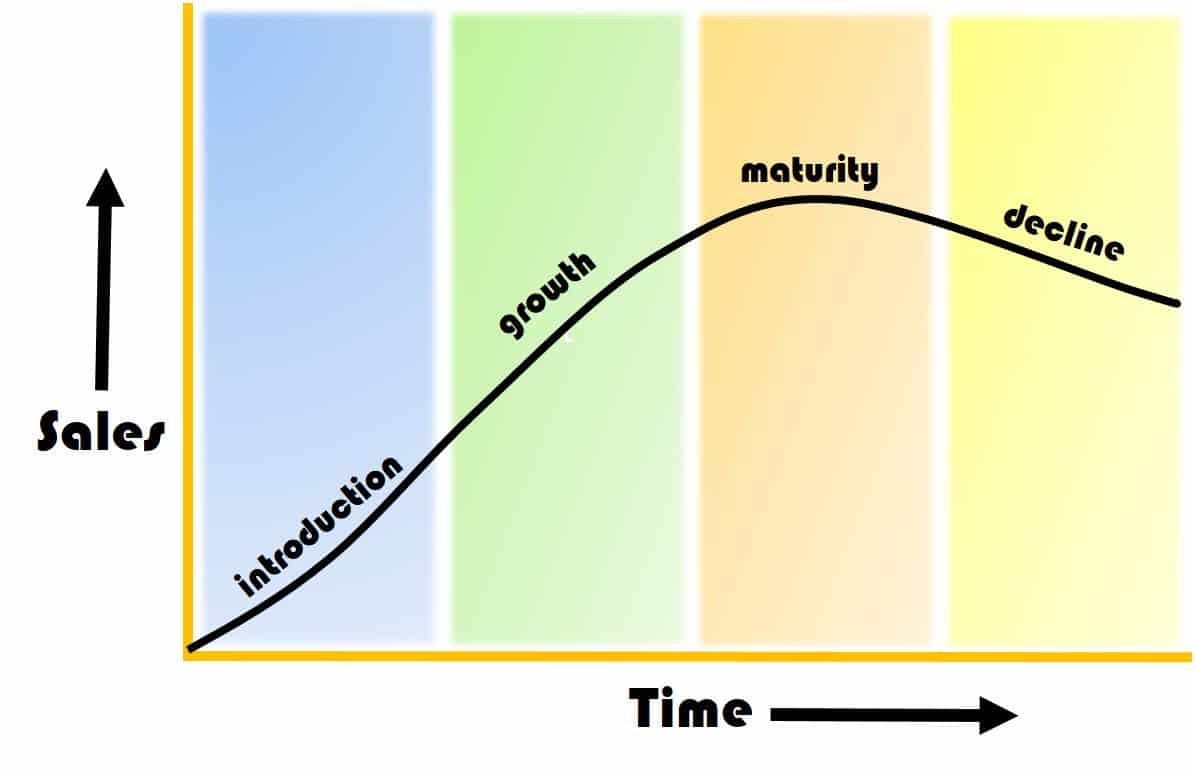

What Is The Product Life Cycle?

The product life cycle (PLC) is the pattern of stages that a new product or service goes through in its lifetime. Products have a limited lifespan and variable sales and profit margins based on their place in the life cycle. These stages include introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. How you market your product and the marketing mix you use depends on where your product is in the PLC. A marketing mix is all of the elements in the marketing plan that get your customers to buy your product. These elements include things such as the product itself, the price, promotion, place, and physical environment. Marketing in PLC theory must take four features into account:

- The demand for the product

- How you manufacture the product

- The international market competition

- The marketing strategy

We use PLC because there are changes over the product’s lifespan - with the product itself, the market, and the competition. We understand that products have limited lives in the marketplace and that each stage of life poses a unique challenge. Moreover, the profits for each product change based upon their current stage, and as a result will require different levels of strategies for marketing, manufacturing, human resources, and purchasing.

When you review all of the strategies that you use as your product goes through this life cycle, you are conducting product life cycle management (PLM). The goals of PLM include pulling together all of the resources for the product: the people, systems, data, and processes. You must understand your product in order to ensure that it gets to market when it needs to, is high quality, has low prototyping costs, and can be sold in multiple markets. For more information on PLM, see our new comprehensive page on PLM.

What Are the Product Life Cycle Stages?

Although there are some patterns that can help you determine where your product is in the cycle, determining its stage with accuracy is a bit of an art form, especially when your product is transitioning from one stage to the next. Further, for each company and each product, the length of time spent in each stage will differ. For example, Coca-Cola was introduced in 1886. It has had a phenomenally long PLC, with the majority of those years spent in the maturity stage. However, with recent sales slumps and a worldwide change in nutritional behavior, analysts are unsure if it is still in the maturity stage or is finally entering the decline stage. If you perform your PLC analysis properly, it will give you a constant scan of the market for your product and allow you to correct your course as soon as possible. For Coca-Cola, this could mean a novel advertising campaign to increase sales or accepting that their product is getting ready to retire.

The Introduction Stage

Also known as the market development stage, this stage is arguably the most expensive. The introduction stage occurs when a company launches a new product. Customers are unaware of the product. Sales are low at this point, but a lot of money may have already been spent on research and development, testing, and marketing. This is the heavy marketing stage. An example of a product in the introductory stage is holographic projection. Now, holographic projection technology is too expensive for the average consumer. For the marketing mix, you want to focus on:

- Setting the product branding and quality

- What price you need to set to either recoup your costs or penetrate the market

- Being cautious in your distribution until your product has a foothold in the marketplace

- Building product awareness and education

- The strategies to consider adopting to introduce an emerging product successfully include:

- Giving discounts to your distributors

- Building unique, novel features into the product to attract attention

- Encouraging new people to try your product with incentives such as money back guarantees

The Growth Stage

Also known as the market growth stage, this is when the sales finally take off. The marketplace is aware of the product, accepts it, and you start seeing profits. Your market shares are also doing well at this point, and you work on building brand preference in the marketplace. You are now able to maximize your investment in promotion to take advantage of this stage. Your production costs go down during this stage because you are not only more efficient, but your demand has increased. One product that is currently in the growth stage is tablet personal computers. The market for this convergent technology is still expanding and the product itself is still trying to reach a stable platform. For the marketing mix, you want to focus on:

Maintaining your product quality, but looking to add more features or services (if possible)

- Maintaining your pricing

- Adding distribution channels

- Advertising to a wider audience

In the growth stage, consider the following strategies to increase your sales:

- Supply excellent customer service

- Expand your distributors to make your product available more places

- Lower the cost of the product

- Market your product with a comprehensive brand image

- Consider different price points and features that can attract other markets

Your company can plan for growth. Using the product-process matrix (PPM) and planning for both changes in products and processes, your company can make decisions based on the four types of growth:

- Sales Volume: A simple increase of your current products within the marketplace. You are simply selling more.

- Product Line Expansion: This growth occurs when your company uses your current process structure to expand your line within your current market. For example, you are adding a slightly different model to your line.

- Process Structure Expansion: Also called vertical integration, this growth occurs when your company either expands into more steps on a production path or combines stages of production. Mergers of companies, such as the purchase of a supplier or a distributor, can kick-start this growth. You are decreasing your transaction costs.

- Expand to New Products or Markets: This is the most complex growth change.

The Maturity Stage

Also known as the market maturity stage, this stage occurs when the rates of your sales begin to stabilize. Much of your customer base owns your product, but your profit margins are down. You still have high volume, but development and promotion spending are low. Your company’s goal is to maintain your market share. This is the most competitive time for your product. Related products in the marketplace become differentiated, and price wars and sales promotions are commonplace. At this stage, you need to choose your marketing campaign with the utmost care, as well as any product improvements. Product examples in the maturity stage are desktop and laptop computers. Companies can market the current set of diversified features to diverse segments of the marketplace, and there are multiple products available at different price points. For the marketing mix, focus on:

- Enhancing your product features to set it apart from the competition

- Decreasing your price

- Distributing more widely and offering incentives to companies carrying your product

- Focusing your promotion on your product’s differences

The following are strategies for companies to prolong the maturity stage for their product:

- Developing new uses for the product

- Developing reusable packaging

- Developing new markets at different price points

- Creating clear differentiation of your product from its competitors

- Emphasizing the brand image

The Decline Stage

Also known as the market decline stage, the saturation stage, or the abandonment stage, this is when your sales drop. Your product is either no longer relevant in the marketplace, your consumers have changed, or all of your customers have already purchased and will not do so again. Some of your competition may withdraw from the marketplace, and what is left may still be engaged in price wars. Production cost control is critical at this stage, and switching to cheaper markets may be reasonable. An example of a product in the decline stage is a typewriter. Although you can still purchase a typewriter and the accessories to support its functionality, there are no new radical developments or features coming. For the marketing mix, you want to focus on:

- Maintaining your product, but considering new features or ways to use it

- Reducing your production costs

- Discontinuing your product, or selling out to another firm that is willing to sunset the product

Strategies that keep your product from having a fast decline include:

- Adopting a selective distribution

- Introducing economy packs

- Adding in new features

- Making the packaging more attractive

Product Life Cycle Model Limitations

As previously mentioned, it is challenging to determine where a product is in the PLC. Sales are the main indicator, but the figures are calculated with some lag. Therefore, you only realize in retrospect when a product enters a new stage of the PLC. Further, a rise or a fall in sales may not signify a change in life cycle stage. The shape of the PLC curve on the graph is different for each product, and may only be used as a rough guide for marketing management and sales decisions. For example, the curve on the PLC for fashion products are usually quite steep in the growth stage, with a short maturity stage, and a steep slope in the decline stage. However, Levi’s jeans are an exception in fashion: the jeans have had a markedly long maturity stage. Also, the clear majority of products go directly from the introduction stage to the decline stage because they were never accepted in the marketplace.

Companies must be aware that making assumptions based solely on the PLC may be a costly mistake. Many companies focus more on new product development, erroneously believing that their product is in the decline stage. However, that product may still have untapped markets, uses, and users.

The PLC is an important planning tool, however. Experts recommend that instead of merely reacting to the trends in the marketplace, companies should use the PLC as a proactive strategy for their products, and plan for the various stages prior to the product launch.

Lastly, there are some differences inherent in the PLC when you cross national borders. The competition in domestic versus foreign markets may differ. Your product might be in the decline stage in the domestic market, while simultaneously in the growth stage internationally. However, most experts say that the product half-life in international markets is much shorter because the competition is so high.

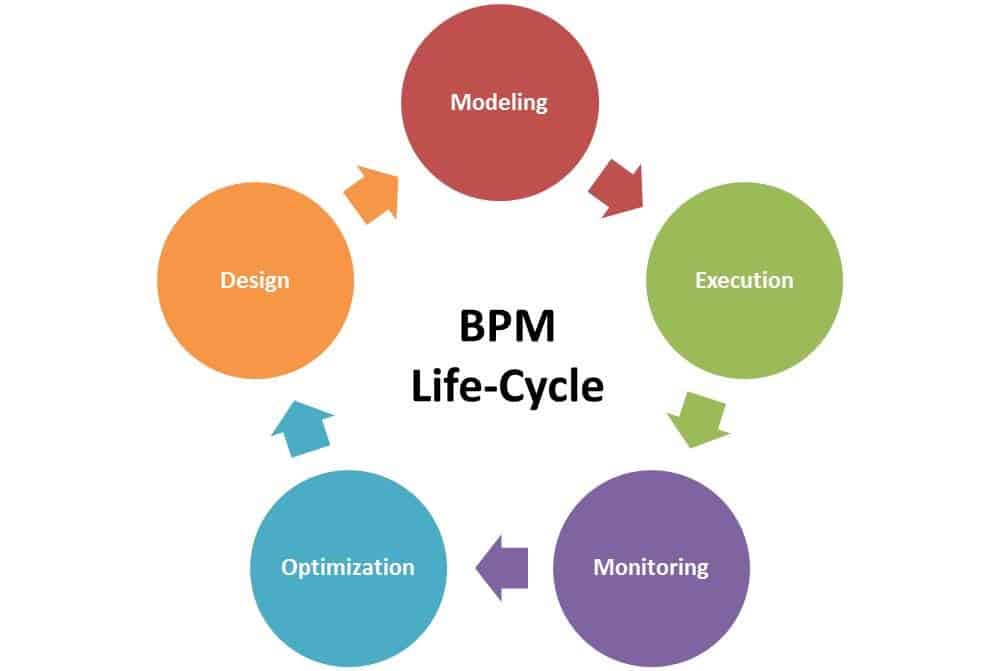

What Is the Process Life Cycle and Product-Process Matrix?

The process lifecycle, also known as the business process management (BPM) life cycle, is when a business examines the processes they use through the lens of continuous improvement. Each time you review your process or group of processes, you make improvements. This is good practice in BPM. The steps in the business process management (BPM) lifecycle are:

- Design

- Modeling

- Execution

- Monitoring

- Optimization

In BPM, you gather information about your process in the first step of design: define the steps, who participates, where the process starts and ends, and the overall purpose. Next, in the modeling phase, you create a diagram or a workflow in order to visualize the process as a whole. At execution, you start checking for opportunities for improvement and any weaknesses. In your monitoring phase, you are continuing the checking process since you now understand the entire process. During this phase, you can also test some scenarios to identify limitations of your process. Finally, you are stripping or adjusting your process in the optimization phase.

Credited to: Mariska Netjes, Halo A. Reijers, Wil M.P. van der Aalst.

For more information on BPM see, All about Business Process Management, with Expert Insights.

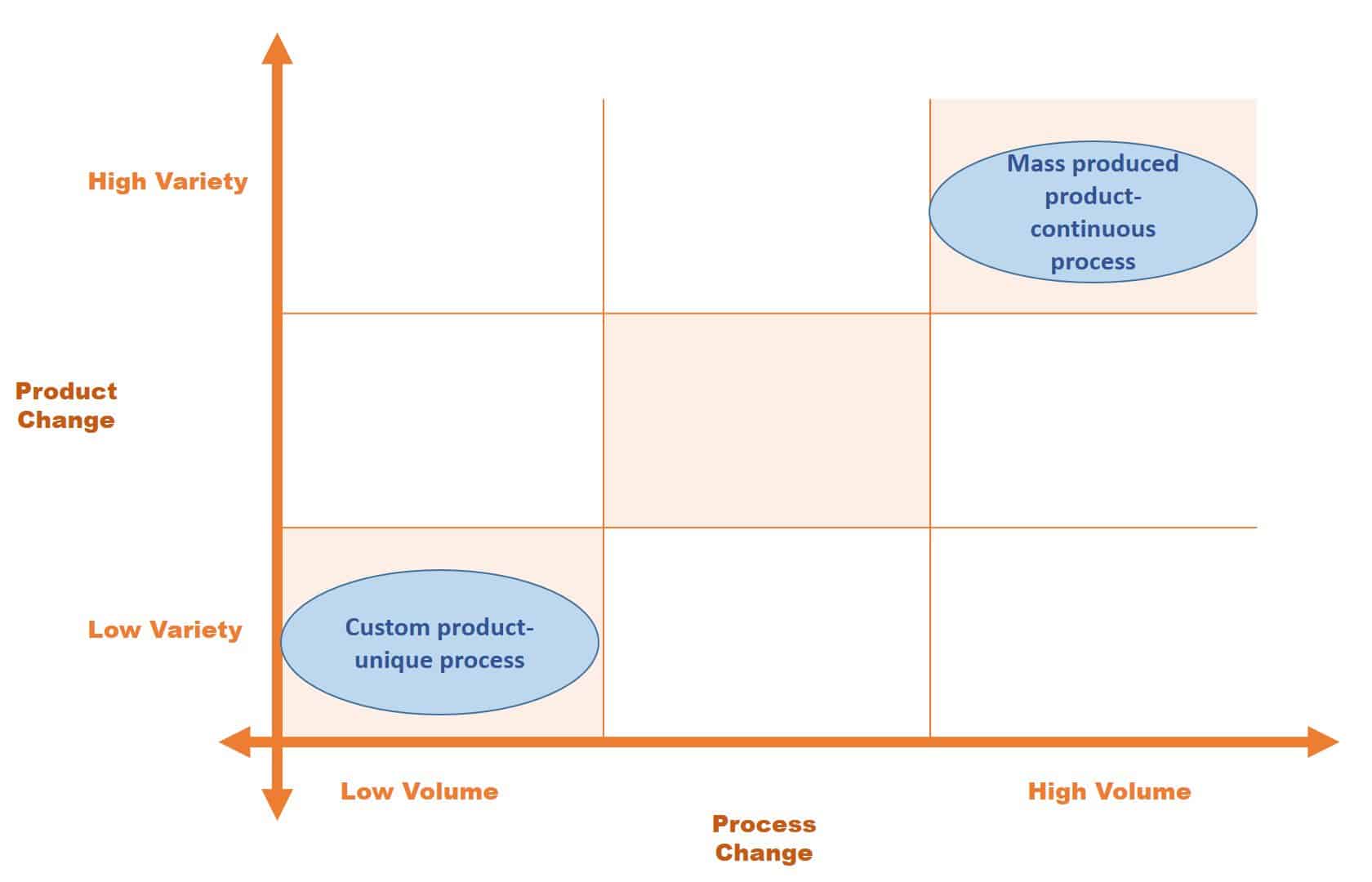

The Product-Process Matrix

When you combine the PLC and the BPM life cycle, you have a tool to analyze their relationship called the product-process matrix (PPM). It is logical that there is a link between the evolution of the product through its life cycle and evolution of the product’s manufacturing process. This matrix matches the stages of the product life cycle and the process life cycle and helps you determine whether your strategies are in your company’s area of expertise. In other words, if what you are doing or producing is an appropriate fit for your business. Further, this matrix shows the trade-offs your company may need to make in marketing and operations.

The original developers of the PPM postulated that there is a natural match in the middle of the matrix on the diagonal between the product change and the process change and that most manufacturing falls in the middle swath (most companies only stay in a small range in that swath). As companies move outside of the middle swath, they become atypical for their industry. However, experts note that it is possible for companies to be successful outside of that swath on the product-process matrix, but they must adapt their business strategy based on whether they are above or below the diagonal. Those above the diagonal should focus on marketing, service, or innovation. Those below the diagonal should focus on manufacturing.

This two-dimensional PPM point of view allows your company to understand what sets it apart from its competitors. This is called distinctive competence, and answers what your company does really well. Further, companies should guard distinctive competence from internal indecisiveness and external attack as they lead to your competitive advantage in the marketplace.

The implications of your company’s position on the PPM are telling. Companies who choose to focus on the upper left portion of the matrix need management that is capable of deciding when to abandon products. This contrasts with companies who focus on the lower right of the matrix - they need managers who can decide when to enter the market. The latter type of company does not need to be as flexible as the former type since they can keep an eye on how the market is developing and decide the best time to jump in.

Companies that want to change their position on the matrix need to be aware that a change in one dimension necessitates a corresponding change in the other dimension. For example, if a company wants to increase variety in their product (for example, adding a new flavor of toothpaste that they produce), they must also revisit their processes and add an additional process. In the processing dimension, simply adding or eliminating processes without a corresponding change in products can open a company up to an imbalance as well. Companies often try to respond to a market shift by improving their processes. This does make changes in the company, but it does not address the issue and pushes the organization out of balance on the PPM. This highlights the reason why companies must closely link marketing and manufacturing.

PPM can also highlight the loss of focus in a company. Marketing often wants to try new products or variation on products. However, if the processes needed to produce these products are too complex or numerous for your company, then these products may not be within your company’s focus area. This mismatch in the PPM of product change and process change highlights a loss of focus.

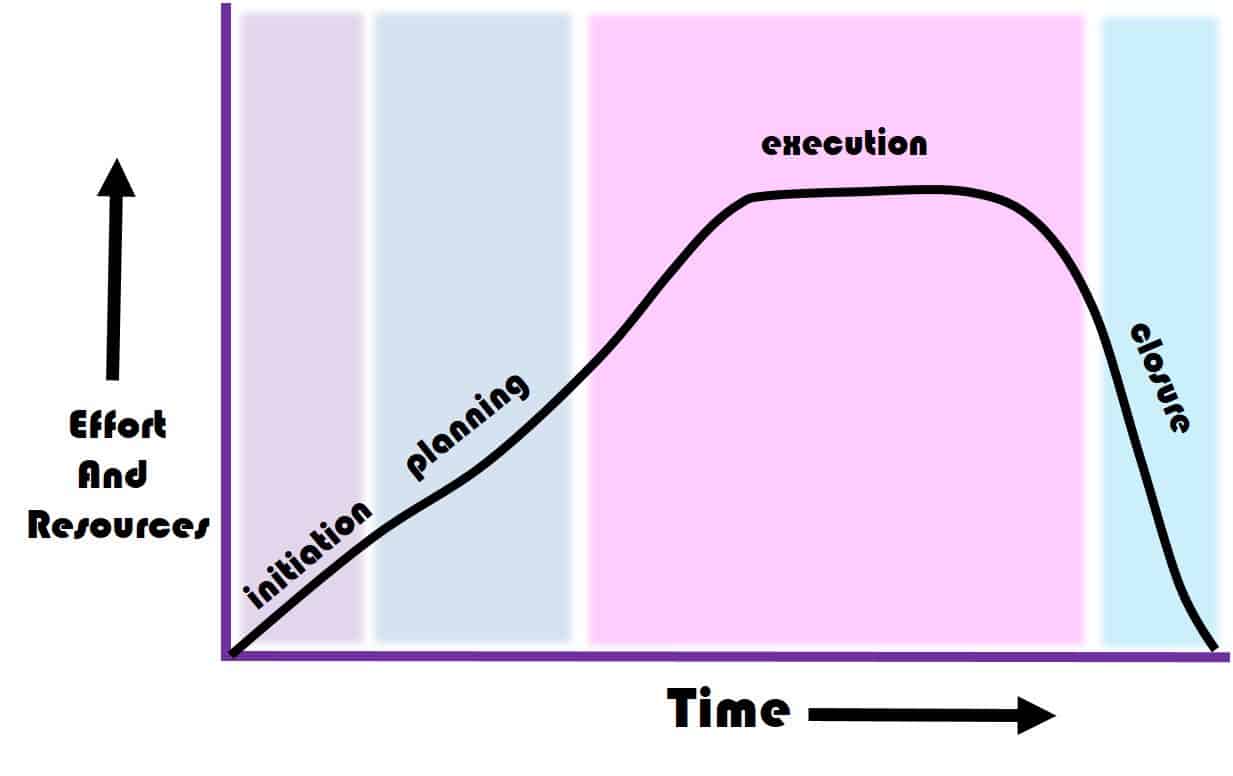

What Is the Project Life Cycle?

You can map a project of any size to the project life cycle. The project life cycle is included in this article because it goes hand-in-hand with the product life cycle. For example, you undertake a project to produce your product. Once you produce the product, your project is complete. A project is understood as having a definite beginning and a definite end. By contrast, a product life cycle may not have an end. Here are some additional differences between a product life cycle and a project life cycle:

- A product life cycle can include multiple projects.

- A product life cycle can be conceptual, while a project life cycle is specific and defined.

- A product life cycle does not have overlapping stages. A project life cycle may have overlapping stages.

- A project life cycle may have stages that repeat. A product life cycle will not have repeating stages.

In project management, the project lifecycle includes the stages and tasks that you go through to complete a project. A project has the goal of delivering the project objectives. Although every organization has a slightly different life cycle when you break it down into the required steps, all projects also go through the following four stages: initiation, planning, execution, and closure. The amount of work and resources that you put in are a function of where you are in your project stages.

The longest and most resource-intensive is the execution stage. However, it’s important to stress that you should take proper care in each of the other stages. In fact, you can break down each of the stages into their component steps. Project review forms may be completed (if your organization requires them) at the end of every stage.

Initiation: In this stage, you are starting your project. Depending on your organization, the steps you take may include identifying stakeholders, submitting a project request, developing a business case, performing a feasibility study, gathering your project team, researching your solutions, developing a project charter, and identifying your resources.

Planning: In this stage, you are organizing and preparing your project work. You should work out all the details of your project. If you did not complete a project charter in the last stage, complete it now. You should also complete a roles and responsibility charts (RACI), an issues log, a risk matrix, a resource plan, a communications plan, a training plan, a schedule, a budget, a quality plan, a procurement plan, and a contract with your suppliers. You should also have your full schedule and define your milestones and deliverables. Upon leaving this stage, there should be no unanswered questions about your project, and no surprises later on.

Execution: This is the stage where you get your work done. It is the longest and most resource-intensive stage, of course, but if you have performed your prior stages appropriately, minimal issues should occur. As a project manager, you have the responsibility of dealing with the everyday problems, but your planning should go a long way towards minimizing them. In this stage, you are building the deliverables, and also monitoring and controlling the work. During this stage, you are performing the tasks of all the plans you developed in the earlier stages, and creating status reports for your stakeholders. Should you require it, you are also handling the change management.

Closure: During this stage, the work required on your project plummets as you complete the project. However, professionals understand that this is a stage because it is just as important as all the others to close out a project properly. During this stage, you will complete all the project closure requirements, including creating lessons learned, archiving your project and all documents, and creating a post-project review.

What Is the History of the Product Life Cycle?

The theory of PLC was developed by Raymond Vernon in 1966. He also called it the International Product Life Cycle, and it is what we know and use still today. However, there were a few precursors to this life cycle. Notably, this was Otto Kleppner’s theory in 1931, and from Jones of Booz, Allen, and Hamilton’s life cycle in 1957. Otto Kleppner said that products go through three stages: pioneering, competitive, and retentive. Jones’ theory was more fleshed out and is a closer reflection of what we know today as the product life cycle; it includes introduction, growth, maturity, saturation, and decline. What is consistent in these theories is that profits are high when you are in a growth stage, and competition causes decline during your maturity stage.

PLC was mostly theoretical until 1985, when American Motors Corporation used the modern PLC and computer-aided design (CAD) to improve their product development process for their Jeep Grand Cherokee. This process that they developed with the PLC was extremely successful and is what we use today for product life cycle management (PLM).

How to Exploit the Product Life Cycle

You must first understand that products have a limited life and that all products will go through the PLC. Regardless of their seeming popularity and “classic” status, no product remains constant in a phase forever. For example, Levi’s jeans are a staple in fashion, have been in the maturity stage for an exceptionally long time. But in reality, the produce has also gone through many changes. Originally, due to the copper rivets holding them together, they were less apt to wear and tear. First made for working cowboys in the American west, they became more “fashionable” in the 1930s during a dude ranch craze on the East coast. Already by then, the demand for the jeans reached new markets. Today, this supposed “staple” has had hundreds of iterations and is in every fashion market segment from working clothes to high fashion.

Therefore, when a product enters a new stage of the PLC, there are new opportunities for it. For example, when you achieve the growth stage, you can optimize your processes for producing your product, as well as opportunities to add features that were left out of your product’s first iteration. When you reach the maturity stage, you have new opportunities to branch out into other markets and market segments.

There are three operating questions that managers should ask of each new product or service:

- What do we expect for the length and shape of each of the stages in the PLC?

- How do we know when it goes into a new stage?

- How can we capitalize on each stage?

Even though it is impossible to know the life cycle of every new product in advance, there is some planning that you can do. There is no universal slope and length of time on the PLC for a product; rather, the slope and length is dependent on the product’s complexity, how new it is in the marketplace, how it solves the customer’s problems, and its competition. However, before you launch a new product you can use the PLC to determine for each stage the actions your company can take, and how to best invest your capital.

In general, if your product is quite new to the marketplace, it will be in the introduction stage longer. This is because customer education happens slowly. There are always early adopters, but the mainstream customer takes time to decide if a new product will meet their needs. Entrepreneurs with highly innovative products may find this time lag frustrating, and the lack of capital in this stage contributes to the high product failure rate. But the aforementioned product complexity and level of innovation are not the only things that can increase the introduction stage and the risk of failure. Other factors include:

- How much does fashion influence the product? Products that are fashion-related have shorter PLCs. They move faster out of the introduction stage and faster into the decline stage.

- How many people must help decide to buy or not buy the product? If your product or service must go through many departments before a sale, your introduction time increases exponentially. For example, if you are selling an expensive software system for human resources, you may have to start with the company’s CEO, and go through the whole management team, the IT department, and the finance section before you even get to the human resources department (the users of the software). Each department or person that must sign off on the software adds time and costs your company money in the introduction stage.

- How big the shift is for the customer’s way of doing things? Since teaching many people to change their behavior takes time, even the most effective products may not be successful right away. For example, if you developed a product that changed the way people clean their teeth, not all people would be comfortable adopting it - at least not right away - because brushing teeth issomething they’ve done something their whole lives. Changing behavior takes time.

- How costly the product or service? Even early adopters with disposable income slow down if the price tag is too high. The higher the price, the slower most people choose to adopt the product.

However, with these increases in the introduction stage and in the risk of failure you have some other opportunities. These include:

- New products are automatically interesting. Even though you have a proportion of people waiting and watching to see the success of the product with the early adopters, there is still a mystique around the newness of a product, and a certain fashion that is attractive. This means, however, that your early publicity must be favorable.

- Choosing distributors who can teach the public about the best use of the product.This goes hand in hand with your favorable publicity. If you have distributors that lead the public the way you want, you do not have to invest so heavily in your next stage.

- You can set your prices higher. Even though a lower price may speed you through the introduction stage, it may shorten your life cycle overall. Your overall profits may be higher if the stages are longer.

Once a company proves that their product has a market and that demand does exist, competition arrives. Even though the product’s originator took on the brunt of the cost, pain, and risk of developing the item and the market, they are now faced with competition that can draw the market away from them. Further, that competition may be able to offer a better product with new features and at a lower price. This causes a squeeze in profits to the originator’s company, even if the market for that product is still viable and the industry is still selling the product well. However, looking at the PLC you see that this growth stage causes the need for increasing sales volume and lowering production costs. Overall profits increase.

In trying to recognize what stage your product is in, industry experts advise to look to the next stage first. Since we know the past and the present, we can only guess where our products may be in the future and what we can do to get there. If we plan for the next stage now, we can figure out how we will get there from today. This is the only thing that makes sense in trying to stretch your stages. In other words, plan early.

To expand your PLC, there are a few things that your company can do. These include:

- Increasing your current users’ use by promotion

- Increasing the functionality of the product for the current users

- Expanding the market by creating new users

- Finding new uses for the materials or components of the product

These strategies can extend your products in the marketplace. Especially when planned in advance, they give your company a chance to be active (instead of reactive) and the optimum time to infuse life into your product. Additionally, it makes your company look at your products from all angles.

Especially in this day and age of dramatically shrinking PLCs, finding ways to increase your competitiveness is critical. Some other ideas that may help to increase your overall PLC are:

- Introduce technology that can help you manage operational changes.

- Develop forecasts to keep you informed of the demand, customer buying patterns, and other market signals that can tell you when and how to adjust your supply.

- Optimize your supply chain.

- Adapt to the new PLC markets; commit to competing in this new world.

The Future of the Product Lifecycle

According to experts, the future of PLC is based on the need for manufacturers to evolve. Because of technology, innovation, advanced performance, and customization, customer expectations are also evolving. Manufacturers must learn to be adaptable so that they do not allow the speed of demand to become a roadblock to their success. Some of the recommendations from industry experts include:

- Look at your product development holistically using modern technology such as 3D printing for prototypes and configure-price-quote (CPQ) tools.

- Keep on top of your suppliers, requiring them to be reactive to the changing customer needs.

- Use customization to your company’s benefit. Products that can interchange offer the level of customization that customers expect while keeping the cost of manufacturing and inventory storage down.

- Consider other new technologies for your product tracking, such as using the Internet of Things (IoT) to tell you how well your products are holding up, how they are being used, and how they are performing.

We queried some experts to get their input on the current and future state of PLC. They were also happy to give advice to other both new and experienced professionals.

“The current landscape of product life cycle typically has four phases: New product introductions, growth, maturity, and retirement. New products go through the excitement of inception, planning, and launching. At the same time, it has the challenge of getting new customers, hitting revenue targets, and capturing market share. Growth is focused on capturing the market share and seeing profitability. Maturity stage focuses on service agreements and retaining existing customers. As the market matures there comes a point when newer products using the latest technologies force an existing product’s retirement. Case in point was the dwindling demand for SunGard’s disaster recovery solutions with the advent of cloud solutions (which has inbuilt disaster recovery).

“The future of product life cycle is based on the fail quick mantra. New products have to be introduced very quickly to beat competition. With the use of disruptive technology tools, it is easy to get ahead of the curve of your product lifecycle. For example, a tool like Salesforce Einstein can be utilized to come up with scalable business models. Incorporating viral marketing techniques is imperative to accelerate your growth. The rising use of the Internet of Things can help with proactive maintenance of the systems during the maturity phase.

We will also notice shorter product lifecycles as competitors, creative entrepreneurs, and emerging technology startups disrupt existing markets faster than ever.

“My advice for other product management professionals would be: Don’t wait for the perfect product. As long as the core functionality of solving a customer problem is met, release the product to the market. If the market validation is not successful, pivot the core functionality of the product or move on to a different one. Ensure that you stay on top of the emerging technology trends not only for new products, but also for enhancing existing products. And lastly, focusing on the customers instead of the product will ensure its success.”

“From the user perspective, the Army had a problem. It had to figure out how to restore the useful life of Army equipment. In 2005, the Army initiated equipment Reset. The Army’s Reset program’s focus was to reverse the stress of intense combat operations and restore the life cycle of its equipment. The Army’s usage rate was six times greater than peacetime planning factors and Reset was the mechanism to provide the U.S. Army the equipment, vehicles, helicopters, and tanks to continue the long-term fight against terrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan. This forced us to continuously buy new equipment and put stress on the manufacturers and the whole supply chain. Manufacturers cannot spend time updating their equipment and developing new features when they have products that are wearing out too quickly for them to replace, and we needed those products.

“Specifically, for Army Aviation, upon returning from theater, all redeploying aircraft were either sent to designated facilities within the United States or to Reset sites at home station. During Reset the aircraft would undergo a complete replacing of all damaged parts, recapitalization to refurbish equipment, or repair to return aircraft to correct Army standards. The U.S. Army Aviation managed this process and Missile Command (AMCOM) based out of Redstone Arsenal, AL. Specifically, AMCOM Logistic Center (ALC) provided direct oversight, contracting, and management of the Army’s Aviation Reset program. The Reset program allowed the U.S. Army to restore and manage its equipment life cycle resulting in a combat-ready fleet for our history’s longest war and resulting in a longer product life cycle.

“I would advise other professionals in PLC to consider the intended life of the product that you put out there, whether for just regular use or in extreme use, and what that could do to your product life cycle with respect to your processes, development, and customer supply needs.”

More Information on the Product Life Cycle

For more information on PLC, read these recommended books:

-

The Product Manager's Handbook: The Complete Product Management Resource, 2nd Edition, by Linda Gorchels

-

Product Lifecycle Management (Volume 1): 21st Century Paradigm for Product Realisation, (Decision Engineering) 3rd ed. 2015 Edition, by John Stark

-

Operations Management for Dummies, by Mary Ann Anderson, Edward J. Anderson, and Geoffrey Parker

Efficiently Manage and Monitor the Product Life Cycle with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.