What Is Construction Bidding?

A construction bid is the process of providing a potential customer with a proposal to build or manage the building of a structure. It’s also the method through which subcontractors pitch their services to general contractors.

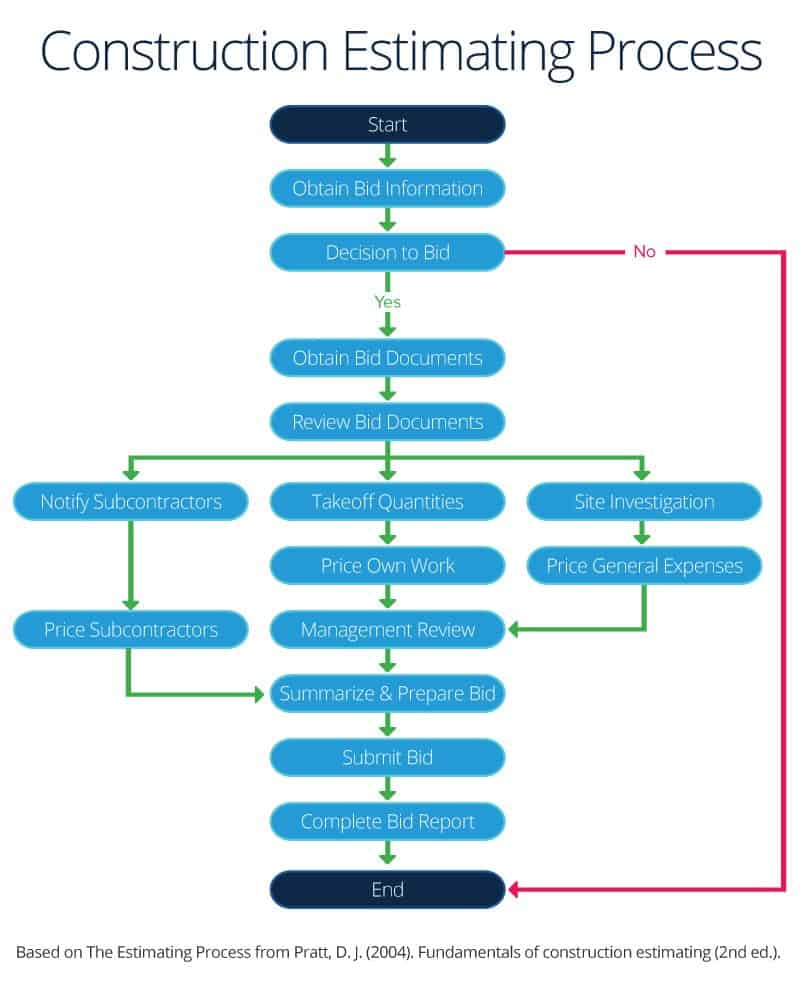

In order to create successful construction bids, remember the industry golden rules: Start with highly accurate cost estimates, and submit the lowest bid of all the competing contractors. The process of forming a bid begins with examining construction plans and performing material quantity takeoffs. If you're interested in learning more about construction planning, visit this comprehensive guide to construction plans. However, there are a lot of nuances and complexities behind this seemingly straightforward formula. We will delve into those in detail later on.

First, it’s important to distinguish between a bid and an estimate, terms that are sometimes used interchangeably. The definitions of the two are somewhat elastic. Generally, an estimate is the calculation of the contractor’s internal costs (including materials and labor), while a bid is the final price charged to a customer. We consider a bid to be a firm offer to the customer. The difference between the bid amount and your expenses is your profit. Using construction bidding software can help ensure you’re bidding the right amount. Sometimes, on small jobs, the customer may move quickly after reviewing just an estimate, treating it, in effect, as the bid that will represent the formal terms of the deal.

Estimates should be as accurate as possible, progressing through levels of precision from preliminary or ballpark to square foot, assembly, and final estimate.

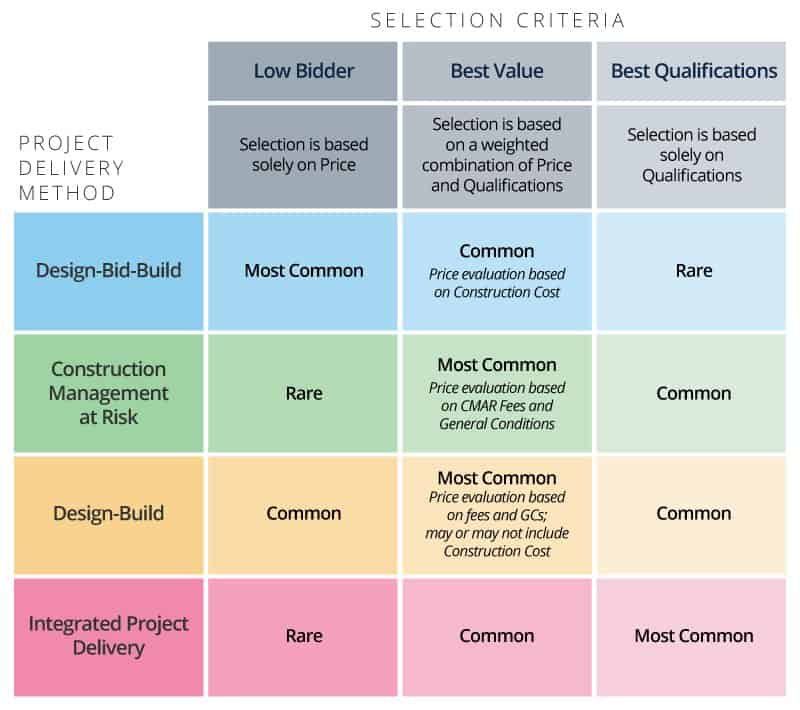

In construction bidding, price is always a key consideration. On many projects, especially in government construction, the owner must choose the lowest bid. On other jobs, however, qualifications or other factors can be equally or more important than price. The selection process depends on the project delivery method — we’ll break down the different methods shortly.

The basic construction tender process involves the following activities:

- Bid Solicitation: The owner seeks bids and provides a package of material with drawings, specifications, and other scope documents. This is also known as making a request for proposal (RFP) or a request to tender (RTT),

- Subcontracting: General contractors take bids from subcontractors for pieces of work. Depending on the project method, this may occur after a general contractor wins a bid.

- Bid Submission: Builders submit bids by a deadline.

- Bid Selection: The owner reviews bids and chooses a winner.

- Contract Formation: This phase finalizes the terms and lays the legal groundwork for the project.

- Project Delivery: Construction takes place.

Transform construction management with Smartsheet. See for yourself.

Would you like to manage your construction projects more efficiently, get better visibility into project risks and dependencies, and optimize resource planning?

Smartsheet empowers construction teams of all sizes to improve visibility to critical information, boost collaboration across field and office teams, and increase overall efficiency, so you can deliver projects on time and on budget.

Three Major Decisions Shape Construction Bidding

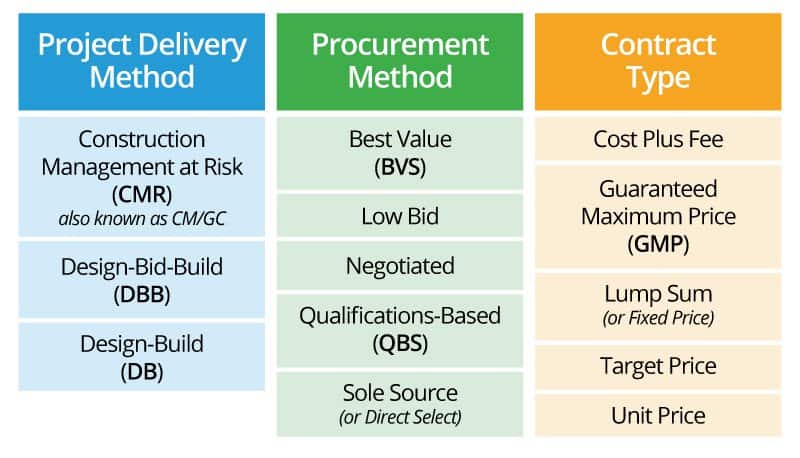

To bid on construction, you need to understand three important structural decisions that owners make and that shape construction projects. An owner must decide on the following elements:

- A project delivery method

- A procurement method

- A contract model

We’ll explore each of these three elements in detail. Each choice that an owner makes translates into different responsibilities, risks, costs, and profit formulas for the bidder. To succeed as a bidder, you must understand how these decisions impact you and design your bid to ensure you are competitive, make sufficient profit on the project, and account for the risks you will bear.

Construction Project Methods

First, let’s look at project delivery systems. There are four major methods for delivering construction projects. While they vary in approach, they share the common goal of helping owners build new structures on time, within budget, and in line with quality and performance requirements.

As a construction bidder, you will see that each method defines your role, responsibilities, and risks somewhat differently. Some methods share similarities.

Traditional project delivery also goes by the names design-bid-build (DBB) and design-tender and is the most common process for the construction of nonresidential buildings, especially government projects. In this approach, an owner hires an architect or designer independently from the contractor who manages construction.

The owner selects an architect who develops complete designs. Then, the owner solicits bids from contractors to execute the designs. The bid covers the total cost of building the structure, including any money for subcontractors who work under the general contractor. The bid also incorporates the general contractor’s costs, overhead, and profit.

Some advantages of DBB are owner control of design and construction and ease of implementation. In addition, because an architect finishes a design before an owner awards a construction contract, it is easier to determine the cost of construction. The drawbacks of this particular project delivery system include that the owner must bring substantial expertise and resources, and also share responsibility for project execution. The owner is also at risk of dealing with increased contracting costs if there are any design errors.

Multi-prime, also called multiple-prime, contracting is a variation on design-bid-build. Here, the owner contracts directly with all participants, including the architect, subcontractors, and a construction manager (either an owner staff member or a hired party). In this scenario, the owner acts as the general contractor.

Owners turn to this method when they need to fast-track construction or when there are urgent considerations. Project managers can solicit bids for each of the project’s systems or specialties as soon as the project’s design is complete, which gives them greater control over the schedule.

Multi-prime contracting also enables the owner directly to obtain materials for the project. Rather than obtaining materials through the general contractor, the owner can avoid markup and be certain that materials will be available when needed.

Multi-prime also works well when construction proceeds in phases. The owner enters contracts sequentially for each part of the job (for example, foundation would come first, followed by structure).

There are several drawbacks to the multi-prime delivery system. The owner carries the heavier burdens of coordination and management as well as the resulting increased risks of work duplication or omission. The owner cannot confirm the final cost of the project until they’ve secured the last contractor. There is a higher potential for poor coordination, change orders, quality defects, and delays due to the number of project participants. Plus, multi-prime projects sometimes suffer from a lack of strong central authority and management among the contractors. In DBB, the general contractor would play the role of that strong authority figure.

In design-build, aka D-B or D/B, the owner contracts with one entity that handles both design and construction, and one price covers both phases. That entity goes by the title design-builder or design-build contractor.

The design-builder concept has its roots in the historic master builder, who in pre-Renaissance times was a highly skilled individual responsible for both the design and construction of a structure. During the Renaissance, the roles of designer and builder split, and each position became more distinct and specialized over time.

Owners find design-build attractive because it streamlines the process of commissioning a new building, and it increases collaboration between project participants. The design-build firm usually contracts out some aspects of the project rather than doing everything in house, but all participants work together on the same team. Proponents cite this characteristic of collaboration as an advantage over traditional design-bid-build. This is because one of DBB’s greatest vulnerabilities is the potential for conflicts and disputes to arise among all the independent parties when things go awry.

In design-build, the design-builder stands accountable to the owner for all aspects of the project. The Design-Build Institute of America says that when one person possesses sole responsibility for a job, owners experience better project delivery, including faster execution, fewer change orders, reduced administrative burdens, lower costs, and fewer disputes that result in litigation.

According to research by the Construction Industry Institute and Penn State University on 351 projects from 5,000 to 2.5 million square feet, design-build achieved 6.1 percent lower costs and 33.5 percent faster delivery speed when compared to design-bid-build. Having faster delivery also creates financial benefits since construction loans, carried while workers are building a structure, charge higher interest rates than those of permanent financing, which kick in when the project is done.

Design-build has become increasingly popular. A 2013 DBIA study found that owners used this method on more than 40 percent of non-residential construction projects in 2010, up 10 percent since 2005.

Within design-build, there are different models. One of these models is contractor-led design-build (CLDB), also called builder-led design-build, in which the general contractor manages the project. CLDB accounts for most design-build projects. Recently, the architect-led design-build (ALDB) model, also termed designer-led design-build, has grown. In ALDB, the architect is responsible for delivery of the building. A 2005 survey cited by Architectural Record magazine found that 55 percent of design-build projects were headed by a contractor, 26 percent by an integrated firm with both design and construction expertise in house, and 11 percent by designers.

A third design-build school of thought contends it does not matter which specialty holds the primary contract for the project; either can do just as well. Project-led design-build, in which the project team consists of a cohesive unit of all the job’s disciplines, always puts the project’s best interests first.

While design-build has compelling data on speed and cost, construction experts say that it also has disadvantages. The design-builder’s very incentive to reduce speed and cost can impact quality and put the owner at the mercy of the contractor, who may or may not act with integrity and expertise. Also, because the architect works for the design-builder rather than for the owner, the architect does not represent the owner’s best interests. (In DBB, the architect does work for the owner and therefore represents their best interests.) Moreover, because there are so many unknowns about the future of a building at the beginning of a D-B project, owners must define more of the project’s requirements, objectives, and materials before soliciting bids.

With no construction documents yet to work from, design-builders also assume risk in cost estimating because the scope of work is not well defined. Contracts on design-build projects can address how to handle unexpected developments without financial penalty to either the owner or the designer-builder.

Construction manager at risk (CMAR), also called construction management at risk, CM at risk, CM@R, construction manager/general contractor, and CM/GC project delivery, is another alternative to traditional design-bid-build and has a track record for reducing cost.

Like design-bid-build, in the CMAR method, different firms handle design and construction. Unlike design-bid-build, however, the construction manager joins the project at the start before the architect designs the building; the construction manager may even help choose the architect. The CM and the architect work together during the design phase. The construction manager acts as a consultant to the owner during the design and construction phase and often handles some of the construction itself.

The construction manager transitions to a general contractor when construction begins. You use this method primarily for complex projects and choose the construction manager on the basis of expertise and qualifications, not lowest price.

The construction manager’s bid to the owner is a guaranteed maximum price (GMP) representing the total of pre-construction services, actual construction, and the construction manager’s fee and contingencies. According to an article by Tommy Brennan, Business Development Manager for Ulliman Schutte Construction, most CMAR projects require the contractor to provide the GMP when the design phase is 60 to 90 percent complete.

When the design is complete, the construction manager solicits bids from subcontractors to execute the project. The construction management firm takes on the risk that bids may come in higher than the GMP.

In the CMAR method, you shift some of the project risk to the construction manager because if actual costs exceed the GMP, such as through higher subcontractor bids, change orders, or imprecise forecasting, the owner does not bear that burden. If the construction team builds the project for less than the GMP, the owner may receive the savings, or the owner may have an agreement to share them with the construction manager.

The benefits of this approach for owners include greater cost control, reduced risk, and superior project management. The construction manager can work with the architect and the owner during the design phase to make sure that the construction team can build the plans within budget, and the owner knows upfront what the project will cost. The project may also move faster because you may be able to start construction before the design phase is complete.

The construction manager acts on behalf of the owner and manages the project with the owner’s best interests in mind. In addition, the construction manager brings expertise regarding value and constructability. These attributes translate into fewer burdens on the owner and ensure a high quality outcome.

On the negative side, the owner must cede some project control to the construction manager, and, as both a contractor and a project manager, the construction manager may face some conflicting priorities.

CMAA, the national organization for construction management, has training and resources for both owners and construction managers on the types of projects best suited for this method.

The general consensus among construction professionals is that CMAR saves time and money compared to design-bid-build, but not compared to design-build. However, quality can be higher with CMAR than with design-build, and CMAR is a better match for larger, more complex projects than design-build is.

Integrated project delivery (IPD), sometimes called integrated team, is the newest of the major project delivery methods. This method sets up the owner, the architect, and the contractor as a team that shares risk equally. Often, they become legally bound in a single contract, and this may expand to include other consultants and subcontractors.

This approach strives to increase efficiency through collaboration and integration. The United Kingdom’s Office of Government Commerce estimates 30 percent of construction costs can be saved when integrated project teams work together and seek continuous improvement across a series of construction projects. Single projects with integrated teams can save two to 10 percent.

Early participation of the general contractor and continued active involvement by the owner are hallmarks of IPD. This closer cooperation drives the advantages of IPD, and project participants generally have fewer disputes, claims, and conflicts. Therefore, the absence of litigation and arbitration offers another source of cost savings and efficiency.

Because the architect and contractor participate in the project entity equally, they are a jointly accountable. In discussing the advantages, IPD specialist firm gkkworks notes, “Experts in design and construction contribute to ALL phases of the project.”

However, there are some drawbacks: Finalizing project criteria and reaching a contract can be difficult and time consuming, the CMAA says. In addition, the smooth management of the team may depend most on the individuals involved, and team selection can be challenging.

The method works well for complex private projects, projects with tight deadlines, or those where the scope is not well defined. Government entities usually are barred from IPD because it lacks competitive bidding. The American Institute of Architects has compiled an in-depth guide to implementing IPD.

Construction Procurement Methods

Once project delivery method is selected, the owner faces the decision of how it will procure construction services. A number of factors influence this decision. Government owners often fall under laws that dictate how they must make purchasing decisions.

Other influences include the political, economic and social environment, the owner’s experience and expertise in construction and construction procurement, the size, complexity, location, and uniqueness of the project, the timing of the project and whether schedule compression is needed, and cost considerations such as how much price certainty the owner needs.

Construction procurement is generally divided into four types: lowest bid, traditional, integrated, and, negotiated and managed.

Traditional procurement aligns most closely with the traditional project delivery method, design-bid-build. The owner buys construction services separately from design work, tenders for construction bids after design is complete, and the construction bidder knows all the project specifications before bidding.

The most common procedure in this case is competitive bidding with the lowest bidder winning. It’s often called low bid or lowest bid procurement. Governments and other public entities commonly use this method because laws, drafted in response to bribery scandals, require them to prove they received the best possible price in a process free from corruption. In those cases, bids are opened and reviewed publicly.

In competitive bidding, contractors are invited to submit their best bid by a deadline, and the owner compares bids against one another. This is called sealed bidding. Because the bids are all to build the structure according to the designs and specifications developed by the architect (i.e. the same product), the contractor who bids the lowest amount wins. In fact, the bid number may be the only piece of information reviewed.

However, this process does not work for all projects. In two-step bidding, a first round of review examines the technical qualifications of all the bidders. Bidders must show they have the skills and experience to handle the project. This is common in specialized structures. Because the financial and operational consequences of flawed or incomplete construction are damaging, it makes sense that an owner commissioning a hydroelectric dam, data center, or hospital would want assurances that the builder has demonstrated expertise in this type of project.

In two-step bidding, the owner creates a short list of those bidders who meet the technical qualifications. Bids from contractors who passed the first round move to the second round. Their proposals are called qualifying bids, meaning that they meet the requirements of the customer for technical expertise. (Other benchmarks can also be used, such as being able to build quickly enough to meet a specific completion date or to comply with government requirements for using a certain percentage of locally owned subcontractors.)

In two-step bidding, the lowest qualifying bid wins. The U.S. federal government uses this method to award indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (IDIQ) construction contracts under federal acquisition regulations. IDIQ contracts cover an unknown amount of services over a set period of time. In construction, IDIQ is often used for architect and engineer services and job order contracting (JOC).

Job order contracting was developed in 1982 by Harry H. Mellon, then chief engineer in Europe for the U.S. Army, and it spread to all branches of the military and levels of government, including housing authorities and school systems. Under JOC, an owner gets a long-term umbrella contract that sets a unit price for common renovation, repair, or small construction jobs. When the need arises, the owner calls on the contractor to perform the work as agreed in the contract. This system creates efficiencies: Since owners do not have to identify contractors and negotiate contracts each time they need a job done, the work begins more quickly. And because prices are fixed on work and materials over a larger cost base of multiple jobs, economies of scale are realized. Costs of procurement are also reduced. The Center of JOC Excellence has extensive education resources that explain the advantages of job cost contracting and how to get going with it.

Best value source selection is a procurement method in which buyers award contracts based on other factors as well as cost. The goal is to achieve the best combination of price and performance. In this process, the owner (usually a government agency) will define source selection criteria that add value to a bid. These can include past performance, more robust management approach, highly qualified key staff, or other factors. Using best value selection gives owners, who might otherwise be compelled by law to choose only on price, greater flexibility.

The implementation of best value selection can be similar to two-step bidding. In a best value selection process, bidders might first submit their qualifications based on the defined selection criteria; those that pass then submit technical and price proposals. Best value selection can also proceed in a single step process with qualifications, technical, and price proposals submitted simultaneously. A good guide on best value selection has been developed by the Associated General Contractors of America and the National Association of State Facilities Administrators.

Under negotiated procurement, an owner selects a contractor without advertising or competitive bidding. The U.S. government uses this method and negotiates with the potential builder on price and technical requirements. It awards the project to the contractor who makes the proposal most favorable to the government. The proposals are not publicly opened.

Unlike tendering (in which a proposal is accepted or rejected), in this method, contractors’ proposals are subject to further negotiations with project managers. After analyzing the proposals, they proceed with those that appear to meet broad technical and cost specifications. The two sides discuss the project details, objectives, conditions, schedule and cost, and then bargain over the variables. The contractor who offers the most attractive proposal wins. While the process is competitive, the competition may not focus on price, but rather on a range of factors such as technical ability. This method allows greater flexibility to finetune the deal in terms of management approach, technical solution to a problem and terms.

In private projects, the owner may go through this process with just a single bidder. Anderson-Moore Construction Corp in Lake Park, Florida argues that the negotiated approach offers owners greater value because the contractor can identify changes and cost savings before the project starts, eliminating the need for change orders.

U.S. federal negotiations favor sealed, competitive bidding procurement, but allow negotiated procurement in certain defined cases.

Sole source procurement, also known as single-source procurement, direct select, or a no-bid contract, is a non-competitive method you use when only one provider can fulfill the requirements of the project.

Government agencies can justify not using competitive bidding process in certain situations, such as emergencies or if, due to unique and complex specifications, only one contractor is capable of handling the project. Another reason would be if the new structure interfaces or connects with another specialized building, and the owner wants to make sure the two are compatible, like an expansion of a wastewater treatment plan using proprietary technology.

But sole source procurement can be vulnerable to abuse, so government buyers should proceed with caution.

In business, owners may decide on sole source procurement if, for example, they have a successful relationship with a contractor and want to replicate a prior contract or project. Private parties are not required by law to comply with competitive-bidding regulations unless they are receiving government funding, and they may feel the time and management effort saved with this approach offers strong business rationale.

Digital Procurement and Online Construction Bidding

Digital procurement of construction services is becoming the norm. While the method is new, the underlying procurement models have not changed. For example, sealed bidding got its name because bidders would submit bids in sealed envelopes. Today, online bidding systems have made paper envelopes obsolete, but bidders still confidentially tender competitive bids in virtual lock boxes.

Digital procurement uses websites and software as a service (SaaS) platforms to handle tender calls, requests for proposals, requests for quotes, design bids, distribution of bid documents, bid submission, and other parts of the procurement process. Standard formats and reusable templates facilitate the preparation of bid packets.

These systems make it possible to disseminate and share large amounts of paperwork, including construction drawings. Users are generally required to register to access a database of tender opportunities. The system will notify users of due dates and any changes in project specifications.

Such systems are more efficient than paper bidding, and they make it easy for government agencies to show they are informing all bidders simultaneously and giving them equal access to information. They also provide audit trails, which are helpful in the event of a bid protest.

Once a winning bid is selected, these systems also assist in contract management with performance reviews, sample letters, clause commentaries, and more.

Contract Options in Construction Procurement

In developing a construction bid, pay close attention to the contract format that you propose. Often, the owner will dictate what type of contract it is willing to enter. The type of contract will determine how your costs and profit will be covered. The following are among the major contract types:

- Cost plus Fee/Cost plus Percentage: A contract in which the buyer agrees to pay for all supplies and labor, as well as an additional amount for contractor profit.

- Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP): Also called not-to-exceed price, NTE, NTX, or open-book contract, this contract sets a ceiling on how much the owner will pay. The contractor is responsible for any excess or overrun, unless there has been a formal agreement on scope change. If the project costs less than the GMP, the owner retains the savings or may have an agreement to share them with the contractor.

- Lease Leaseback: A contract in which the owner leases the property to the builder who is required to construct a building on the property. The original owner then leases it back and regains title to the property at the end of the lease.

- Time and Material: A contract in which an agreed-upon price is set based on the time involved and materials used for the project.

- Hard Bid/Fixed Price/Stipulated Lump Sum: A contract in which the contractor accepts one total sum for all components on the project. This is generally used for projects that have well-defined costs and components. The builder does not have to provide a cost accounting of the completed work. Additional payments may be included as incentives for early completion or penalties for delays.

- Percentage of Construction: A less common form of contracts in which the compensation is based on a percentage of construction costs.

- Unit Price: A contract in which the final cost is determined based on the unit prices of work, including materials and services.

- Target Price: The owner and the contractor set a targeted price for the project, and the contractor tries to meet or come in below that price. The price includes base costs such as subcontractor costs, contractor overhead, and profit. The owner reimburses the contractor for his actual costs. The owner and contractor share any cost savings or overrun under a formula agreed-upon in advance.

Construction Bidding on Residential Projects

The methods and models we have discussed so far generally relate to commercial and public projects. So if you are bidding on single-family residential construction jobs, very little of this will be relevant to you. Residential construction consists of a few major project types:

- Remodels and Renovation: Existing homes are updated or expanded by their owners, who intend to continue living there.

- Custom Home Construction: An owner commissions the building of one house on a specific site for their family.

- Speculative (“Spec”) Home Construction and Remodeling: A home built or remodeled by a builder, investor, or developer with no specific buyer in mind. These projects are usually driven by the belief that the house can be sold for more than was spent on construction.

- Subdivisions and Tract Homes: Multiple homes built by big construction companies on large vacant sites. The house styles and floor plans are similar, and the volume and replicability enable the builder to achieve a much lower cost per square foot.

- Multifamily Dwellings: Apartments and townhomes are also mostly the province of developers and large construction companies.

The last two types of projects have much more in common with real estate development than with other types of home building, and construction bidding on these projects is more like the process for commercial work described earlier.

For homeowner remodels and renovation and new custom home construction, owners and/or their architects will generally use competitive bidding or cost plus fee contracts. With competitive bidding, contractors with experience building specific styles or certain price points or technical expertise will be invited to bid based on project specifications.

In cost plus, contractors get their actual costs plus a percentage. They start working with the owner and architect early in the design process. Advocates feel this method provides greater value because the builder gives pricing input and estimates and proposes ways to save money or improve quality before construction begins.

Whatever contract method is used, bidders must craft their proposals carefully to ensure they make money on projects. According to the National Association of Home Builders, the average single-family builder has a net profit margin of 6.4 percent, while residential remodelers typically have a 5.3 percent net profit margin. Those leave little room for error.

Homeowners often hear that they should get at least three bids on their building project, but builders are becoming less willing to prepare competitive bids, especially in relatively stable economic times, because they are very time consuming to compile for a mere shot at a project.

If you are a homeowner, there are some best practices to hiring a custom home builder, and if you are a contractor, there are some best practices to getting hired. The most important is to improve the accuracy of your estimates; frequently, contractors miscalculate the costs of labor, materials, or subcontractors. Invest in estimating software to make this more efficient.

Some ways to improve your estimating skills are to get to know the house with a site visit, study the drawings, and talk to the client to understand their needs.

Also, make sure you consider all costs such as sitework, finishes, HVAC, subcontractors, equipment, materials and overhead, which includes salaries, office rent, vehicles, and other non-job-specific costs of doing business. On average, markup for residential contractors varies widely — anywhere from 10 to 40 percent (around 20 percent is considered average). Markup is the amount of estimated job costs added to the price charged to the customer.

This is different than gross profit, which is customer cost less cost of sales. Michael Stone of Construction Program and Results, Inc. recommends gross margins of 34 to 42 percent on remodeling and 21 to 25 percent on new home construction.

If your business is struggling, you may consider reducing your margin to win more business. Pros advise resisting this at all costs because you could wind up out of business, and trying to make money with fees and change costs over the course of construction will sour customer relationships.

When you are ready to present your residential construction bid, present it in person (rather than via email) so you can walk the customer through it. Explain how you arrived at the estimate, give them the chance to ask questions, go over itemized lists, and finish schedules. Discuss why your costs might vary from other builders.

Government Projects Offer Many Construction Bid Opportunities

Governments at all levels and government-related agencies and bodies such as universities, port authorities, utilities, and transit boards offer a wealth of construction bid opportunities.

Builders find these projects attractive because they range in size, and include many large projects and mega projects with expansive budgets. In the United States, the federal government spent $22.52 billion on construction in 2016, and state and local governments spent $286.03 billion, according to the U.S. Census.

Another attraction of government work is that it fluctuates less with the economy than other kinds of building do. In fact, governments may intentionally launch large public construction projects during economic contractions as a way of supporting the economy and offsetting the loss of jobs. The most famous example in the United States is the New Deal during the Great Depression, when the Public Works Administration built dams, schools, airports, and hospitals through contracts with private construction companies.

While government construction is a good source of bid opportunities, procurement for these projects is highly regulated to ensure the taxpayer is getting the best possible deal and no corruption occurs. In traditional sealed bidding, bidders must follow a highly bureaucratic submission procedure and compile extensive bid documents, which is a time-consuming effort. Failure to follow instructions is likely to disqualify a bid.

“And start early in the bid process. You’re going to need the extra time,” says Seigworth. “Find the right software that won’t require you to create the same documents required on bids over and over again. Never forget that requirements can and do change between agencies on bids that are similar.”

These are several defined formats when governments are seeking to buy construction services. Here are some of the most common acronyms:

- Request for Information (RFI): This is used when the project sponsor needs more information from vendors to define their project and get data on contractor capabilities. There is no assurance that work will be awarded, and further requests are likely.

- Expression of Interest (EOI) or Registration of Interest (ROI): These are similar to RFIs and are often used to shortlist bidders. Contractors express their desire to learn more about the project and potentially be considered. There is generally no contracting decision at the end of this process.

- Request for Quotation or Request for Qualifications (RFQ): A request for quote is the same as an invitation for bid (IFB). This is an opportunity for contractors to bid on a project that is clearly defined, and the buyer evaluates the RFQ primarily on price. This format seeks fewer details on project technicalities and delivery. The result is a commitment from the owner to hire a contractor. Request for qualifications is a pre-qualification stage, and those respondents who successfully pass can move on to the request for proposal (RFP).

- Request for Proposal (RFP) or Request for Offer (RFO): This is a formal and rigorous process. There are usually strict deadlines, forms, and procedures. Governments often seek RFPs through sealed, competitive bidding. RFPs detail how the contractor would execute the project and what the cost would be. An RFP may seek to have the contractor propose ways of handling specific aspects of or problems in the project. There may not be clear specifications.

- Request for Tender (RFT) or Invitation to Tender (ITT): This process is similar in its level of rigor and formality to the RFP, and it is used when the owner has a clearly defined project. The buyer evaluates tenders on both price and qualitative factors.

U.S. Federal Government Construction Bidding

The federal government’s acquisition of design services is covered by the Brooks Act and the Federal Acquisition Regulation that set up a qualifications-based selection method. The General Services Administration has adopted a Design Excellence Program that uses a two-step process to select architects and engineers for public buildings.

For construction acquisition, the federal government sets a prospectus threshold and awards projects below that level through sealed bidding, low-price, technically acceptable competitive proposals, or competitive orders under IDIQ construction contracts discussed above. The lowest responsive (meaning the contractor meets all the requirements of the solicitation), responsible (meaning the bidder is capable and qualified to perform the work) bid gets the job.

U.S. federal government major construction contracts use so-called source selection under federal regulations. These call for technical and price proposals, then best value selection is applied.

To bid on government construction, contractors must register in the System for Award Management and in FedBizOpps. Registration requires information such as your name, address, taxpayer identification name and number, bank routing and account numbers, and your DUNS number. DUNS is a nine-digit identification number for each physical location of your business. You can apply for your DUNS number here.

All federal construction projects with budgets over $100,000 must carry performance and payment bonds. Performance bonds ensure that the contractor will perform its obligations. Payment bonds make sure everyone who supplies labor or materials on the project gets paid.

State, Municipal, and Other Local Public Construction Bids

Government project managers may solicit construction bids for projects ranging from new construction to renovation, electrical work, facilities and structures, roads, and highways to dams, utility infrastructure, airports, hospitals, schools, and ports.

Job order contracting, discussed earlier, is frequently used in government procurement for work that may arise over time, such as repair and renovation.

Each state, municipality, and quasi-governmental agency will have regulations governing its bidding process. Generally these are analogous to federal regulations in terms of keeping the process transparent, competitive, and secure. Government entities may seek to lower the cost of procurement by pooling their purchases through centralized contracting authority, such as a statewide electronic procurement portal. This approach also allows procurement offices to become centers of expertise that create consistency across construction projects, and also ensure fairness.

Government entities also go to great lengths to ensure that all potential bidders have equal access to bid opportunities and information. It is mandatory to post tenders publicly (the preferred way of doing this is through online sites).

Governments use these sites to disseminate project information and avoid meetings or phone calls with bidders, in an effort to prevent the appearance of favoritism or unequal access to information. The stakes are even higher for large, high-profile projects that may be politically controversial.

When sealed bids are opened, procurement officials will disclose all bids including the winner (this is another way to ensure all bidders were treated fairly). These decisions can also be challenged in what is called a bid dispute.

After a contractor receives notice of award, they have a period of time (usually just a few weeks) to sign a contract, and to provide payment, performance bonds, and proof of insurance. Standardized NEC Engineering and Construction Contracts by the Institution of Civil Engineers are often used in the UK, New Zealand, and Australia, among other countries. Once that is in order, the government will issue a notice to proceed with the project.

In addition to other regulations, states and cities may set standards for how contractors must treat workers. This might include how much paid sick and safe time they receive, and demand that contractors pay all workers, companies, and subcontractors on time at the prevailing wage. Similarly, governments may have policies that prioritize hiring or contract award to people in their state or locality, disadvantaged neighborhoods, minorities, the disabled, veterans, and businesses owned by people in these groups.

Many states also have programs intended to support small-scale contractors in their state by making them aware of projects they might be qualified for. For example, Washington state has a small works roster. Licensed contractors can apply to join the roster and win projects with budgets under $300,000.

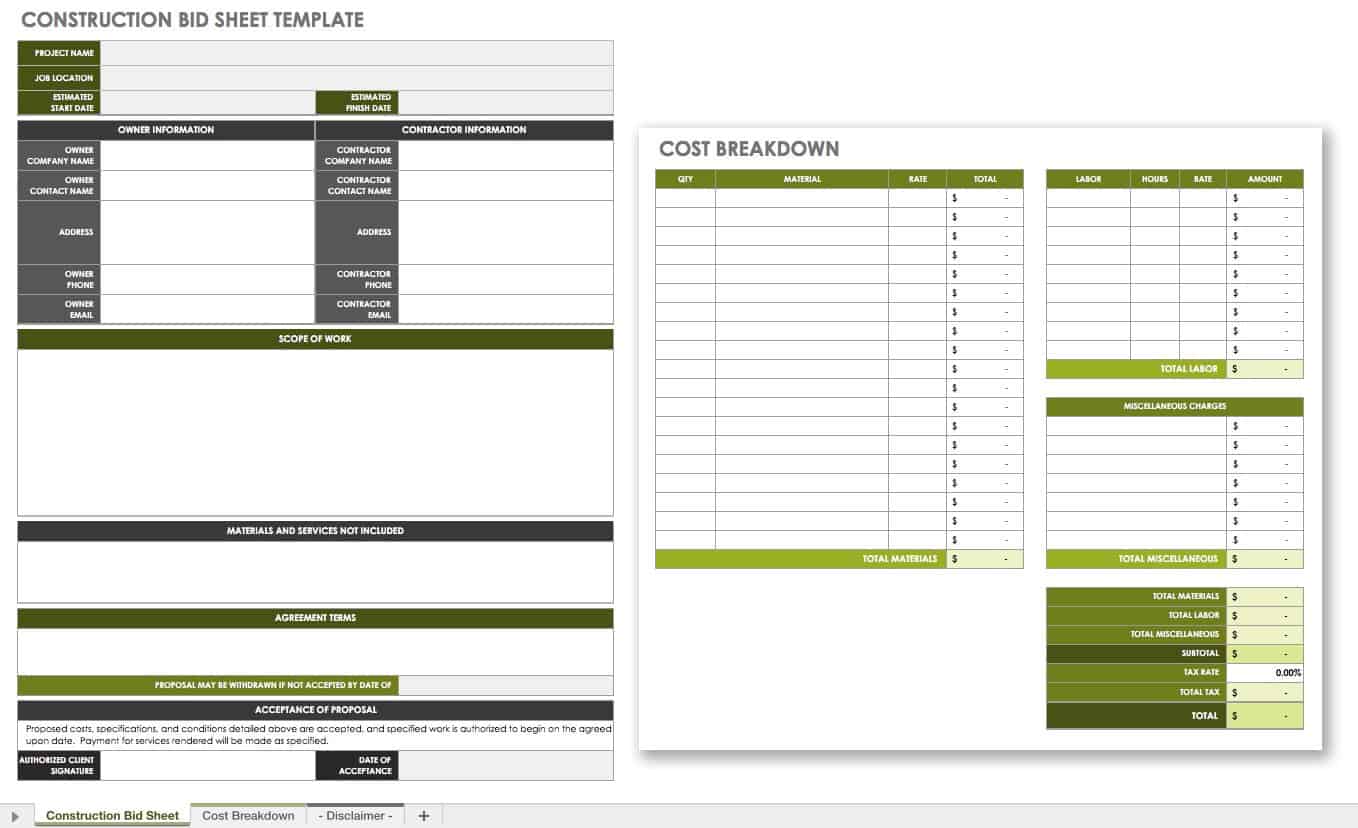

Documenting the Construction Bid

As we have noted, government projects usually require extensive documentation and forms. The same applies to large commercial construction. The smaller the project, the less onerous the project becomes.

All construction bidders are generally required to detail their bid in a document called the bid template, the bid sheet, or the bid form. This specifies the project site and the names of the owner and customer. It gives a project narrative, explains what is not included or is the owner’s responsibility, and sets a completion date and cost. It provides a breakdown of costs, materials, and labor. The owner will sign this to formally accept the proposal.

Download Construction Bid Sheet Template

Technology Changes Construction Bid Preparation

Since their introduction more than 20 years ago, the evolution of construction bidding applications has made the preparation of construction bids much easier. General contractors use these tools for estimating, budgeting, and refining their bids.

“Bid management software helps them manage subcontractor data, monitor communications, share project documents, compare bids, and compile the most complete package for owners. Not to mention, solutions providers often have customer service and success staff who can help companies optimize their bid process on top of implementing the software.”

These solutions automate job costing, which calculates the price of executing a unit of work including labor, materials, and overhead. Therefore, if the contractor knows that installing a sink (including the fixture, labor, overhead and all other expenses) costs a certain amount, and there are 12 sinks in the building, then the the total cost for sinks will be close to 12 times the job cost. He does not need to calculate each one separately unless the sinks are not uniform. You can also define jobs and save them within the software to reuse on future projects.

Usually, these applications come with a database of construction costs. A contractor can subscribe to updates, or receive automatic updates if the solution is cloud-hosted. Construction pros warn that these databases represent national, regional, or state averages, and their data can be inaccurate for an individual project.

Getting a feel for how closely your local costs align with the data is very helpful. Storing your bids within the tool allows you to compare as-built expenses to budget and improve the accuracy of your bids. For example, if you find that your actual costs were about 10 percent higher than database costs in a past project, you can add 10 percent to the averages when budgeting your next job, or use your actual job costs to make projections for a similar future project.

Construction pros cite other advantages of these tools: They reduce the number of errors, centralize your information, and keep data easily accessible by all participants, including those in the field. All members of the team quickly learn about any changes or updates. Using these tools also helps when accepting subcontractor bids.

Benham says that managing subcontractors is a weak point for many general contractors, and he recommends compiling good data and history on subcontractors. “Too often, general contractors don't review a subcontractor's prior history, either with their company or with others, before engaging them on projects,” Benham says.

“Especially for GCs who do not have a structured prequalification process, where subcontractors run through a questionnaire either annually or per project, it can be tough to maintain accurate data on subcontractor performance, compliance, and capabilities. In addition to not having a prequalification process, many contractors still use static spreadsheets and email communication as an ad hoc subcontractor database. Without a centralized, secure, and organized database, general contractors spend hours just sifting through, de-duplicating, and updating their subcontractor contact information before they can even distribute bid information.”

Bidding applications are often part of suites that handle all aspects of construction management including lead generation, scheduling, and accounting.

Tips to Improve Bid Accuracy and Win More Construction Bids

Your success as a construction business depends on many things, but bid accuracy is among the most crucial. Accurate bidding requires you to estimate precisely how much a building will cost to construct in terms of labor and material and have exact indirect and overhead costs.

This knowledge enables you to formulate a bid that is competitive in lowest-bid tenders without pricing your proposal so low that you lose money (which, if the job is big enough or the mistake is repeated over time, could put you out of business).

“Don’t cut corners with respect to bid preparation,” Seigworth urges. “Be methodical with each and every bid; use a ‘cross the T’s and dot the I’s’ approach. It will serve you well.”

Accurate bidding starts with pinpointing your direct and indirect costs and determining your profit. If you want to bid on bonded jobs, bid bonds guarantee the accuracy of your bid, and the surety company will want to see a track record of accurate bidding.

How do you improve the precision of your cost calculations? Construction pros say it all starts with being painstakingly accurate in your construction estimates.

“Consistency in takeoff procedures and cost development practices will yield consistent results. Being organized in tracking the large quantities of information that estimators generate is another important best practice,” Frondorf says.

The level of detail in construction plans and specifications has a big bearing on your ability to be accurate, so get the best possible information from the owner and architect before you start. Also, check the site yourself to understand better what prep work is needed.

“Government owned projects often have stricter specs and require more quality control than other projects, so spec reading is especially critical on these bids,” Frondorf notes.

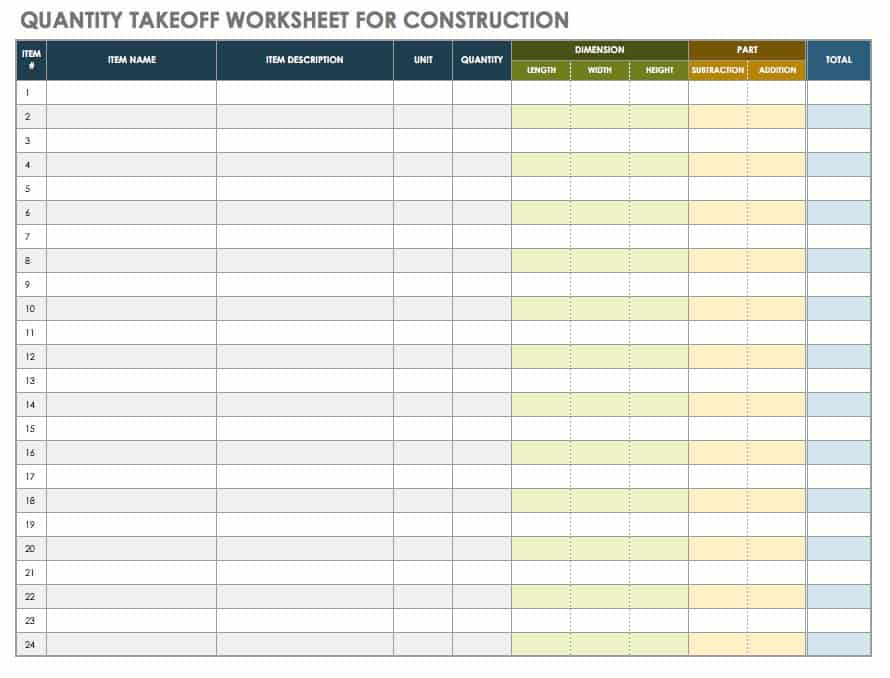

Then prepare your bill of quantities, which is an itemized list of the work and materials required. Creating a bill of quantities is a four-step process that used to be done by hand on paper and is now usually done with spreadsheets or specialized software.

- Taking-Off Quantities: Working from the construction documents, a quantity surveyor will measure the tasks and items of work in a project. This requires scaling dimensions from drawings. One will record these in standard units such as area, volume, or length. For example, you can quantify excavation in cubic meters and steel supports in linear feet. It’s important to follow one of the standard methodologies, such as the New Rules of Measurement. The surveyor will list the number of each item in the project.

- Squaring: Next, the quantity surveyor multiplies the dimensions of the component into square area and multiplies this by the number of times this work item occurs in the construction. This yields the total dimensions, length, volume, and area as applicable.

- Abstracting: Next, the surveyor collects and orders the squared dimensions. Similar tasks and components are grouped together. Once they have taken off and squared all items and have obtained total dimensions, the measurements must be merged. Make deductions for any voids or openings in the building, such as stairs.

- Billing: This last step simply involves presenting item descriptions and quantities in a structured format, the bill of quantities. The surveyor usually presents these in a hierarchy for group, subgroup, and work section. (Examples include substructure, earthwork, and site clearance.)

Download Quantity Takeoff Worksheet

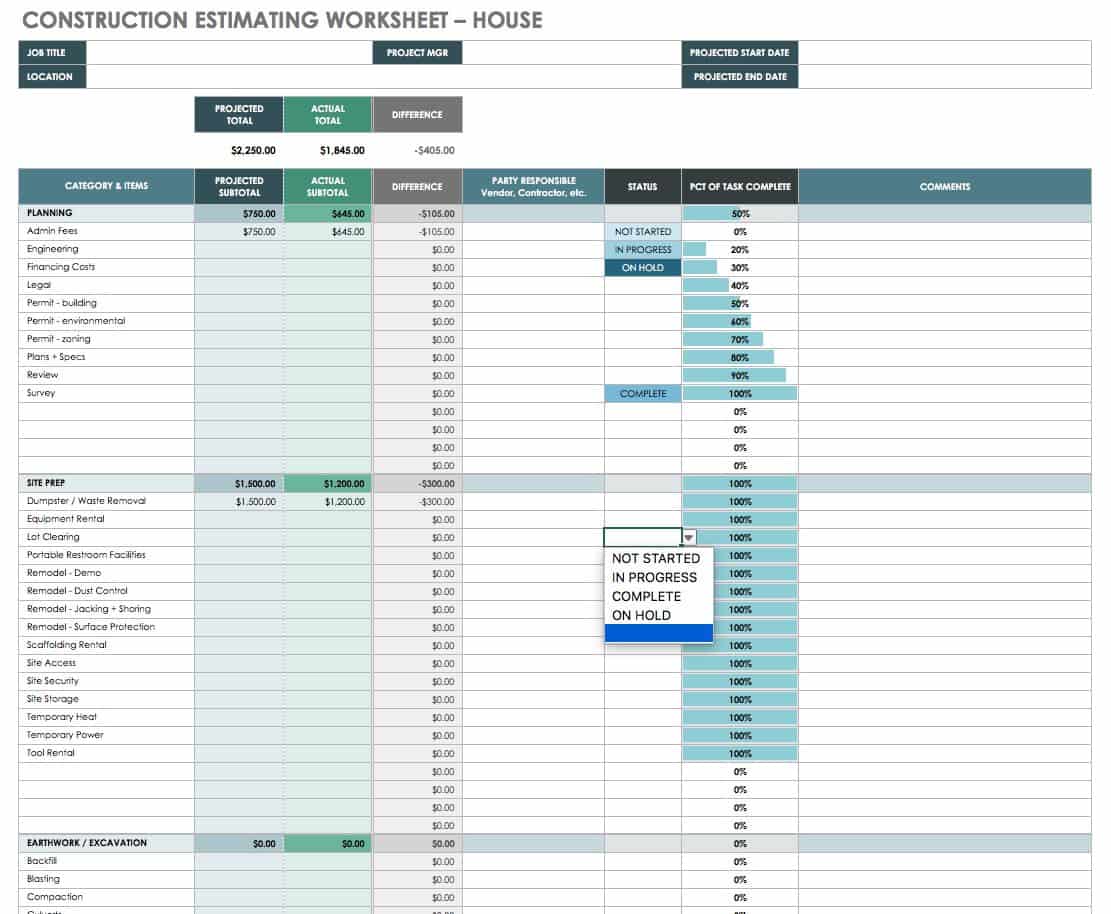

While estimating guides and databases can be helpful, do not rely on them exclusively. Research actual costs in your local area and on your own current and past projects. Realize that costs for materials and labor will fluctuate seasonally and with supply. Use a checklist like the construction estimating worksheet for a house (below) to ensure you don’t overlook any costs. Be sure to include utilities, storage and specialty services.

Consider if any materials are custom, require rush production to meet the project timeline, or require extra handling, as all these factors will increase cost.

Be mindful of project risks and account for them in your bid. For example, if bad weather could delay certain work, factor in the possibility of needing rented equipment longer than anticipated.

Construction Estimating Worksheet for a House - Excel

If you use subcontractors, do not simply accept them or use a cost-plus style contract. Ask for detailed quotes and evaluate them, and seek revisions if you see inaccuracies.

Based on the bill of quantities and your labor costs, you arrive at the direct costs for the job. Your bid will also need to account for indirect costs (the costs of construction not attributable solely to one project). These might include construction project management, contractor supervision, tools and equipment, insurance, depreciation, and more.

Further, you need to factor in overhead or general and administrative expenses. These are incurred whether or not you have active projects and would include office rent, marketing costs, legal, and accounting expenses.

Download Construction Bid Tabulation Template

According to construction pros, here are some of the most common mistakes people make in construction bids:

- Bidding outside your area of expertise (which makes it hard to predict your real-world costs)

- Underestimating overhead costs

- Taking the lowest subcontractor bid without considering quality and expertise

How to Win More of Your Construction Bids

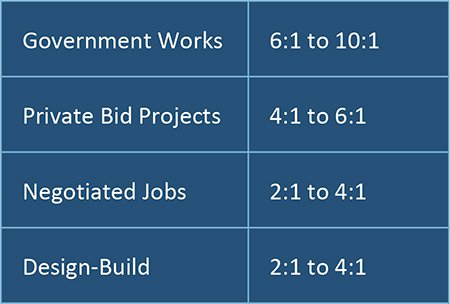

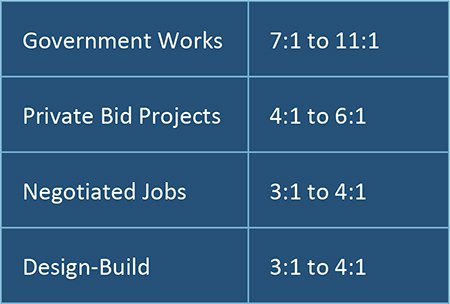

To increase the proportion of bids that you win, start by tracking your winning percentage. This figure is also called your win rate, capture ratio, or your bid-hit ratio.

According to a survey by contractor coach George Hedley, fewer than six percent of construction and design-build companies know and track their ratio.

There is no “right” ratio, although you want it to be as low as possible (a 1:1 ratio would mean you win every bid you submit). Firms that bid on a lot of projects, on highly competitive jobs, or on mostly government work will tend to have higher ratios. Those that focus on negotiated projects generally have lower ratios.

“It’s more important to consistently submit accurate, well developed, and complete bids than to simply have a low bid every time; the jobs that win will have a greater chance of success if their estimates are solid,” Frondorf advises.

According to Hedley, these are reasonable bid-hit ratio ranges for general contractors:

For subcontractors, Hedley looks for these ranges:

You can see patterns by tracking your data. Analyze your win ratio by sector, estimator, geography, size of job, and other metrics. Look for trends in what type of projects you are most likely to win, and focus on bidding more of those projects.

“A general contractor's bid to an owner is only as good as the subcontractor bids it contains,” says Benham. “Subcontractor relationships are crucial to any GC hoping to win a bid. Streamlined, centralized communications on project details and documents creates organization among the chaos of bid day. And subcontractors gravitate towards GCs who share and request information clearly. Securing subcontractor relationships is a big step for any GC, but maintaining those relationships takes time, attention, and great technology tools to aid the communication process.”

Once you know your baseline, start working to improve your ratio:

- Put more effort into your estimates. Fully understand the plans and specifications. Ask questions. Be scrupulous in your measurements and quantity takeoffs.

- Promote your business with a marketing effort focused on your strengths and past accomplishments.

- Bid on projects where you have proven strengths.

- Follow all bidding instructions exactly and fully.

- Employ a personal touch by meeting one-on-one with the decision maker to understand what they are looking for and reflect that in your bid.

- Make your bid memorable. Beyond all the required information, illustrate your outstanding service, quality and expertise: Include testimonials, awards won, training, certifications, pictures, and renderings.

“Know what you’re good at,” recommends Seigworth. “Know the competition. Don’t waste time bidding against too many competitors. Look for an edge and or advantage you may have to exploit making the bid most competitive. Don’t be overly concerned about bidding work outside your area. Often times the competition is too great in your backyard. Go where your competitors don’t or won’t go. I hate clichés, but the saying ‘think outside the box’ is absolutely true.”

95 Sites and Resources for Construction Bid Opportunities

There are many websites that gather construction bidding opportunities so that you can find what you’re looking for. You can locate these sites by utilizing search engines (using keywords like “construction bid opportunities”), or by contacting your local association of contractors.

For example, you may reach out to or browse the sites of the Associated General Contractors of America or the National Association of Home Builders or look into a more local group, such as the Contractors Association of Greater NY or the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties in Washington. You can also search state and local government projects using terms, such as “bid on [state name/specialty, such as schools or roads] construction projects.” University systems and other agencies also tender for construction.

The following are free resources regarding construction bidding:

- Bid Express: This site is free for bidders and hosts bid platforms for agencies, such as Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance, where bid opportunities are posted.

- Building Construction Bid Network: This bid opportunity forum introduces dozens of jobs every day across the world, focusing primarily on the United States and Canada. You can view contact information for key decision makers, learn more about the scope of the work, and link directly to the project or company.

- Construction Bid Source: This site lists bid opportunities in Arizona, Nevada, Washington, California, Oregon, Florida, Texas, Montana, and Utah. Basic project details are available with free membership, while paid memberships offer greater functionality.

- Development Business: This site publishes international bid opportunities for the United Nations and partners, such as the World Bank, and its database allows you to filter by geographic area and project type.

- eBid eXchange: This is a portal that operates procurement platforms for agencies, including Seattle’s construction contracting, Cornell University, Henrico County, Virginia, and the irrigation district of Imperial, California.

- Infrastructure Civil Works and Construction Tenders: This site gathers international construction tenders and is searchable by region and country.

- North America Procurement Council: This hub page links to bid sites for each state. Through this site, you can gain access to over 280,000 combined bid opportunities throughout all 50 states.

- Walsh Construction: Based in Chicago, the company solicits bidders on projects across the United States and in Canada.

The following are paid resources concerning construction bidding:

- Bid Clerk: This site provides detailed information on tens of thousands of construction jobs. Search by sector, project status, and other criteria. You can even search by building use, ranging from daycare centers to golf courses.

- BidNet: BidNet serves a variety of sectors within the realm of construction, including roads, highways, and prefabricated buildings. They search through RFPs each day and send you the ones that best match what you are looking for.

- Bidscope: This site describes itself as a lead search engine for project opportunities, including stored searches and notifications.

- Building Radar: Billed as a real-time search engine for construction sites across the world, Building Radar lets you find bidding opportunities through searches of location, architect, project keyword, and more.

- Construction Data: Specializing in commercial construction, this site includes postings from across the United States. Retail, electrical, and public works projects are available for bidding, among others.

- Construction Journal: This site allows you to access construction opportunities for sectors beyond just commercial and residential, including industrial and manufacturing, medical, laboratory, sewer and water, and more.

- Construction Market Data: This extensive database divides project leads by states and allows you to see bid opportunities, along with bid dates. They currently have billions of dollars’ worth of construction project leads.

- Construction Monitor: This site releases a weekly issue, including thousands of construction projects across the United States covering 68 different markets.

- Construction Wire: You can subscribe to project reports that provide leads based on the criteria you set. You can also get contact and biographical information on point people for the projects you are interested in.

- Dodge Global Network: This site, also a smartphone app, allows you to browse construction projects throughout North America. You can search by keyword and even download construction plans to make sure the project is a good match for you.

- Dodge Lead Center: With the same parent company as the Dodge Global Network, this site focuses on finding you leads in your own state. They estimate having over 2,000 current bid opportunities in California, 1,400 in Florida, and 500 in Massachusetts.

- iSqFt: With over 800,000 construction professionals using their software, this site allows you to see private and public commercial bids in your area. It also allows you to connect with local contractors and manage your bids through your own portal.

- Medical Construction Data: Specializing in medical building construction, this site provides access to over 15,000 projects in various stages. Search by state, project stage, project value, and more.

The following are government resources for construction bidding:

- America’s Business Network: This website is a comprehensive list of bid opportunities, requests for proposals, and more, centering on government agencies. Search by state, scope, and date to find specifics about each project and the agency you’d be constructing for. (Free)

- FedBizOpps.gov: This site by the U.S. federal government’s General Services Administration boasts over 32,000 federal opportunities. You can search by state, keyword, type, and more. Additional features include specific project details and bid requirements, and the ability to “watch” an opportunity. To receive project specifications, you must register in the System for Award Management. (Free)

- Find RFP: This site gathers and screens government bid opportunities throughout the U.S. and sends you notifications. (Paid)

- Government Contracts and Bids: This site, which has over 34,000 active government bids, allows you to narrow your search to construction jobs and see bid opportunities across the United States. (Paid)

- GovernmentBids.com: This subscription site lists 35,000 construction bid opportunities a month from state, local, and federal government agencies in more than 200 industry classifications. You can search by state or region and specialty, such as roads. (Paid)

- State and Federal Bids: This site specializes in government road and bridge construction projects. They have information on road and bridge-related bids from over 17,000 government agencies and also cover construction related to jails, universities, and airports. (Paid)

- Onvia.com: This site lists tens of thousands of near-term government projects. The company was recently acquired by Deltek, so its offerings may evolve. (Paid)

The following are regional resources for construction bids:

- California Construction Bid Opportunities List: While this site does not list tenders themselves, it has links to state, local, and regional opportunities throughout California, including school districts. (Free)

- City of San Diego: This site provides hundreds of construction jobs throughout San Diego and surrounding areas. Search by region, project type, and more. (Free)

- Merx: This site lists public and private construction opportunities across Canada, including agencies, crown corporations, and private construction projects. It also lists U.S. opportunities that are open to Canadian bidders. (Paid)

- PlanHub: Cloud based application that allows general contractors to share project files and information with subcontractors. (Free)

- IHC Construction Companies LLC: This contracting company’s site offers bid opportunities throughout the state of Illinois. The site divides openings into subcategories, like construction management and general contract. (Free)

- Infrastructure Civil Works and Construction Tenders: If you live outside of the United States — or are simply looking for work in these areas — this site divides up projects by countries all over the world. From Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, take a look at local projects and learn details about each opportunity by subcategory. (Paid)

- Miron Construction: For subcontractors looking for work in the Midwest, Miron Construction has tons of bid opportunities throughout Wisconsin, Iowa, Michigan, and more. They have dates and descriptions of each bid, along with what the exact project is and where it is located. (Free)

- Universal Information Services: This site gathers construction leads and bids from 400 media sources across the Midwest. (Paid)

- DASNY: DASNY provides construction services throughout the state of New York and lists a variety of bid opportunities on their board. Not only can you view project details, you can also view a list of interested subcontractors and suppliers as well as project estimates and notices. (Free)

- Daily Journal of Commerce: For over 100 years, the Daily Journal of Commerce has been providing information and opportunities for business and construction. The site centers on the Pacific Northwest and includes construction bidding opportunities through a variety of subcategories. (Paid)

- Contractor Plan Center: This site has information on projects in Oregon and Washington, as well as some projects in Alaska, Idaho, Montana, and Northern California. (Paid)

- Bids PR: Updated daily, this site centers on bid opportunities throughout Puerto Rico and other parts of the Caribbean. The site tracks and reports procurement activity for the bids you are interested in. (Paid)

- LDI Line: Calling themselves “the largest free online plan room in the Southeast,” this site is updated daily to provide current project leads throughout the Southeastern United States. In addition to seeing dates and logistical information, you can order hard copies and digital plans for each project. (Free)

- Texas Parks and Wildlife: The country’s second-biggest state has dozens of construction bid opportunities available on any given day. In addition to getting extensive information on each project, you can even download a PDF of construction contracting periods and the estimated budgets for every available project. (Free)

The following are state resources for construction bids:

State procurement offices often award construction contracts. To be ready to bid on these opportunities, find your state procurement page and create an account to get notified about new construction contract opportunities.

- Alabama: Division of Purchasing

- Alaska: Vendor Self Services

- Arizona: Arizona Procurement Office

- Arkansas: Department of Finance and Administration

- California: Procurement Division

- Colorado: ColoradoBIDS

- Connecticut: Department of Administrative Services Contracting Portal

- Delaware: State Procurement Portal

- District of Columbia: Office of Contracting and Procurement

- Florida: Division of State Purchasing

- Georgia: Department of Administrative Services

- Hawaii: State Procurement Office

- Idaho: Department of Administration - Purchasing

- Illinois: Procurement Services

- Indiana: Department of Administration

- Iowa: Procurement and Bidding Opportunities

- Kansas: Bid Solicitations

- Kentucky: Purchasing and Procurement

- Louisiana: Office of State Procurement

- Maine: Division of Contract Management

- Maryland: Department of General Services

- Massachusetts: Operational Services Division

- Michigan: DTMB Central Procurement

- Minnesota: Department of Administration

- Mississippi: Procurement Search

- Missouri: Division of Purchasing, Bidding, and Contracts

- Montana: State Procurement Bureau

- Nebraska: Department of Administrative Services - Bid Opportunities

- Nevada: Purchasing Division

- New Hampshire: Bidding Opportunities

- New Jersey: Division of Procurement Bid Openings

- New Mexico: State Purchasing Division

- New York: Procurement - Bid Openings

- North Carolina: Interactive Purchasing System

- North Dakota: Bidder Resources

- Ohio: Procurement for Suppliers

- Oklahoma: Central Purchasing

- Oregon: Procurement Services

- Pennsylvania: eMarketplace

- Rhode Island: Division of Purchases

- South Carolina: Procurement Services

- South Dakota: Bureau of Administration Advertisements for Bids

- Tennessee: Central Procurement Office

- Texas: State Purchasing

- Utah: Division of Purchasing

- Vermont: Office of Purchasing and Contracting

- Virginia: eProcurement Portal

- Washington: Department of Enterprise Services

- West Virginia: Purchasing Division

- Wisconsin: VendorNet System

- Wyoming: Procurement and Purchasing

Useful Construction Bidding Sites

The Balance’s article, "How to Subscribe to Bid Events," takes you through the process of subscribing to bid events and allows you to keep track of upcoming bids and bidding requirements.

The document Introduction to Government Agency Bids, put together by the North America Procurement Council, takes you step by step through what a government agency is, how they conduct business, how bids work with a government agency, and more.

Key Terms in Construction Bidding

Best Value Method: The best value method involves evaluating and ranking contractors based on their bids and qualifications, and assessing who is the most qualified for the best price.

Bid: A bid is a proposal to undertake a construction project or an aspect of the construction project.

Bid Package: A bid package is a portfolio of documents, including estimates, drawings, and specifications, that one submits for consideration for a construction project.

Bid Solicitation: A bid solicitation is contact, generally through a letter or email, to notify qualified bidders of the opportunity to bid on a construction project.

Bill of Quantities: A bill of quantities is an itemized document that lays out the costs of each component of a construction project.

Cost plus: This is a contract in which the buyer agrees to pay for all supplies and labor, as well as an additional amount for contractor profit.

Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP): A GMP is a contract in which you set a ceiling for how much the owner will pay (unless there is a change in project scope).

Hard Bid/Fixed Price/Stipulated Lump Sum: This is a contract in which the contractor agrees to one total sum for all components of the project. You generally use this type of contract for projects that have well-defined costs and components.

Lease Leaseback: This is a contract in which the owner sells the property and then leases it from the purchaser.

Percentage of Construction: This is a less common form of contract in which the compensation is based on a percentage of construction costs.

Time and Material: This is a contract in which you agree upon a price based on the time involved and materials you use for the project.

Unit Price: This is a contract in which you determine the final cost based on the unit prices of materials.

Contractor: A contractor is a company or person that signs a contract to provide construction services, generally concerning labor or materials.

Cost Reimbursement/Cost-plus Contract: This is a contract in which the agency provides funds beyond those required for materials so that the construction company or contractor can make a profit.

CSI Code/MasterFormat: CSI (Construction Standards Institute) publishes MasterFormat, a publication that provides standards for construction projects. It includes detailed numbers, cost information, requirements, and specifications for most construction and building design projects within North America.

Design-Bid-Build (DBB): Also called design-tender, this is a method in which the architect creates a detailed design of the project that they then present to potential contractors. The contractors then bid on the project and must construct the building according to this design and its specifications.

Design-Build (D-B): Design-build is a process you use primarily for residential construction, in which you don’t involve an architect in the initial design plans. D-B uses one single contractor or builder for the entire construction process, which allows for more flexibility than design-bid-build.

Design Excellence Program: Created by the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), the Design Excellence Program provides a streamlined selection process of top-ranked architects and engineers. Professionals in the private sector who use these contractors can also provide feedback for their peers.

Estimate: An estimate is a process through which you project the cost of supplies and labor.

Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ): An indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contract (IDIQ contract) is a government contract that allows for an unlimited quantity of services or supplies during a set amount of time.

Job Order Contracting: A type of contract with no set quantities that allows for multiple projects to be completed through a single contract. This contract allows for faster procurement time while eliminating a typical bidding cycle.

Payment Bonds: Contractors put up payment bonds as assurance that their suppliers, laborers, and subcontractors will be paid.

Performance Bonds: Performance bonds provide assurance that the contractor will meet their end of the contract agreement. Usually posted by a bank or insurance company, the contractor must put up some form of collateral.

Preconstruction Services vs. Construction Services: Preconstruction services are the services that a contractor offers before the project officially begins. These can include deliverables, such as project scopes, risk analyses, execution plans, and more. Construction services are the usual services that take place after the commencement of the project.

Prime Contractors: Also known as main contractors, these are the key people or companies that agree to complete the contract. A prime contractor has the authority to hire subcontractors to complete particular parts of the associated contract.

Procurement: A process through which one sources and evaluates all materials, potentially making a purchase.

Prospectus Level: A prospectus level is a dollar amount that the federal government sets for a project.

Rebid: A rebid occurs when an owner doesn’t choose any bid due to a discrepancy in expectations between said owner and the bidders. At this point, the owner must change the scope of the bid. This part of the process is referred to as the rebidding process.

Request for Proposal (RFP): An RFP is a solicitation by a company or agency to prospective contractors or suppliers. It is a company’s way of letting contractors or suppliers know that they are open for proposals for their project.

Scope of Work (SOW): A scope of work is a detailed description of the work that one must complete under the contract. Generally, SOWs are extremely detailed, including designs, materials, deadlines, special considerations, etc. for each aspect of the project.

Sealed Bidding: Sealed bidding is a process in which all prospective contractors (bidders) submit their bids without knowing what the other bidders have submitted.

Source Selection Method: A source selection method is a negotiation process-oriented strategy that agencies use to choose the proposal that best meets their goals. Each company creates their own evaluation plan, which they must follow throughout source selection.

Statement of Work: An official document that outlines all tasks, schedules, deliverables, and activities associated with a project. This document often serves as part of the contract.

Subcontractor: An individual or company that signs a contract to take on a portion of a larger contract.

Two-Step Bidding: This is a process that assesses proposals. The first step is the submission of technical proposals that meet contractors’ set requirements. The second step is the invitation of qualified contractors to provide a bid. It is also referred to as sealed bidding.

Working Drawings: Also known as blueprints or construction drawings, working drawings are sketches, drawn to scale, that serve as a guide for a construction project. These can include information on framing, floor plans, elevation, and more.

Improve Construction Bidding with Smartsheet for Construction

From pre-construction to project closeout, keep all stakeholders in the loop with real-time collaboration and automated updates so you can make better, more informed decisions, all while landing your projects on time and within budget.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.