What Is a Crisis Management Model?

A crisis management model is the conceptual framework for all aspects of preparing for, preventing, coping with, and recovering from a crisis. By viewing events through a model, crisis managers gain context and can better apply best practices.

A crisis is an unpredictable or low-probability event that can cause significant negative effects to a business. Often, the causes, consequences, and solutions to a crisis are unclear, yet stakeholders must act quickly.

This definition incorporates the ideas of crisis management researchers such as Christine Pearson and Judith Clair, who in 1998 developed one of the first comprehensive crisis definitions in “Reframing Crisis Management.” In 2007, W. Timothy Coombs put forward another widely cited definition of "crisis" that emphasizes the importance of stakeholders perceiving the unpredicted event as a threat.

To learn more about crises, including the types that most frequently occur in business, read “The Essential Guide to Crisis Management.”

Many models have been developed as part of a larger effort to build overall organizational capacity and skill to anticipate, avoid, and mitigate crises. Therefore, most models emphasize the importance of taking initiative, rather than being reactive.

This spectrum of skillfulness in crisis management can be broadly described as a crisis management maturity model that ranges from reactive to proactive — or even pre-emptive action. To learn tips on becoming more proactive in your strategy, read “How to Craft a Strong Crisis Management Strategy.”

Proactive vs. Reactive Crisis Management Model

The different approaches along a crisis management maturity model, from most to least advanced, are as follows:

- Pre-emptive Crisis Management: This approach seeks to prevent or resolve a crisis at its earliest sign.

- Proactive Crisis Management: In this approach, organizations take initiative early in the crisis and seek to shape how events unfold.

- Responsive Crisis Management: This occurs when there is little warning of a crisis. However, thoughtful and quick analysis can lead to effective action that accounts for long and short-term results.

- Reactive Crisis Management: This is often a panic-driven or knee-jerk reaction. Emotions like fear play a leading role, and objective thinking is largely absent from the crisis response. The company faces crises defensively and, following the crisis, the business may experience problems, high turnover of senior leaders, or even business failure.

A similar model by Can Alpaslan and colleagues focuses on stakeholder involvement and views the crisis management maturity continuum as follows:

- Proactive Crisis Management: All stakeholders that could potentially be harmed should participate in crisis preparation. In the response phase, the organization anticipates knock-on effects and voluntarily discloses the most negative information before the media discovers it.

- Accommodative Crisis Management: The organization accepts that a crisis is possible and involves a broad set of stakeholders in preparation. In a crisis, the company accepts responsibility, voluntarily meets the needs of the victims, and tells the truth.

- Defensive Crisis Management: The business prepares only for crises with high expected costs and involves stakeholders only if required by law. During a crisis, the organization resists admitting full responsibility, but does admit some. The company only does what is mandated by law.

- Reactive Crisis Management: The organization denies the possibility of a crisis and any negative consequences. In a crisis, the company denies all responsibility, closes off communications, and hides the truth. Its stance is uncooperative.

Scenario-Based vs Capacity-Based Model

Until the mid-20th century, organizations primarily faced crises that they had seen before (though of course they were still challenging). The most common threats included natural disasters and labor problems, so companies typically planned for these and other familiar scenarios.

However, the increasing pace of business, advancements in technology, and increasing globalization forced companies to more frequently confront novel and unpredicted crises, such as workplace violence or global pandemics. In this newer context, scenario-based planning holds limited value, since this kind of preparation hinges on facing a known hazard, which triggers a set series of actions.

Organizations fare better by developing their capacities to handle any kind of crisis, even ones that are completely new. Companies can still detail response plans for common kinds of calamities, like fires, but compared to the scenario-based model, a capacity-based model emphasizes building capacities like communications, financial backup plans, and readiness for remote work.

Modular crisis management plans work well in the capacity-based model. Modular plans break down responses into component actions that managers combine and match to the specific demands of the crisis. You can find details on modular planning by reading “Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Crisis Management Plan.” See “Free Crisis Management Templates” to download templates for management plans, helpful checklists, and tabletop exercises.

Fink’s Model of a Crisis and Other Lifecycle Crisis Management Models

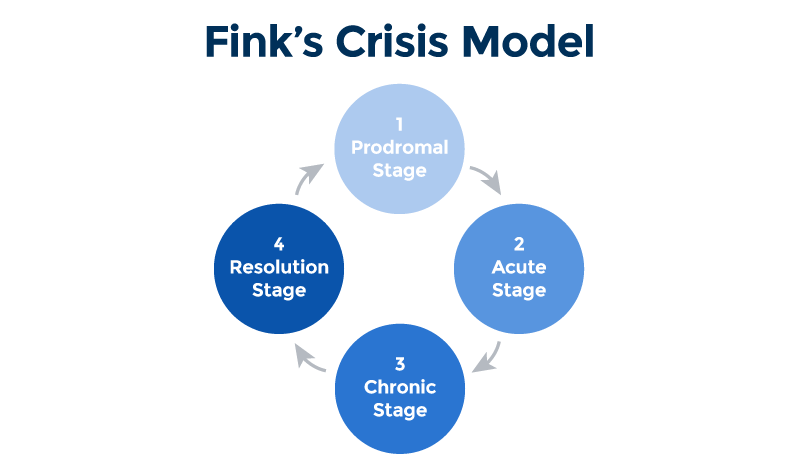

In his influential 1986 book Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable, Steven Fink laid out a four-stage crisis model consisting of the prodromal, acute, chronic, and resolution stages.

The prodromal stage covers the period between first signs and crisis eruption. During this period, Fink states that crisis managers should be proactively monitoring, seeking to identify signs of a brewing crisis, and trying to prevent it or limit its scope.

The acute stage begins when a trigger unleashes the crisis event. This phase entails activation of crisis managers and their plans.

The chronic stage encompasses the lasting effects of the crisis, such as after a flood or a hurricane when teams repair damage to buildings and roads. Finally, the resolution stage represents the end of the crisis and a time for internalizing what went wrong through a root-cause analysis and implementing changes to ensure there is no repetition.

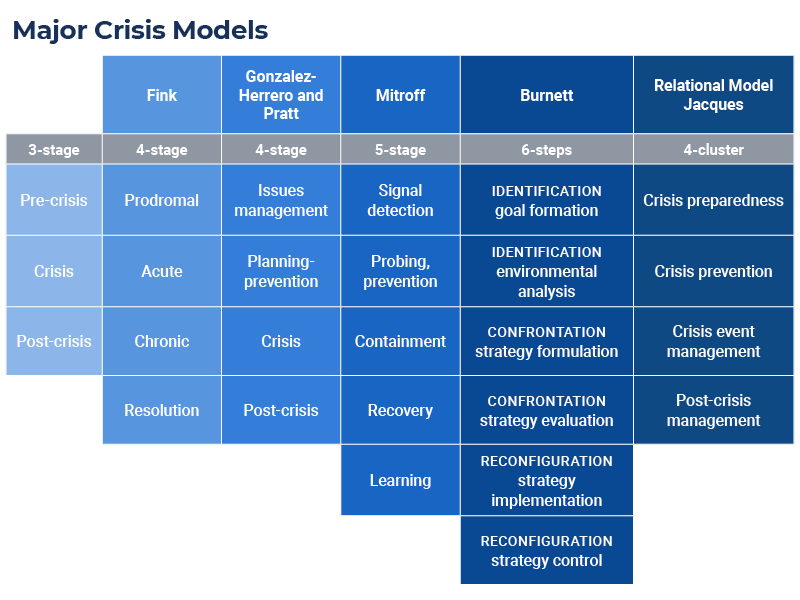

Fink’s model, along with other top crisis management models (including a four-stage model developed by Alfonso Gonzalez-Herrero and Cornelius Pratt in 1996), liken the unfolding of a crisis to a lifecycle with multiple sequential stages. Gonzalez-Herrero and Pratt’s models see the stages as birth, growth, maturity, and decline, and they define a crisis management model that parallels these stages as including issues management, planning-prevention, crisis, and post-crisis. Their model focuses on the communication aspects of crisis management, and the researchers described issues management as a highly proactive phase in which the organization searches for and anticipates issues that may become problematic.

Brand and communications consultant Alan Hilburg explains the crisis lifecycle as an arc that consists of avoidance, mitigation, and recovery.

This concept is similar to another popular model with three stages: before, during, and after a crisis. According to Coombs, the most important models are this three-stage framework, Fink’s, and a third by Ian Mitroff, a researcher who is often considered the founder of modern crisis management study.

Mitroff’s Five-Stage Crisis Management Model and Portfolio Model

In 1994, Mitroff described five crisis stages, which also follow a similar lifecycle progression:

- Crisis signal detection

- Probing and prevention (probing refers to looking for risk factors)

- Containment

- Recovery

- Learning

Mitroff was one of the first researchers to recognize that, due to resource limits, preparing for every conceivable kind of crisis is impossible. He noted that crises tend to fall into certain categories, which Mitroff called clusters, such as breaks or defects in equipment, external actions, and threats (i.e., product recalls). Similarly, prevention actions cluster together, too.

Based on a survey of the Fortune 1,000 companies, in 1988 Mitroff, along with Terry C. Pauchant and Paul Shrivastava, recommended that companies rationalize their crisis management programs by forming dual crisis “portfolios.” The first portfolio consists of crises, one drawn from each crisis cluster, and the second portfolio comprises matching preventative actions from each cluster. Mitroff and his colleagues posited that setting up these two portfolios provides at least minimum coverage across crisis categories.

Burnett Model of Crisis Management

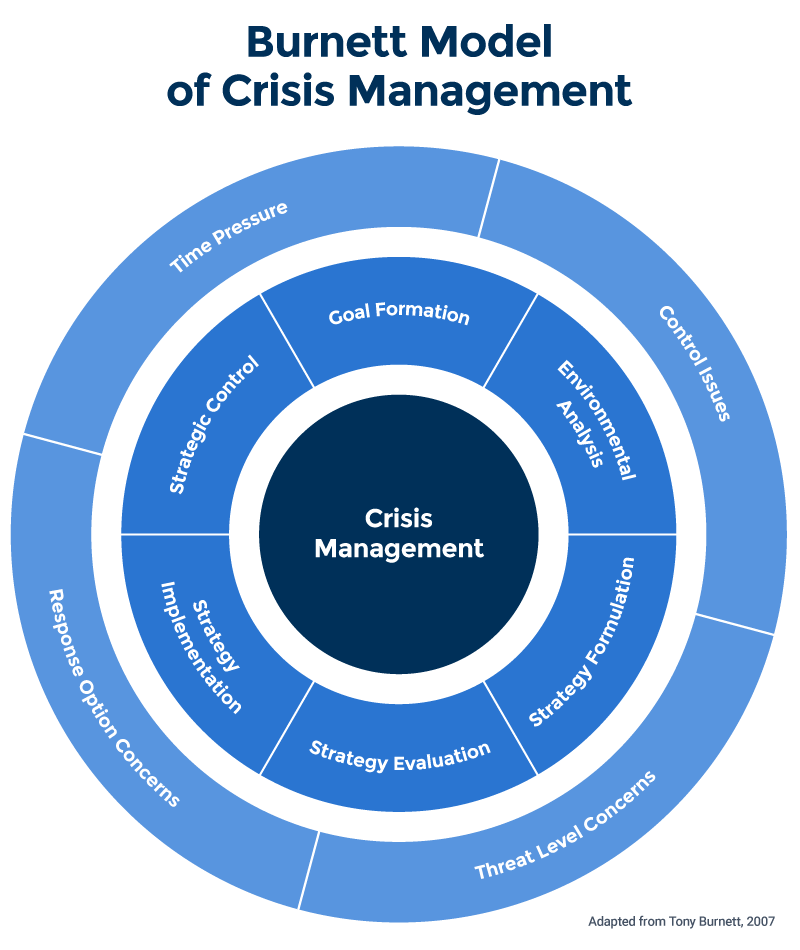

In 1998, John Burnett proposed a crisis management model with three broad stages — identification, confrontation, and reconfiguration — which each consist of two steps. This model also follows a progression like the other lifecycle models. The steps in Burnett’s model are goal formation, environmental analysis, strategy formulation, strategy evaluation, strategy implementation, and strategic control.

Preparing for a crisis involves goal-setting and analyzing the threat environment. Managers then formulate a strategy in the face of a crisis, and the organization responds to the crisis via strategy implementation and strategic control (the latter stage includes the oversight of crisis management actions as well as post-crisis review).

Burnett held that the process is more difficult to master as the steps progress. In an outer ring, he arrayed factors that stand in the way of crisis management, including time pressure, control issues, threat level concerns, and response option constraints. In this sense, the model functions like a matrix.

Relational Model of Crisis Management

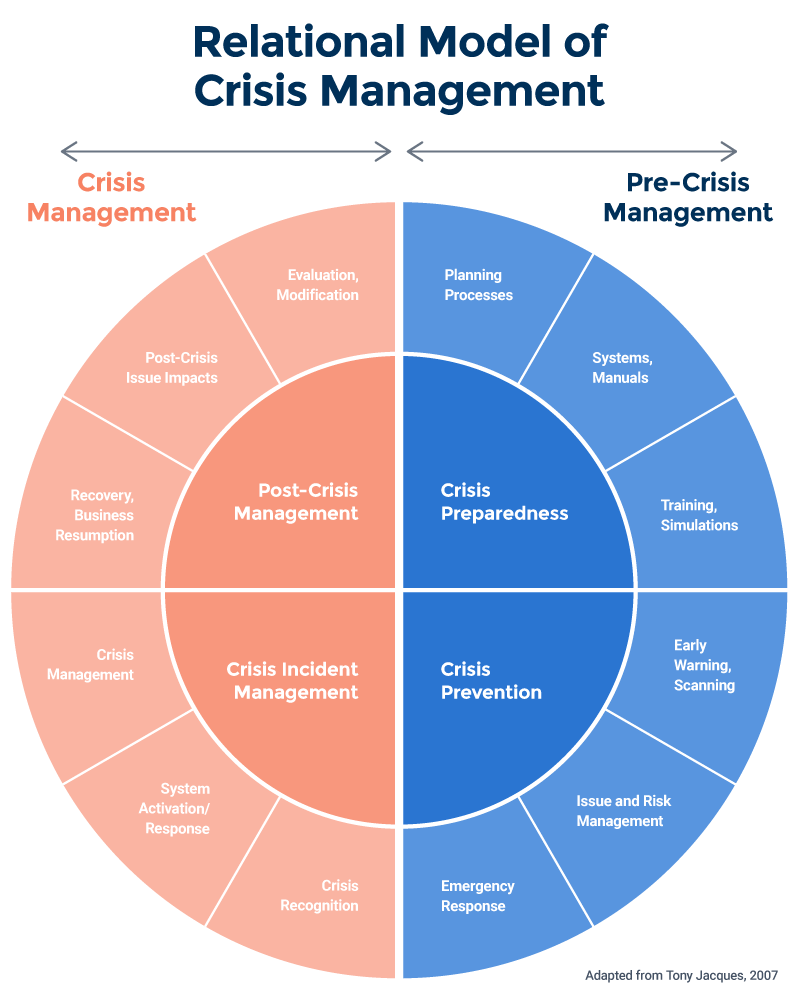

In 2007, Tony Jacques took issue with the idea that crisis management is a linear process of sequential phases in which you manage issues one at a time. Instead, he argued that important processes and activities often overlap or occur simultaneously, such as crisis prevention and preparation, and don’t always proceed in one direction.

As opposed to the lifecycle models, Jacques proposed that crisis management and the field of issue management are related, integrated disciplines. Issues management involves creating systems to deal with problems — while issues are more routine than crises, they overlap because issues can become the source of crises if not properly dealt with.

Jacques’ relational model has four primary elements — crisis preparedness, crisis prevention, crisis incident management, and post-crisis management — each with clusters of activities and processes. He concluded that understanding the relationship among these elements, and putting them in context of larger organizational management, diminishes crisis-related losses.

Incident Command System Model

The incident command system model is unique in that it originated in the real world and was then formalized as a model (other models began as conceptual frameworks). Incident command started in the 1970s as a model for California agencies to manage wildfires.

The incident command system divides work into five broad areas, including operations and logistics, as well as a hierarchy of roles and responsibilities for key players that provides a clear chain of command and communication. Each fire department or company site replicates the structure, so teams automatically know their counterparts and share common terminology and integrated communications. Therefore, coordinating and working together becomes relatively straightforward, and teams spend less time organizing the response and more time actually responding. You can learn more about this process by reading “How to Build an Effective Crisis Management Team.”

The incident command system model is useful because it offers a framework for the unified command of a crisis, scales well, makes efficient use of resources, and facilitates communication among people from different departments or organizations.

When the 9/11 attacks on the United States occurred, organization problems hampered an early response. There was initially no coordination agency, and first responders from different agencies struggled to communicate due to incompatible technologies. Additional offers of help flowed in chaotically and slowed down the response.

Implementing incident command solved many organizational challenges. In 2003, this experience prompted the U.S. government to make incident command mandatory for all publicly funded U.S. agencies. Incident command spread both nationally and internationally, and has since been adopted by many private-sector organizations, too.

U.S. private-sector businesses that deal with hazardous materials and nuclear power are also required to use the incident command model. Many organizations that interact with the public sector (for incidents such as mass casualties and fires) have also embraced the model because it facilitates their cooperation with emergency services. These organizations include schools, universities, transportation systems, chemical plants, and critical infrastructure like power, water, and communications.

Crisis Management Model Example

Incident command systems managed the complex web of activities that took place during the Deepwater Horizon oil well explosion and spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, which resulted in 11 deaths and massive contamination.

The crisis response represented an enormous management challenge. More than 40,000 personnel joined from the public and private sectors — the effort was the largest mobilization of resources to address an environmental emergency in the history of the United States, according to the U.S. government. For more crisis management examples, please see “The Most Useful Crisis Management Examples: The Good, Bad, and Ugly.”

Most Influential Crisis Management Theories

Although the two terms are often used interchangeably, a crisis management theory is distinct from a crisis management model, as models seek to represent the structure or application of crisis management, while theories are more abstract concepts.

Some of the most well known crisis management theories include attribution theory, situational crisis communication theory, stakeholder theory, and contingency theory. Theories from management studies and other disciplines have also been applied in crisis management, including the diffusion of innovation theory, resilience theory, and human capital theory.

Attribution Theory and Situational Crisis Communication Theory

Attribution theory holds that companies suffer reputation and business harm when the public blames them for a crisis. Situational crisis communications theory builds on this idea by recommending that businesses tailor crisis communications to the crisis’ potential to hurt the company’s reputation.

People closely associate Coombs with both these theories: Attribution theory starts from the premise that it is human nature to seek to explain why events occur, especially sudden and damaging incidents like crises. Typically, people attribute responsibility to an entity, such as a company, or a situation. When people blame an organization, they direct negative emotions toward it. Coombs found that this can result in damage to the organization’s reputation, reduced intention to do business with the company, and increased tendency to speak negatively to other people about the organization.

While Coombs didn’t anticipate the power of social media to amplify reputational harm, tweets and other posts can be an especially damaging form of the negative word-of-mouth he described. These networks have introduced a level of rapid two-way communication between consumers and companies that previously did not exist, testing the ability of companies to control the messaging. Therefore, social media management is an essential part of crisis management.

In situational crisis communications theory, Coombs said crisis managers must first determine the threat to the company’s reputation by assessing which of three clusters the crisis fits into:

the victim cluster (the organization is a victim); the accidental cluster (the organization unintentionally caused the crisis); or the intentional cluster (the organization intentionally acted wrongly). The clusters have escalating potential to harm the company’s reputation because of the level of responsibility attributed to the company (minimal, low, or strong).

Based on an assessment of the situation and reputation risk, Coombs believes the organization should respond with one of three strategies: deny, diminish, or rebuild. In deny strategies, the organization assumes no responsibility; diminishing strategies seek to downplay the seriousness of the crisis; and rebuilding responses tend to involve apologizing.

Secondary responses are referred to as bolstering, and include reminding (for example, drawing attention to the company’s past good deeds); ingratiating (praising stakeholders); and victimizing (pointing out the organization’s status as a victim, too).

Coombs compiled the following 10 crisis communications best practices based on attribution theory, including apologizing in certain circumstances:

- Provide all victims or potential victims with instructions, such as recall information.

- Express sympathy to all victims, along with information about corrective actions and trauma counseling.

- For crises in which the organization faces minimal blame and there are no so-called intensifying factors (history of crisis and negative past reputation), the above two steps will suffice.

- If there is an intensifying factor, offer excuses and/or justification.

- The same response applies to a crisis in which blame is low and there is no crisis history or poor past reputation.

- If there is low attribution of responsibility and an intensifying factor, add compensation or an apology to the first two steps.

- If the public strongly attributes responsibility to the organization, offer the first two steps as well as compensation or an apology.

- Use compensation any time a victim experiences serious harm.

- Supplement any response with the remind and ingratiate strategies.

- Save denial and attacking the accuser for crises that involve rumors and challenges in which a stakeholder contends the organization is acting wrongly.

Theory of Apology

Researchers recognize the powerful role that apologies play in crisis management. This has been formalized as an area of study under the term corporate apologia, which means using rhetoric to protect your reputation while explaining what happened.

In apologia, the crisis response options are denial of responsibility, shifting of responsibility, or taking full responsibility with an apology.

In Keith Michael Hearit’s 2011 book Crisis Management by Apology, in which he developed the theory of apology, he states that companies often avoid apologies in favor of making no public comment because of concerns that apologizing increases their liability or weakens their position in lawsuits. However, Hearit contended that a public relations-driven strategy, in which the organization apologizes and seeks to be candid, is more effective.

Later research by Coombs and Sherry Holladay contradicted this statement, finding that apologizing isn’t necessarily more effective in reducing reputation damage and negative word-of-mouth among stakeholders who are not themselves victims. In these studies, apologizing was about as effective as other victim-centered strategies, such as expressions of sympathy and compensation.

Image Restoration or Repair Theory

Image repair theory, also known as image restoration theory, shares a focus on rebuilding an organization’s reputation when it has been damaged by a crisis.

Communications scholar William Benoit originated image restoration theory in his 1995 book Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies: A Theory of Image Restoration Strategies, which focuses on the messages a company should communicate during a crisis. He offers five categories of image repair strategies: denial, evasion of responsibility, reducing perceived offensiveness of the action (such as with compensation), corrective action, and mortification (confessing and begging forgiveness).

Structural Functional Theory in Crisis Management

Structural functionalism comes from sociology, and looks at society as a structure made up of institutions that function together to keep the whole running, like organs that work together to keep the body functioning.

In crisis management, this theory explains how organizational communication relies on a structure made up of networks for information to flow and a hierarchy of people who manage the process.

Chaos Theory and the Butterfly Effect in Crisis Management

Chaos theory comes from mathematics, and holds that some systems are so complex that small differences in starting conditions can make them act very differently and unpredictably.

This characteristic inspired the concept of the butterfly effect, in which a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can theoretically cause a tornado in Texas. This potential (for small changes to have unpredicted effects) can make these systems appear completely random, even when they may not be.

Researchers have applied both chaos theory and the butterfly effect in crisis management. For example, they studied officials who made precise and rosy predictions about disasters without taking unpredictable weather variables into account. This occurred in Canadian floods in 1997, wherein inaccurate communication meant that many communities were not prepared for the scale of a disaster that occurred.

In the corporate world, chaos theory can show the limitations of controlling volatile public perception of a crisis.

Stakeholder Theory of Crisis Management

In 2009, Alpaslan, Mitroff, and Sandy Green published a theory that focused on the role of stakeholders in crisis management. They argued for including stakeholders in crisis preparations and responses — not because of their power or influence on financial value, but due to factors such as potential for injury.

Crises can reorder the importance of a stakeholder group, and managers who understand stakeholder theory consider and incorporate the needs and values of a range of stakeholders, Alpaslan, Mitroff, and Green said.

Resilience Theory and Business Continuity Planning

Resilience theory, which has its roots in child psychology, holds that having one or more protective factors can help individuals survive adversity with less harm. In business, resilience theory helped give rise to business continuity planning, which seeks to make companies more resistant to failure.

A business continuity plan is similar to a crisis management plan in that it anticipates emergencies and disruptions that could occur and defines actions to regain normalcy in the company. Read “Business Continuity Planning: How to Do It Well,” to learn more about that process.

According to researcher Patrice Buzzanell, resilience theory outlines five elements that businesses can cultivate to strengthen their ability to bounce back: crafting normality, affirming identity anchors, making use of communication networks, putting alternative logic to work, and emphasizing positive feelings while downplaying negative ones.

Integrated risk management is another resilience-boosting business practice. In integrated risk management, company culture is attuned to risk, and organizations seek to evaluate the risks in all their activities jointly, rather than in isolation. Technology-enabled practices support this integration, and the result is better risk-reduction decisions for the whole enterprise.

Contingency Theory

Contingency theory asserts there is no single best method to organize or lead a company, and that decisions should be made contingent on circumstances. Researchers say this applies equally in crisis management, because crises are fluid, complex, and uncertain. Crisis managers must adapt their response to make it contingent upon the situation.

Crisis leaders and communicators should take into account a range of external factors, such as threats, the marketplace environment, social and political support, the characteristics of public stakeholders, and the complexity of the issue.

Internal factors include characteristics of the organization and other threats.

Diffusion of Innovation Theory

The diffusion of innovation theory describes how new ideas spread and become accepted. According to Evertt Rogers, who pioneered the theory in his 1962 book Diffusions of Innovations, a small minority of people initially adopt innovations. When about 20 percent of the population adopts a new behavior, 70 percent of the remaining people will adopt it, too.

This idea has influenced crisis management by shaping efforts to change behavior and attitudes in emergencies. Specifically, the diffusion of innovation theory can identify behaviors that might be most easily changed, the people who might adopt new practices (and influence others), and the most effective ways to spread new ideas.

An example application of this theory is the effort by public health agencies to get people to wear masks during a pandemic.

Theory of Human Capital

The theory of human capital comes from economics, and frames individual characteristics such as education, health, and birthplace as factors that contribute to a person’s productivity and income.

In crisis management, inequalities of human capital — such as disadvantages in education and healthcare and unfair income distribution among classes and races — can lead to or exacerbate crises. For example, when reflected in lower wages or job status, these inequalities make companies vulnerable to discrimination lawsuits, damaged morale, and reputation harm.

Improve Your Approach to Crisis Management with Real-Time Work Management in Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.