What Is a Failed Project?

First, let’s define a project. According to the Project Management Institute (PMI), a project is temporary, with a defined beginning, end, scope, and resources. It is unique and works toward a singular goal. Projects often include people who do not regularly work together.

The discipline of project management concerns the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques for the purpose of meeting the requirements of a project. Organizations have long practiced project management, but it became a profession in the mid-20th century. Today, there are several certifications for project managers.

Every organization has a different definition of what constitutes a project failure. Often, it means a project is over budget, over deadline, or over schedule. It can also mean it did not satisfy stakeholders. Of course, a failure can consist of any combination of these reasons.

A failed project can be demoralizing for the people who worked on it, especially if they did not see it coming.

What Are the Main Causes of Project Failure?

It is often difficult to pinpoint why a project fails. Sometimes, there is a trigger event, but failure usually happens after many problems surface. The main causes of project failure are inadequate planning, insufficient resources, and deficient leadership and governance.

When arriving on the scene, Williams needs to do a quick assessment, and he likens this process to dealing with a big case that’s coming into an emergency room. To extend the metaphor, there is usually a lot of blood, and the first step is to stop the bleeding. Then, you figure out what to do next. He uses a similar process for projects, controlling the obvious problems and then looking for what caused them.

As mentioned above, there are three main root causes of project failure: inadequate planning, insufficient resources, and deficient leadership and governance.

-

Planning:

-

A lack of definition for the goal and the vision

-

Inaccurate estimates regarding time, money, etc.

-

Inadequate risk management

-

-

Resources:

-

Team issues, including interpersonal problems

-

A lack of money

-

A lack of time

-

-

Leadership and Governance:

-

Decision-making problems

-

An insufficient understanding of stakeholders and their expectations

-

Poor project tracking and communication

-

“Most people feel that when projects go bad, it’s because there was something inherently wrong with the project or the team. In the majority of projects, however, it’s a case of the executives not knowing what they’re doing from a project management perspective,” Williams says. He notes that executives often do not have project management experience and do not understand everything that goes into completing a project.

Project Failure due to Poor Planning

Planning is what happens before work on a project begins and is often where projects begin to fail. Sometimes, it isn’t clear until later in the project that it was a planning error that caused the failure.

When beginning a project, many managers keep a triangle in mind. PMI refers to this concept as the iron triangle.

The iron triangle highlights the constraints of project management that impact quality: scope, time, and cost. When a project begins, a manager tries to keep the triangle as equilateral as possible. As a project progresses, changes in one constraint impact the others, and it is up to the manager to make trades between constraints. “Something needs to give,” Balaban says.

One big problem with planning often involves the scope of the project. Scope has a way of changing or creeping, and when it does, it often means more money, time, and people. Unclear goals, objectives, and deliverables can lead to scope changes. The project can also be too complex or too oversimplified to fit into its initial scope.

Williams says organizations often use the term “scope creep” inaccurately when talking about changes in scope. He explains that, by definition, scope creep is uncontrolled change to a project. For example, if someone puts in a change order and the scope officially changes, then that’s not considered scope creep, since the change is controlled.

Along with the changes in scope, bad estimates about time and resources can cause problems for project managers. Metaphorically speaking, sometimes an organization’s eyes can be bigger than its stomach, resulting in a project that’s too big for the team, the time, and the resources available. Inaccurately estimating the time necessary for a project leads first to the unrealistic commitment of time and people, and ultimately, to project failure.

Williams says, “It is all unknown. [Projects involve] moving something into a new area, and there will always be something that comes up.” He relates a project to putting up holiday decorations and lights: “You think you know how long it will take, and you test the lights on the ground to make sure they work. Then, when you get them on the roof, they don’t work for some unknown reason. Your next job is to figure out why they aren’t working, so you can fix the problem.”

Differing expectations can also lead to project failure. Project planners sometimes have different views about the quality and standards a project should have. When these contradictory views compete, the schedule and the budget can take priority over quality, practically guaranteeing the defeat of a project.

Planning for the worst and hoping for the best is part of a project’s risk management. Problems and setbacks are inevitable in almost any project, and neglecting to plan for them can cause a project to fail. It is impossible to predict everything that could possibly happen, which is why it is crucial to have a contingency plan in place in case some parts of the project take extra time or cost more than originally planned.

“Regardless of the project, there is always something that comes along. If you don’t take an adaptive approach to a project, it will, in most cases, simply get progressively worse,” Williams says.

Project Failure Due to Inadequate Resources

Poor planning is one key reason projects fail, but issues with resources can also lead to failed projects.

Picking the wrong people or not having enough people to work on a project can lead to failure. Finding warm bodies to put on a project instead of waiting for the correct personnel can mean people lack the expertise they need to do the job. Involving the client in the process of selecting qualified staff can help you avoid a gap in proficiency.

Because projects often involve people who do not usually work together, team issues frequently arise. Projects can fail because of something a team did poorly or failed to do, and interpersonal issues and friction can put a team in turmoil.

Coordination and communication — both among team members and from project leaders — can be a deciding factor between success and failure. Leaders often do not clarify roles and responsibilities for individual team members, which leads to confusion.

“There are numerous interpersonal issues on any failed project. Sometimes, people are talking to one another, and they think they are saying the same thing, but they’re not,” says Williams. Project managers think in terms of scope, schedule, and budget, while executives think about value and the bottom line. The terminology can differ greatly.

When a team member doesn’t understand why something has to be done in a certain way, it can lead to uncertainty and a lack of buy-in on a project. In turn, these sentiments can translate into an absence of accountability and a poor attitude.

Training is vital. Getting everyone who is involved in the project to understand the skills they will need is necessary for the project to be successful. When looking at training requirements, project managers often overlook the potential for technology problems or the need for task-specific equipment. When you don’t test technology properly, address feedback about tech issues, or provide training, you’re courting project failure.

Unrealistic estimates regarding both budgets and personnel can also cause failures. Planners often cut the former and the latter to make a project seem more attractive to either management or a client. Not allocating enough time to complete a project is another way to end up with shoddy work.

In addition, there is the case of what Hofmeyer calls “passive resistance:” “People don’t believe in the task they’re doing, so they go through the motions and sometimes don’t even perform the task.” This type of person is the opposite of the critical thinker who grasps the bigger picture of a project.

Recognizing and understanding each team member’s style can help get a project off the ground. Hofmeyer suggests having a senior leader kick off a project by conceding that leadership does not have all of the answers — this approach encourages critical thinking and discourages passive resistance among team members.

Hofmeyer also recommends keeping an eye on cultural differences within project groups. For instance, some people are brought up to always say yes and be positive, even when things are not going well. They will not speak up to raise a red flag.

Project Failure due to Leadership and Governance

In addition to projects failing because of planning and resources, they also fail because of poor leadership and governance.

“We’re in a world of ‘yes’ people. It hurts to say no, and it’s killing us. Things slow down because everyone wants to say yes,” Williams says. Because of this phenomenon, new items become part of the scope, teams do not have enough time, budget overruns occur, and projects fail.

Poor leadership does not necessarily indicate you have a poor project manager — it can also be an indication of an unsupported project culture, bad executive leadership, or an absence of consensus among stakeholders. Lack of client involvement in decision making can also be fatal for projects.

For instance, an executive’s pet project is often doomed to fail from the beginning, because it usually originates from a place without logic — i.e., the executive does not consider how the concept fits into the company’s overall objectives or goals. In this situation, the idea generally doesn’t even make it past the vetting stage.

Poor leadership and poor communication often go hand in hand. If team members do not have a clear idea of their role or responsibilities, the project can fail. Timely feedback is also important.

“I sometimes err on the side of over-communication. You get that moment when someone says, ‘Oh, I didn’t realize,’ and, at that time, you can fix it,” says Balaban.

Sometimes, project managers lack the necessary skills for a particular project or fail to do the following:

-

Update the schedule.

-

Create enough checkpoints and milestones.

-

Monitor or control what is happening with their team.

Project managers can also make a project more complex than it needs to be. Breaking down tasks into smaller pieces can help keep a project on track. If a manager does not explain how some tasks are interdependent (i.e., that certain tasks cannot begin if others are not completed, etc.), then team members will not understand that someone is waiting on something they’re doing. In this way, the project will fail.

However, the planning can go too far. Hofmeyer explains that project managers often over-architect a project, planning too far ahead and forcing the interrelatedness of even the smallest tasks. “Only project plan to the point needed on each group’s level,” he suggests. Then, individuals and teams can track smaller tasks on their own levels.

Why Some Failing Projects Continue

On occasion, even projects that illustrate the most spectacular signs of failure continue. This can happen for reasons as simple as not paying attention to warning signs or choosing to ignore them.

Often, an organization will stick with a failing project if it has already invested a lot of time and money in it. Proceeding with this mindset, decision makers labor under the delusion that stopping the project at this point will only waste the money that has already been spent or indicate an admission of defeat.

“I think most of it is pride and an inability to make decisions. People don’t want to admit this is harder than they thought,” Williams says. At other times, one is faced with a situation in which a project must continue. Williams uses the example of remodeling the front of his house. While doing the work, a water line to the house broke. Even though replacing the water line was not included in the original scope of work or within the original budget, there was a huge, muddy hole in the front yard, so, therefore, the water line had to be replaced.

In some cases, the individual pieces of a project are complete, but they just don’t work together. Leadership will often keep a project going in the hopes of salvaging it.

Famous Failed Projects

Some projects start out as great ideas, but fail miserably. Others seem doomed from the start. Even successful companies have failures.

| Project Name | Intent | What Failed |

|---|---|---|

| Boston Big Dig Construction Project | The ambitious project began in the 1970s and finally ended in 2005. It was a huge urban infrastructure project to bury and expand highways. | Cost and time overruns plagued the project. Several accidents, including a tunnel collapse and leaks, also caused trouble. When it was finally finished, it had spanned six U.S. presidents, and the project had accrued multiple billions of dollars in cost overrun. |

| Denver International Airport Baggage System | By automating baggage handling throughout the airport, it was supposed to be the most advanced baggage- handling system in the world. | Problems with it were so severe that the new airport sat idle for 16 months while engineers tried to fix the baggage system. When finally implemented, the system did only a part of what it was designed to do, and that part never functioned properly and was finally abandoned. |

| British National Health System Civilian IT Project | The British government wanted to create the world’s largest patient record system. | When it began in 2002, the system was supposed to integrate patient health records from the top down. Neither doctors nor patients trusted it. It was dismantled in 2011. |

| Sony Betamax | In the 1970s, the Betamax was supposed to revolutionize the video recording industry. | Betamax hit the market at the same time as JVC’s VHS technology, the latter being cheaper and non-proprietary. |

| New Coke | Introduced in 1985, New Coke was marketed as a better tasting Coke. | Coca-Cola was losing ground to Pepsi, so Coke tried to make a product that tasted more like Pepsi. The testing sample size was not very large. Coca-Cola abandoned production after only a few weeks and went back to its original formula, naming it Coca-Cola Classic. |

| Polaroid Instant Home Movies | This product allowed people to record video and watch it in a matter of minutes. | The product lasted only two years because the videos had a time limit and no sound. Moreover, one could not view the videos on a regular television. |

| Crystal Pepsi | Crystal Pepsi was supposed to be a new and novel version of an old favorite. | Once the novelty wore off, customers stopped buying it. People complained about the flavor. |

| McDonald’s Arch Deluxe Burger | Introduced in 1996, it was supposed to be a sophisticated burger for suburbanites. | Even though McDonald’s spent at least $100 million advertising the product, it never caught on. |

| Apple Lisa | It was the first desktop computer that came with a mouse. | Apple over-promised and under-delivered a product that simply did not live up to consumer expectations. |

| Levi Type 1 Jeans | The jeans had rivets, stitches, and buttons that were exaggerated. | The company ran a Super Bowl ad and the style never caught on. Customers did not understand the point of the style. |

| IBM PCjr | In 1983, IBM released the project to attract home computer users. It was more expensive than its competitors and had fewer features. | The product was expensive and had a keyboard that got a lot of complaints from customers. IBM tried to fix the keyboard, but it was too late. |

| Ford Edsel | Unveiled in 1957, the Edsel was supposed to have a design that consumers had never seen before. Ford invested $400 million in the design and marketing of the car. | Ford’s research and production took too long — by the time the car came out, buyers were already beginning to look for smaller and more efficient cars. Production stopped in 1960. |

| Apple Newton | In 1993, the Newton was one of the first personal digital assistants on the market. | The price tag of $700 was too high, the device was too big, and the capabilities, including handwriting recognition, were not good. |

| Windows 8 | The Microsoft operating system with a new interface was supposed to make it easier for users to navigate their personal computers. | Windows 8 took away features that customers were used to, like the start menu. Adoption was slow. The company quickly came out with Windows 10. |

How to Recover a Failing Project

In this section, we’ll detail the phases and actions to take to recover a failing project.

Recognize a Failing Project

The first step to recover a failing project is to recognize it is failing. With most projects, there is a time when recovery is possible, but often that window of opportunity is short. There’s no need to panic, but sounding an alarm about a project’s problems is critical.

It is also important to resist the temptation to place blame for why a project is failing.

“Don’t panic. Go into it with a clear mind and then start doing some due diligence about what is going on with the project,” Balaban advises. “You have to change the way you have been doing something, or you’re never going to turn it around,” she adds.

Assess the Project Status

A proper evaluation of a project’s status is the way to figure out what a team’s next steps should be. Gather all the data you can about a project’s current status.

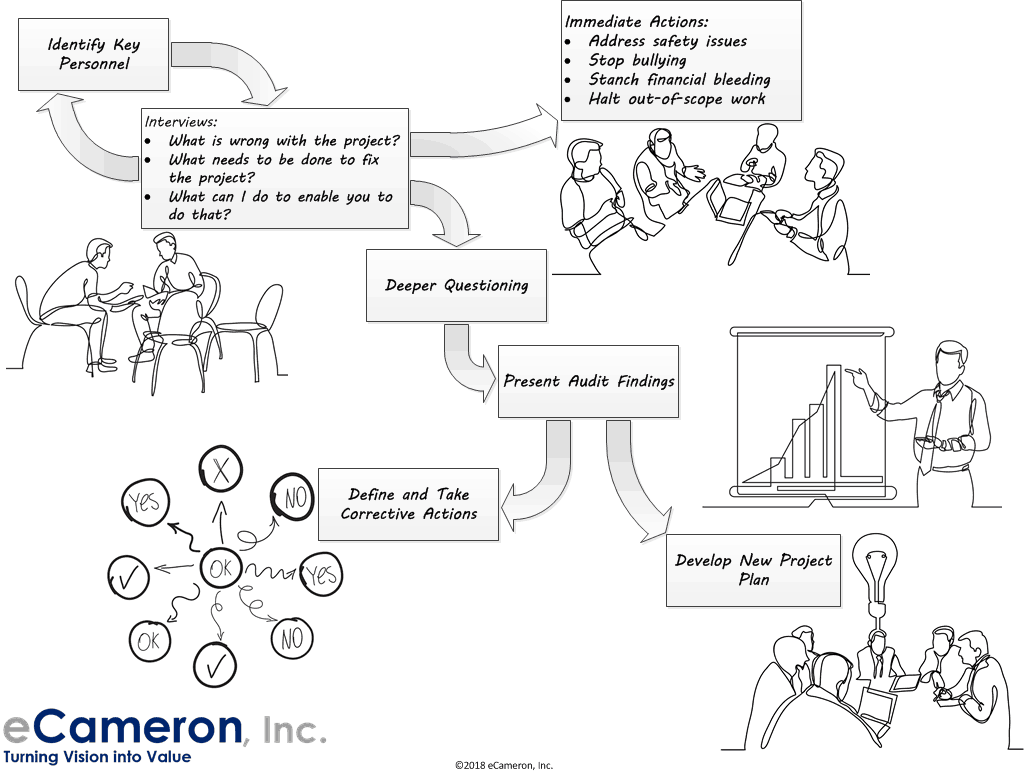

“One of the first things I do is interview people,” Williams says. His interview subjects include people who are at the nucleus of a project, from the project manager to customers, team leaders, and executive sponsors. Williams also interviews those he calls the “insignificant people,” as far as leadership of the project is concerned. These “insignificant people” are of course the ones who actually do the work, such as those on the manufacturing floor or a coder or tester.

“These are people who aren’t at the core of leadership, but have insight into a project that nobody else has,” Williams explains. These people often know what is really happening on a basic level. Maybe, something a manager thought would take two hours actually takes four. Or, maybe a computer is not powerful enough to do a job. Perhaps, people who are working on multiple projects simultaneously find that an altogether different project has taken priority. Interviews will help identify these causes.

Williams always asks the following three questions:

-

What is wrong with the project?

-

What needs to be done to fix the project?

-

What can I do to enable you to do that?

“All three of these questions are open ended and connote respect for and trust in the person I am interviewing, because they are about the person,” Williams emphasizes. “This has a number of positive outcomes. It builds trust, establishes confidence, prompts people to provide their personal thoughts, and starts the team-building process. All of these ingredients are necessary, as most people on trouble projects are taking a beating for the failures and are the focus of their blame. Asking additional questions will provide further detail,” he says.

Hofmeyer suggests interviewing people separately and then gathering them into a group to present your findings. “People in one-on-one situations have a very different understanding of a project,” he says. “If you get everyone in a group, you will have a few noisy people. Everyone else will be quiet. They won’t want to speak up,” he says.

Another step is to read all the documents concerning the project. This is a good time to remind yourself about the original scope, plans, charter, and specifications. Looking back at documentation can help you see what needs to happen going forward and can help you find the failure point.

After looking at the data, discuss recovery options with the stakeholders. Gather the current project team and include them in the recovery plans if it is appropriate to do so. Also, it might be a good idea to have a private discussion with the project manager regarding the project’s status. You take this step to make sure the project manager wants to be involved in any recovery. Remember that sometimes, a failure can be emotionally, mentally, and physically damaging.

Williams reminds managers to corroborate the various accounts of a project’s failure. “Having just one person say something means nothing,” he says, adding that the very person trying to pin a failure on someone else may well be the one who’s causing the problems. Getting multiple people to describe the same problem will pinpoint the common sources of that problem. “It doesn’t take a lot to start seeing those common threads and opinions,” Williams says.

Develop a Recovery Plan

When a project fails, the project recovery plan can help put it back on track. The nature and scope of the project will determine what goes into the plan, but most plans have some similarities:

-

An assessment of the current status

-

A look at the obstacles and problems facing the project

-

A plan for the recovery

-

A list of the responsibilities and the people in charge of them

You might assume that a recovery plan template would facilitate the recovery process, but that might not be the case. Williams, Balaban, and others do not recommend using them because they can oversimplify things. "I do have a very defined process, but as far as a plan, every recovery is different, so a [template] does not make sense in that respect," Williams explains. "While doing a recovery, you find out new things every day and need to move in new directions. In general, I audit and then take action, but that can change if I find something egregious," he adds.

Taking a look at the project leadership is an important step in your plan. Hiring a recovery project manager outside of the original leadership pool is one option, but it is not for everyone. In some cases, the existing project manager might be able to re-work the project, but this route is risky.

“The project manager is tainted and is too invested in the project,” Williams advises. He believes it is difficult to lead your own project’s recovery, since it is not human nature to call foul on yourself. “Sometimes, [project managers] don’t even know they are doing something wrong,” he says. An outsider can find it easier to gain the trust of the team and begin the recovery.

“When you have a failed project, nobody trusts anybody else, so the real key is to build trust and get somebody in charge that people can trust,” he adds. “Once people see you’re trying to work for them and not for yourself, they’ll begin to trust you,” he continues.

Building team morale and working out any personnel problems are two issues you need to address at the beginning of any project recovery. Doing so is a way to put the past behind you and work toward the future. The key is to move on.

“You never forget, but you should forgive. You have to remember that a failure occurred, and you have to remember why that failure occurred. Remember the signs that led to the failure, so you can come up with a solution,” says Williams.

Turning Around a Failing Project

When turning around a failing project, it is important to remember the three main areas in which project failure can occur: planning, resources, and leadership and governance. Addressing each one can help get things back on track.

Implementing good processes from the outset of a project reboot can help your team avoid a crisis-mode mentality. Considering all the alternatives and not just the first solution can make the overall goals seem clearer and more achievable.

After interviewing people involved in a project, Williams prepares an audit report containing different aspects of that project, including whether it’s going well, needs work, or is off track.

He suggests presenting the report in person and following up with a written form, because if people are in the same room together, they can make changes immediately. “People want things to be solved. Often, things can get fixed quickly, and that’s how recovery begins,” Williams says.

After any project, whether it be a success or a failure, it’s important to take note of what went smoothly as well as what could use improvement. Hofmeyer says it’s crucial to remember the lessons learned: “Most people have a particular work pattern, so they just forget about lessons learned and keep doing what they did before. It’s really hard to change people.”

Turning Around a Failing Project When the Problem Is Planning

The assessment of project documents should reveal the initial scope of a project. If the scope is too big, consider reducing it to match what the team can actually accomplish.

Reducing scope change and creep, focusing on the original scope, or finding a new scope can help get people on the same page, create a new vision, and set priorities. Have all the stakeholders sign off on the new scope of the project. Williams points out that during the recovery process, he can often remove much of the scope without changing the project’s value.

Identify the deliverables and break down work requirements. (Work breakdown structures help you break down the assignments and requirements into more manageable pieces.) Then, take a look at your new timeline as well as the resources available to you. Overestimate the duration of the project and how long tasks might take.

The new project schedule should include work requirements that you break down according to milestones and an outline of which tasks need to happen and when. A project evaluation and review technique (PERT) chart might help with estimating time and dependencies among tasks.

Additionally, quick wins can help re-energize the team and provide momentum as you push toward project recovery.

“It’s important to give people kudos. Sometimes, you focus only on the negative,” Hofmeyer says, adding that managers should make sure they are not overdoing it or faking praise. “It’s important to do it when it is deserved, but if you do it all the time, it won’t be respected or valued by the team.”

Mini projects along the way can fit into an overall plan and help provide a model for the bigger project. The Agile project management approach can help guide this process by breaking down large tasks into iterations. The project team reviews and critiques each iteration.

As a team, discuss how communication broke down earlier in the project and what everyone can do better this time around.

Project management software can help keep projects on track, but it has limitations. The software can be robust, but is only as good as the information people put into it.

“If a project is poorly managed, everything may appear to be green and on schedule [software-wise], until, at the last minute, just before something is due, the team realizes that the work will not get done,” Hofmeyer says. Some managers do not encourage or allow people to update tasks on their own, which can be a problem and can discourage team members from marking something with yellow or red to signify an arising issue. “I’d much rather have a project that has challenges that get addressed early on,” he emphasizes.

Testing projects along the way instead of at the very end can also be helpful in preventing future failures, especially if different teams are creating separate parts that need to work together. Finding out that something is not integrating properly while there is still time to correct a problem can save a project.

Turning Around a Failing Project When the Problem Is Resources

Projects often fail because they run out of money or the people working on the project simply can’t get everything done. Fixing problems with resources can help get a project back on track.

Getting the team involved from the beginning of a project reboot is a way to rebuild everyone’s confidence and regain focus. This is also the time to discuss any problems the team had up until this point in order to determine how to prevent the same situation from happening in the future. Sometimes, building up the team requires learning how to argue more efficiently — that is, homing in on project details rather than personalities.

“It’s really important to praise in public and criticize in private. You want to make sure there is an atmosphere of openness,” Hofmeyer says. Then, in a one-on-one context, you should address a team member’s personal issues, because they don’t just go away, Hofmeyer adds.

Creating a realistic and accurate schedule is essential. An eight-hour workday translates into only about six hours of actual work time, so keep that in mind when creating new timelines and schedules. Overestimating the amount of time available in a workday might be what got the project in trouble initially.

Hofmeyer says that on any project, 20 percent of the people do about 80 percent of the work, so he suggests that when re-tasking a project, you should make sure the work is more balanced.

Also, be aware of the other projects that each team member is working on. People may be working on multiple projects with similar deadlines, which could impact their availability. This factor is particularly important when trying to turn around a failing or overdue project. A project may have been unsuccessful precisely because team members were overcommitted and had to fulfill other responsibilities.

As a way of controlling team dynamics, make sure you clearly define any new roles and responsibilities. The project manager sets the tone for communication and needs to be clear in terms of delivery and expectations.

If communication breakdowns were part of why the project initially failed, centralizing all project communication in one visible location can keep team members informed. Everyone on the team should have access to this location. Set parameters for communication. Is email the best? Should one reply directly to the individual who sends an email or reply to the entire team?

Follow up on all methods of communication. Sometimes, people miss emails or accidentally delete them. Don’t assume people will remember something someone told them previously. Follow up.

“When you kick off a project, you should tell your team what your communication plan will be,” Balaban suggests. You should also include a plan for escalation, should a problem arise. “Everyone should know ahead of time how the plan will work,” she continues.

In kickoff meetings, Balaban says she always asks her team one question: “Is there anything I haven’t covered that I should?” Doing so fosters openness and demonstrates from the outset that you’re willing to listen and learn from the team.

Dealing with funders and key stakeholders is a separate issue. “Find out your stakeholders’ preferred form of communication,” Balaban says. She uses the example of one former boss who just wanted her to come into his office and informally tell him what was happening with the project she was running. Another wanted formal presentations with handouts and slides.

If the appropriate people were not part of the initial team, the recovery phase is the time to make those personnel changes. “If you receive the B or C team, you need to keep communicating with the leadership, telling them that the team is not delivering,” Balaban recommends.

Turning Around a Failing Project When the Problem Is Leadership and Governance

Sometimes, a leadership problem causes a project to fail. Managers may dread telling executive leadership that a project has failed or is failing, but it is ultimately the right move, because the C-suite needs to be involved in the recovery process. They are the ones who decide whether to keep the project manager on for the recovery or to assign someone else.

If you decide to bring on a new project manager, Williams suggests making sure that they are capable of pushing back against requests from executive leadership and are able to explain the recovery process that needs to occur. Not all leaders are cut out for all projects. Some teams need command and control leaders, while others need serving leaders. Leadership style can make a big difference.

“Project managers need to be able to lead their leaders. There’s no formula for it, but there is a process of taking the executive down the road of discovery,” Williams says. He advises showing leadership the corrective steps and changes you wish to take instead of presenting broad concepts. This illustrative approach can help leadership understand where the project might have initially gone off course. It can also help them see what needs to change now.

“[Executive leadership] needs to be open to the fact that their decision-making process can be wrong,” Williams explains.

If the current manager stays on, they need to retrace their steps and determine how the project arrived at this failing point. As integral members of the project, the team can assist with this process. The solution may be as simple as listening to all ideas and making people feel heard. Moreover, addressing poor team dynamics and underperforming team members is paramount to future success.

“As a project manager, you need to take responsibility. You need to ask yourself, ‘What did I do that I could have done better?’” Balaban advises. “Project managers are accountable for the project. It is their responsibility. If things are going wrong, it is your responsibility to raise your hand and say so.”

Once the project manager identifies the issues, they must take steps to repair them or the project will fail again.

Communication is key. Project managers can use checkpoints with their people to keep projects on track and understand what each person is doing to contribute.

Project managers should also do the following:

-

Communicate with the team clearly and often.

-

Check in with people regularly, without micromanaging.

-

Communicate with all stakeholders.

“You don’t start out by micromanaging. You let the results of the work effort drive your actions,” Hofmeyer recommends.

Empowering others to post updates to project management software and other locations can lessen some of the workload.

“If project management is taking up the majority of your time, then you don’t have time to get any actual work done,” Hofmeyer cautions. He recommends planning to a higher level and relying on individuals and teams to manage the tasks necessary to reach the milestones.

Following through on promises will help keep the project on track. “If you say we’re going to do better this time, but you do the same thing you did before, you will get the same negative result,” Hofmeyer says. He uses the example of promising to keep to a schedule of weekly meetings: No matter how short the standing meeting, you should continue to have it and use it for constructive purposes. Don’t just read the public status reports that your team members post to your project management tool.

Turning Around Different Types of Projects

Even though there are countless industries and kinds of projects, the process of turning around a failing project is similar no matter the type of project.

“It depends on your tolerance for failure,” Balaban explains. For example, a research and development firm might acknowledge that failure is part of discovery. On the other hand, a construction firm responsible for building a bridge is not too accepting of failure, which makes recovery more difficult.

Whether it’s a project involving information technology, enterprise resource planning, business intelligence, construction, software, development, or any other type of project, the process begins with auditing to figure out what went wrong. Then, leadership needs to determine how to proceed.

Learning from Mistakes to Prevent Future Failures

Moving on after a failing project can be difficult. And while it’s natural, it’s somewhat unhealthy to dwell on failures for an extended period of time. Instead, identify the mistakes, learn from them, and move on. Remember: It takes courage to cancel a project and failure is part of the process.

Some hugely successful companies, products, and leaders emerged only after huge failures:

-

WD40: The lubricant has its name because it refers to the 40th attempt to create a formula that would degrease and protect items from rust.

-

Bubble Wrap: The wrap resulted from a failure to create a textured wallpaper.

-

Pacemakers: These lifesavers used to be huge until a researcher building a device to record a heart rhythm accidentally plugged the wrong-sized resistor into a circuit. The result sounded like a human heartbeat. Additional research gave way to implantable pacemakers.

-

Apple: Several Apple products are listed in the “Famous Failed Projects” section of this article. Leadership turned the company around and now, the tech giant is synonymous with smartphones, tablets, music players, computers, and more.

-

Dyson Vacuums: The founder tested more than five thousand prototypes before finding one that worked. When he was unsuccessful in finding a manufacturer for his product, he began his own company.

Do not discard everything from failed projects. Historical records can serve as reference materials and help future projects. Notes can help keep history from repeating itself.

After making mistakes regarding the time, scope, and budget for a project, learning to set more realistic expectations in the future can help. Paying attention to risk management and being more aware of potential problems can also lead to vast improvements in your future projects.

Improve Project Management with Smartsheet for Project Management

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.