agreed on the terms of the change, simply present the change order to formalize the addition of the document to the contract.

6. Negotiate More if Necessary: If the parties have not yet agreed on how the change will translate into dollars and days, further negotiations are necessary. These discussions may involve senior project managers, finance executives, and construction lawyers. If you are still unable to agree, the contractor may have to continue the work while reserving the right to seek compensation at the project’s conclusion.

7. Sign Off: Once you’ve reached a consensus, confirm that the change order document accurately reflects the final agreement, and authorize the change by having each party sign the document. Note: If you are unable to achieve a consensus, you must still perform the work (without receiving additional compensation until the project ends), if the contract language includes such a mandate.

8. Verify the Impact to the Project: Adjust the overall project schedule as necessary and make sure that you update all dependencies (other work that cannot begin until the change order-related job ends) and identify any conflicts.

9. Communicate with All Stakeholders: Share details of the change with all project participants, including field managers, the crew foreman, and subcontractors.

10. Keep Good Records: Retain all documentation and keep a construction change order log for invoices/payments, disputes, or audits. Tax laws, etc. may require you to save these documents for a period of time (a few years to more than a decade, depending on your location and whether or not your building is a government project). You an find a downloadable template for tracking construction documentation, contractor progress reports, and more in “Excel Construction Management Templates.”

Construction Change Order Form Pricing Considerations

There are three types of cost to consider when determining the price for a construction change order form: direct, indirect, and consequential costs. You can calculate those costs using either a forward or backward approach (described in detail below).

Research studies have found that, on major projects, the change order costs typically amount to 10 to 15 percent of the contract value. Moreover, these studies reveal that a greater number of changes means reductions in productivity of anywhere from 10 to 30 percent.

Additionally, timing can have a dramatic impact on the cost of a change order. For example, requesting a change order early on in the construction process (before a crew has begun to work on the item in question) will not cost you as much as requesting a change after a team has begun or completed work. Furthermore, the order will cost even more if the team has already completed work that is subsequent to and dependent upon the item in question. In this last scenario, the change will require that you rework the item (and all dependent items) that the team has already installed, thereby creating a chain reaction of additional costs.

In the case of any change order proposal, a contractor should itemize their prices in great detail. When you submit a lump-sum proposal to an owner, you deny them the transparency to do the following: see the reasoning behind the costs; make sure that there are no hidden costs, and confirm that the profit margin of the order doesn’t exceed that of the contract.

Categories of Construction Costs to Consider in Change Orders

As mentioned above, the three cost types that construction change orders must take into account are direct (which is the easiest type to understand), indirect, and consequential (the latter two can be very difficult to quantify).

- Direct Costs: These are the costs that are directly involved in implementing a change order. Some direct costs are obvious — materials, labor, and equipment. Others are not as apparent: professional fees for a redesign; fuel to run equipment; staff hours to coordinate a change and communicate it to engineers and site crew; fuel; security; project insurance; sales tax; permit fees; licenses; safety measures; cleanup; and utilities. Calculating certain direct costs in particular requires taking into account a wide variety of factors. Here are the methods for calculating various direct costs:

- Calculating the Cost of Construction Labor Components: Labor includes work hours and rates, labor supervision, and project supervision. This cost also includes benefits such as sick pay, insurance, and retirement, as well as employer taxes.

- Pricing Materials for Construction: To calculate the base cost of materials, use price quotations from vendors or actual costs. To this base cost, add the costs of transporting, storing, handling, and inspecting material.

- Assigning Costs for Rented and Owned Construction Equipment: When determining change order-related equipment costs, many factors contribute to your calculations. Most significantly, do you rent or own your equipment?

- Rented Equipment: In order to calculate the cost of rented equipment, first determine an hourly rate by multiplying the rental charge by the number of hours you need to perform the change order work. Then, add the operating costs, such as fuel and lubricant.

- Owned Equipment: If you own the equipment, specify your pricing method in the contract, unless you’ve already established your own equipment cost recovery rates for allocating equipment to a project. The recovery rate for such an allocation reflects the purchase price, sales tax, depreciation, cost of ownership (such as insurance and licensing, maintenance, overhauls, and repairs over a machine’s expected lifespan), and financing cost/opportunity cost.

If you do not have an established recovery rate, you can calculate one by consulting the retail rental rates of such industry references as the AED Green Book, Rental Rate Blue Book, and Army Corps of Engineers Equipment Rates.

To calculate a maximum hourly rate for the change order work, take the monthly rate and divide it by the 176 available working hours in a month. Typically, you must cap the rate at 50 percent of the machine’s market value at the time you first used it for a change order.

If your situation is not complex enough to merit detailed calculations, a good rule of thumb is to price the equipment you own at 50 to 60 percent of the retail rental rate.

Whether you rent or own your equipment, you need to add operating costs, including fuel and oil, parts, fluids, shop space, and storage. In addition, when you are calculating equipment costs in the context of change orders, you must apply different rates based on the status of the machine under consideration. In other words, your rate for a specific machine must reflect its level of wear and tear (i.e., is it on standby, idle, or active?). When you calculate the rate for standby equipment (i.e., available, on-site equipment that you are not currently running or using), that rate typically includes depreciation, cost of capital, overhead, and indirect costs. When you calculate the rate for idle equipment (meaning available, on-site equipment that you are currently running, but not using), that rate includes depreciation, cost of capital, overhead, indirect costs, labor and parts for scheduled overhaul, and fuel.

- Indirect Costs: Indirect costs include overhead, profit, and markup. Although these costs are only indirectly related to change orders, you must account for them in your change order pricing.

- Overhead: This refers to the administrative expenses that you incur running your overall business, but that are not allocable to any individual project. This category includes office rent, office equipment, office utilities, management and administrative staff salaries and benefits, advertising, taxes, training, business licenses, staff vehicle insurance, legal and accounting costs, association dues, and service or warranty work on current equipment and other structures.

Typically, large companies have higher overhead costs than do smaller firms. To calculate your overhead percentage, divide your total company revenue by your total overhead costs:

Total Annual Revenue $ ÷ Total Overhead $ = Overhead %

(You usually spell out the profit and markup percentages in the construction contract.)

But, many contractors lack a strong grasp of their indirect costs and, therefore, underprice them, experts say.

For example, construction cost experts consider 10 percent to be a standard overhead cost. However, a study on change order-guidelines by ELECTRI International (The Foundation for Electrical Construction) found that electrical contractors spend an average of 19.16 percent to run their business.

Using the conversion formula below, this 19.6 percent for general business overhead yields 23.7 percent for the overhead that directly concerns change order costs. This discrepancy between percentages occurs because you are calculating your overhead percentage for direct change order costs on the basis of total sales or revenues:

Overhead % ÷ (1 - Overhead %) = % of Direct Change Order Costs

Plug that 19.6 percent for general business overhead into the above formula, and you will yield that 23.7 percent for the overhead that directly concerns change order costs:

0.1916 ÷ (1 - 0.1916) = 23.7% or 0.1916 ÷ 0.8084 = 23.7% - Profit: There are two types of profit to consider regarding indirect costs: net profit and gross profit.

- Net Profit: This refers to the amount that the contractor makes after subtracting all costs and expenses, including overhead. The average net profit is five to 10 percent of all revenue.

- Gross Profit: This refers to the amount that the contractor makes before subtracting all costs and expenses, including overhead.

- Markup: This refers to the amount that the contractor adds to costs (both direct and overhead) to arrive at a profitable selling price. You must also factor the markup into change order prices. A common industry standard for markup is 15 percent. Much like the concept guiding the formula above (the one for calculating the overhead percentage of direct change order costs), the markup percentage must exceed the desired profit margin percentage in order to achieve that desired profit margin.

For example, to achieve a 20 percent profit margin, you must mark up costs by 25 percent; then, you price the change order accordingly. The discrepancy between these two percentages exists because, while profit margin percentage increases at a linear rate, the correlating markup percentage increases at a rising rate.

The competitive landscape and the economic climate both influence pricing. Therefore, the markup and profit margins that you apply to your bids should carry over to your change order pricing.

For example, in a highly competitive market or during an economic downturn, a contractor may price their bid with a lower-than-standard profit margin. Similarly, when stiff competition and price transparency make owners resistant to higher markups on commodity items, a contractor may apply only a nominal markup to materials.

- Overhead: This refers to the administrative expenses that you incur running your overall business, but that are not allocable to any individual project. This category includes office rent, office equipment, office utilities, management and administrative staff salaries and benefits, advertising, taxes, training, business licenses, staff vehicle insurance, legal and accounting costs, association dues, and service or warranty work on current equipment and other structures.

- Consequential Costs: These are the indirect costs (specifically hard and soft expenses) that you incur as a result of a change order. These costs are “consequential” because they are the direct consequence (i.e., the ripple or cumulative effect) of the change order itself.

Consequential costs include such factors as project delays, overtime, training, morale, crew reassignments, and inefficiency. These costs also include labor productivity losses from the stacking of trades (the phenomenon in which multiple subcontractors work in a limited space). In turn, trade stacking introduces safety hazards and other obstacles, including increased difficulty in accessing materials.

Industry literature, surveys, court cases, and case studies provide guides for calculating the impact of such change order-related factors. Among these resources are the Mechanical Contractors Association of America’s Toronto Change Order Protocol and Andrew Civitello’s Contractor’s Guide to Change Orders.

Hanna Consulting Group, Inc. and its President, Dr. Awad Hanna, Professor and Chair of the Construction Engineering and Management Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed a method called the Cumulative Impact Approach. The method determines the probability that a change order will impact an overall project. Hanna also invented the Measured Mile Approach, a method for quantifying the costs of such a change order impact on an overall project. In addition, the firm also worked on a method for quantifying the impact of trade stacking.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and various other industry entities have also developed methods for calculating consequential costs (i.e., the cost of each factor that has an impact on productivity).

You estimate the cost of each of these factors based on their impact: minor, average, or severe. For example, a severe stacking of trades results in a 30 percent loss of productivity, while minor fatigue results in an eight percent reduction in productivity, according to ELECTRI International’s research.

When you calculate consequential costs for a change order, be prepared to support your numbers with authoritative references. This way, if the change order becomes the subject of a dispute, you’ll be able to prove that your calculations were fair and reasonable.

Pricing Models: Forward vs. Backward Pricing of Construction Change Orders

The pricing approach on construction change orders depends a lot on timing. Forward pricing occurs in advance of the change order work, while backward pricing takes place after you’ve performed at least some of the work.

When applying backward pricing, you have access to actual first-hand experience with which to calculate a price; on the other hand, when applying forward pricing, you must rely on estimates and contract norms.

Both pricing approaches take direct, indirect, and consequential costs into consideration. And, regardless of if you use forward or backward pricing for your construction change order, you must also identify the time and productivity impacts on cost.

In the absence of actual data, the cost flow technique can help you calculate your forward pricing. Often represented as a graph, cost flow analyzes construction spending over time, showing you how much you must budget and spend at each crucial juncture in order to complete construction as you’ve planned. Consider both the direct and consequential costs when performing these calculations.

Cost flow is often confused with cash flow, which is money that is coming in to or going out of a business (or, here, a construction project) over time. By comparing cash flow to cost flow in the context of a construction project, you can determine — as you incur costs — whether or not money will be available. If you find that money will not be available, then you may need to make changes to the project.

In the case of a change order, owners and contractors can compare the revised cost flow to the original cost flow in order to identify the impact of the change. Doing this can clarify pricing. But, in order to make this comparison useful, you need to have detailed data on the productivity (or the lack thereof) that results from the change order.

Common Construction Change Order Issues that Lead to Disputes

Construction change orders are frequently the subject of litigation, often due to disagreements between contractors and owners over whether the change requires a revision to the compensation or schedule, or whether such change is already covered under the original contract.

According to the Arcadis 2020 Global Construction Disputes Report, the global average value of construction disputes was $30.7 million, and the average duration of those disputes was 15 months. Therefore, both owners and builders are strongly motivated to understand the issues that commonly cause disputes so that they can seek to avoid them.

The seeds of these disputes often lie in the content of the contract and bid documents themselves, because the nature of such content is not apparent to the parties when they sign. When you don’t clearly articulate certain aspects of your project from the outset, you often discover later on that your initial plans, designs, specifications, etc. require changes.

Here are some common causes of construction change order-related disputes:

- Incomplete Design: When plans and specifications contain mistakes, inconsistencies, or insufficient detail, the contractor may not be able to price the work accurately or fully execute it. Examples include inconsistencies among specifications, such as that between initial and final finish schedules.

- Poor Design Coordination: Architects, engineers, and consultants may each assume that one of the other parties is handling certain aspects of the work, so gaps in plans arise. Or, each party’s designs may conflict with one another, making it impossible for contractors to determine intentions or resolve issues.

- Specification Issues: Specification problems often stem from using boilerplate language, failing to account for specification differences among manufacturers, using out-of-date specifications, and listing component requirements that do not match a product on the market.

- Schedule Speed-Up or Delay: After the start of construction, an owner may decide that they need an earlier completion date, but may feel that such an acceleration should not incur an extra cost. Conversely, a contractor may be unable to meet a deadline, but still argue for the same compensation, pleading special circumstances.

- Inadequate Disclosure and Unknown Conditions: Whether due to a deliberate lack of disclosure or an honest inability to know beforehand, a discovery of a problem after work is underway can lead to a fraud claim. For example, a contractor or owner may not have been aware of poor subsurface conditions at the time of bidding. Or, perhaps, one party was aware, but chose not to disclose such information.

- Changes on the Part of the Owner: A contract generally allows the owner to make changes as long as they compensate the contractor for any increased cost. Sometimes, however, these changes form the basis of a dispute: The owner may argue that such changes don’t justify additional compensation, and the contractor may argue the contrary.

- Unfair Restrictions: This phenomenon occurs when a government or other public project’s design and construction documents place unfair restrictions on a contractor. Such regulatory violations include requiring a contractor to use a proprietary option or restricting a contractor’s supply source.

- Unwritten Orders: While it is crucial for contractors to include contract provisions that call for the actual writing of a change order regarding any revision or additional work, field conditions, urgent circumstances, or simple carelessness can make it difficult to follow this step. By accepting merely verbal orders, you risk waiving certain contractual rights.

- “Requiring written change orders protects both contractors and owners from future disputes,” explains Houston litigation attorney Robert Burford, Founding Partner of Burford Perry. “Contractual provisions that require any change orders to be in writing are enforceable. Therefore, it’s a best practice for a contractor to include such provisions in their original contract. The contractor must also mandate the following of these provisions throughout construction, or they risk waiving those provisions.”

- However, attorney Kevin Bonner, a litigation and construction specialist at Fennemore, says that many courts will not enforce this provision against a contractor that adds value to a project: “For example, if a court finds that an owner has actively waived or rescinded a written change order requirement as a result of deciding they need a change and/or verbally directing the work, then that court may not enforce such a provision against the contractor,” he says. “In order to avoid surprises and disputes, both owners and contractors should strive to communicate regularly and document all changes in writing, including how a change will affect the contract price and time for completion.”

Construction Change Order Best Practices

While every project is unique, following best practices can minimize a wide variety of problems concerning construction change orders. Such problems include disagreements over cost and scope.

Here are some best practices from the field’s top experts:

- Make Contract Terms Fair and Clear: Defining project scope clearly and in detail in the documents can prevent change order disputes. Making sure that the terms are fair is also crucial to avoiding such disputes. Many large owners and developers push for preferential contracts that limit their liability regarding payment for changes, which is exactly why contractors must strive for contract language that is clear and equitable. Moreover, because many courts are reluctant to enforce provisions that they perceive as unfair, it is essential to create a lucid, comprehensive contract.

- “The best way to avoid disputes over change orders is to be proactive,” recommends attorney J.R. Skrabanek of Thompson & Skrabanek in New York. “That is, the parties are best served by establishing clear change order terms and procedures from the outset. Being clear upfront prevents headaches as the project progresses. It also helps align the parties' expectations vis-a-vis each other and the project.”

- Incorporate Realistic Change Order Clauses: Make sure the change order authorization clause is realistic. In such a clause, a party often requires authorization from a person who is off site and possibly even in a different time zone. Therefore, you should include an alternative procedure that identifies a secondary authorization contact, should the need for a time-sensitive change arise. Using this type of provision makes it possible both to pay the contractor during unforeseen, pressing circumstances and to protect the owner from excessive costs.

- Consider Ways to Keep the Peace: Delays and work stoppages are major sources of change order disputes. And, these interruptions and suspensions often occur because the payment terms of most contracts force contractors to execute changes, regardless of their overall compensation. As a logical consequence of such a pro-owner arrangement, contractors shoulder tremendous financial stress — this emotional climate, in turn, often leads to disputes. You can mitigate the potential for such problems by including certain language in your contract: State that the owner will pay a specified percentage (such as half) of all change order disputes that occur during construction; you should also articulate that both sides reserve the right to dispute each matter.

- Agree on Some Pricing Standards: Once an owner enters into an agreement with a contractor, they renounce their right to accept competitive bids from other contractors. As a result, the contractor sets their own prices for change orders, which can often lead to the owner’s accusations of price gouging. (In such a circumstance, the owner often suspects that the contractor is trying to recover losses on other parts of the project or angling to improve profitability via change orders.) In order to avoid such disputes, make sure you include the following information in your contract: a detailed schedule of the project’s labor, profit, overhead, and markup rates.

- Be Familiar with Change Order Requirements: Before work begins, re-review the contract and be aware of any requirements around the time boundaries for change orders as well as format, contents, and approval process for change orders. Deal with change orders promptly.

- Identify Issues Before You Begin: Before your project starts, be sure to revisit the plans and specifications in order to address any ambiguities, errors, omissions, and conflicts. Also, make sure to present any change orders right away, because doing so after construction begins increases the likelihood of cost overruns, schedule delays, and friction between the owner and contractor.

“Spending additional time at the front end of a project can go a long way toward minimizing change orders over the long haul. Use this time to look critically at the work, drawings, and details, and to ensure that the contractor’s bid clearly includes or excludes certain items,” says McCarthy of Lanak & Hanna. - Understand How Liens and Similar Tools Work: If you’re a contractor and you can’t resolve a dispute over a change order, you have a number of legal options. You have the right to use a mechanic’s lien (which gives contractors and laborers a security interest in the property in case they don’t receive payment), a stop notice, a bond, or a warranty claim, as long as you do so within the required time limits. Timelines vary by jurisdiction.

Other laws regarding liens also vary by jurisdiction. Some states require you to send a preliminary notice to the owner, lender, and general contractor (if applicable), stating that you are working in order to preserve your lien rights. California law requires general contractors to serve a lien 20 days prior to the first provision of materials and labor.

Once you have a mechanic’s lien in place, you then have the right to send a notice of intent to lien, should the owner pay late or fail to pay altogether. The mere act of sending this notice may itself prompt payment.

If the owner does not pay, a general contractor in California has either 90 days from completion of the project or 60 days from when an owner files a notice of completion or cessation (work stoppage for another reason such as a pandemic) to file a mechanics lien with the county recorder in the county where the property is physically located. For subcontractors, this period shortens from 60 days to 30 days.

In an example of the use of a lien in a dispute over change orders, HVAC subcontractor Dynamic Systems sued general contractor Skanska USA Building Inc for $4.3 million in November 2019, claiming it was not fully paid for work on a county medical facility in New York State. Dynamic claimed that change orders altered the scope of work, raising the price of its work from $17.8 million to $22.5 million. The company said that Skanska approved all the change orders but had not paid. Dynamic filed a public improvement lien for $6.1 million before construction was complete, which Skanska handled with a lien discharge bond so the facility could open. In its lawsuit, Dynamic asked the court to uphold the lien and award it costs and interest. - Improve Change Order Efficiency with Technology: Use construction project management software, takeoff and estimating software, or building information modeling (BIM) tools to automate and streamline the change order creation and management process.

- Communicate Regularly: Organize stakeholder meetings at the beginning, end, and throughout the life of the project to make sure that everyone is up to speed on the scheduled work. Stakeholders include the owner/client, general contractor, and subcontractors.

- Bring in Fresh Eyes: Hold peer or third-party reviews of drawings, specs, and other important documentation to make sure nothing is missing or incorrect.

- Stay Organized: Create and use checklists of the material you need to include in drawings, specs, and contracts.

- Keep Learning and Provide Training: Attend workshops and training on document quality and development, so everyone knows what processes to follow and information to include.

- Require Accountability: Don’t propose or accept open-ended change orders without any set deadline or budget limit.

- Require Contractors and Subcontractors to Provide Documentation: Ensure that subcontractors provide clear documentation of hourly rates, material costs, and quantities of any extra work. If possible, have them provide photos and video of their work along the way.

Change Order vs. Construction Change Directive

Construction changes are sometimes too contentious for the owner and contractor to reach an agreement on together. In this situation, the owner and architect may write a construction change directive that they impose on the contractor.

The architect decides the contractor’s compensation for the new scope of work, which may be nothing. This move is also called force account work. Unsurprisingly, construction change directives frequently injure relationships among the parties, cause hostility, and lead to lawsuits.

Contractors often wonder when and under what circumstances they can refuse to accept a change order. The cardinal change doctrine protects contractors in extreme cases: It holds that if the owner imposes changes that fundamentally alter the scope of work, the contractor has the right to break the contract. The contractor has to prove that the change qualifies as a “cardinal change” (a fundamental change to the project) — for example, if an owner hired a contractor to build an ice skating rink, and then decided to build a movie theater instead. Under these circumstances, the contractor can seek damages and is not in breach of the contract.

Courts will generally find these cardinal changes valid if the change substantially increases the amount of work required of the contractor, significantly alters the type of work, and entails a major change in project costs.

”Even though an owner has authority to require changes in the work, it is not unlimited. The cardinal change doctrine offers protection to contractors from overreach,” notes attorney David Reischer, CEO of LegalAdvice.com.

Reasons for Engineering-Related Change Orders

In the context of construction projects, engineers play a leading role. They are responsible for a great deal of the technical work that goes into building a structure, including designing key building systems, determining the right construction method, and ensuring that the work meets quality standards. Engineering-related changes often lead to change orders.

Here are the major reasons for engineering-related change orders:

- Adjustments for Costs of Fuel and Materials: Having to make these adjustments is a common cause of change orders. However, these adjustments are difficult to control for, because the prices for fuel and materials fluctuate with the market.

- Errors and Omissions in Contract: Omitting significant information from your contract can have a seriously negative impact on your project. Make sure to partner with highly experienced professionals in order to create and verify your contracts.

- Problems with Utilities: Having conflicts regarding utility designs, plans, or facilities can cause delays or require adjustments to the plans.

- Geotechnical Problems: The discipline of geotechnical engineering concerns the investigation of ground conditions in order to determine risks and design adequate foundations. Encountering problems in this area of a project can cause delays, work stoppages, or the need for redesigns. Geotechnical construction issues include the discovery of unforeseen soil and rock conditions.

- Owner/Client Additions: When an owner or a client adds elements to a project after construction is already underway, engineers may need to redesign plans and specs. Do your best to work out all the details ahead of time, so there are no surprises.

- Environmental Problems: Any time an owner requests changes, it’s imperative to consider the potential impact on the environment. Proposing changes that are going to interfere with environmental regulations or other protective measures can cause delays or the need for redesigns.

For more resources, download from our selection of free construction work order templates and forms.

Streamline the Change Order Process with Smartsheet for Construction

From pre-construction to project closeout, keep all stakeholders in the loop with real-time collaboration and automated updates so you can make better, more informed decisions, all while landing your projects on time and within budget.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.