What Is a Team? Teams vs. Groups

Anyone who’s worked with a group of other people to achieve something must know something about teamwork. Right? Maybe. While all teams are groups of people, not all groups of people are teams. And not all teams are created equal. In this section, you’ll learn some key concepts concerning teamworking: definitions, benefits, core processes. and major team types.

A team is a group of people organized to achieve a goal, and teamwork in its most basic form is cooperation among team members. But true teams are shaped by a more complex set of attitudes and practices. First is team composition. Effective teams have members who complement each other’s strengths and compensate for each other’s weaknesses. So, synergy — the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts — is a key part of teamworking. Second, effective teamworking requires a certain mindset, a willingness among team members to put the interests of the team above their own. Third, a well-run team needs a clear mandate, strong leadership, and sound processes.

While these ideas are simple in theory, they’re extremely challenging to achieve in practice.

As anyone who has worked on team projects at school or at work knows, it’s far more common to find yourself in a bad team than in a good one.

That said, we humans love working with and even watching good teams. Psychologists have identified a fundamental human need to feel a sense of belonging, and teams provide that. Our success as a species has depended on our ability to cooperate and work in teams. From the primitive hunting party to the finely tuned coordination of surgeons in an operating room, strong teamwork is a harbinger of success.

In daily life, most people will encounter teams at work, whether in an office or on the factory floor. Business projects are case studies for working together as a team. You may also find yourself involved in teamworking in group projects at school or on boards and committees for volunteer causes.

Looking for ways to keep your remote workforce connected?

Download our latest ebook to discover the top 10 helpful tips to establish and maintain company culture across your distributed teams.

Why Teamwork Is More Important Than Ever Before

These days, teamworking is becoming more important. In the corporate world, this phenomenon reflects a few trends:

- Organizations are becoming less hierarchical, and teamworking is taking the place of top-down management strategies in many contexts.

- Increased competition in the marketplace is forcing companies to strengthen their innovation, responsiveness, flexibility, efficiency, quality, and customer satisfaction, and all of these qualities require good teamwork.

- The rising complexity of many fields is leading companies to recruit staff whose skills are more specialized. This trend, in turn, is creating a need for interdisciplinary participation in projects, which employees commonly achieve through teamwork.

- Research has shown that organizations where teams work well together often have superior performance because successful collaboration deters sabotaging behaviors, such as withholding useful information, spreading negative rumors, or undermining others.

- Organizations are leaner than ever after the financial crisis of 2008 prompted extreme cost cutting. This economizing has been accompanied by cultural shifts in which companies are requiring self-managing teams and seeking to promote a wide sense of ownership.

Teamworking offers advantages to organizations because teams combine a diversity of skills and personalities. Collaborative approaches built on different perspectives and skillsets tend to be more effective than those created by individuals or overly homogenous groups. Teamworking, when done well, can lead to better problem solving, greater creativity, increased morale, and reduced risk.

On the downside, management often tasks teams with important projects, so when they fail, the consequences can be far reaching in terms of money, time, and opportunity. Poor teamwork can lead to bad decisions, missed opportunities, and wasted time in meetings, not to mention interpersonal hostility and unhappy workplaces.

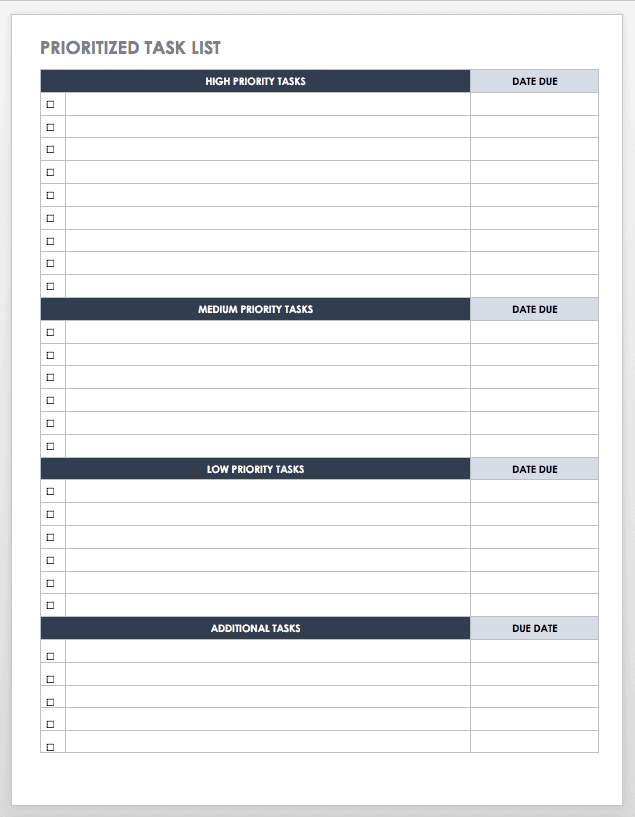

To help your team reduce wasted time in meetings and stay organized, try this team task list template.

Use Team Task List by Priority Smartsheet Template

From an employer’s perspective, good teamwork rewards team members with high-quality relationships, improved morale, and a sense of ownership in the organization, which then improves performance and employee retention.

Nevertheless, building and sustaining a good team is anything but easy. In sports, managers, coaches, and fans agonize over the best possible combinations of players. It’s similar in the work world. As with sports, business team managers find that even highly skilled people may not make the cut if someone else offers more value to the team because of particular personal qualities or experience. Plus, it’s worth remembering that even a team that looks great on paper may fail if it lacks esprit de corps, the force that binds teammates via loyalty, relationships, and a shared sense of purpose.

In modern businesses, there are a few main types of teams as well as core processes that constitute teamwork.

- Top Management Team: An organization’s top management team, abbreviated as the TMT, usually comprises its most senior managers. By virtue of its members’ seniority, a TMT is typically highly autonomous. The TMT oversees organizational functions at the highest level, such as defining an organization’s goals, creating and implementing strategies to achieve these goals, and assessing progress toward goals. Since a TMT comprises representatives from an organization’s main functional areas, the team lead must clearly define the TMT’s purpose and objectives to ensure that its members are all speaking the same language and focused on the same issues. As such, the information flow between an organization’s main functional areas goes a long way to facilitating the work of its top management team.

- Action Team: An action team, also referred to as a swift-starting team, is assembled on an ad hoc basis to fulfill a specific function. An action team’s work is by nature dynamic and reflexive, and its membership, which typically includes a number of subject specialists, is likely to change frequently. This means that effective coordination of efforts is critical, especially since action teams in certain industries, such as healthcare, work under tremendous pressure. Generally, there is not much focus on team-building activities and the chance to develop the personal relationships or familiarity that facilitate effective teamwork. As such, research into action teams suggests that those demonstrating more predictability, coordination, and better information-sharing practices from the outset tend to be more effective.

- Virtual and Remote Team: A virtual team uses communication technologies to collaborate and perform its functions. Virtual teams aren’t necessarily separated by geography or time. They can exist within organizations in the same physical location, if they comprise individuals who don’t actually work with one another directly. Virtual teams are popular because they allow organizations to coordinate talent without being constrained by geography. However, some aspects of virtual teamwork, such as the lack of personal interaction and asynchronous flow of information, can make it more difficult to achieve goals than it would be for teams who work in physical proximity to each other. In addition, the lack of in-person interaction may negatively affect a virtual team’s sense of loyalty and shared purpose as well as its morale and chemistry.

Regardless of which type of team is operating, the activities will fall into three main categories, classified by researchers as action processes, transition processes, and interpersonal processes.

Action processes involve the actual pursuit of goals and the monitoring and regulation of team behavior and performance to meet these goals. Transition processes, which occur between periods of action, involve identifying new goals and determining courses of action to meet these goals. Interpersonal processes relate to the management of team members, including conflict resolution, team building, assigning roles, and similar functions.

Toxic Teams: Many of Us Dislike Teamworking

We know that employers prize teamwork. In the 2016 Bloomberg Job Skills Report, 56 percent of recruiters across all industries said “working collaboratively” was one of the five most important job skills. In the National Association of Colleges and Employers' Job Outlook 2016 Survey, nearly eight in 10 employers said they checked new graduates’ resumes for evidence of the ability to work in teams, making it the second most sought-after attribute.

Here’s an interesting paradox about teamwork in the workplace: Despite how important it is for professional success, many people dislike working in teams. One University of Phoenix study found that three-quarters of employees would rather work on their own, even though 95 percent of people who have worked on teams believe teamworking is critical in the workplace.

The three primary reasons for the aversion to teamwork lie in the nature of the person, the nature of the work, and the nature of the team.

At the individual level, it’s often introverts who find themselves disinclined to work with teams. Introverts feel easily drained by what they perceive as an overload of social interactions, and if they don’t get enough time to themselves to recharge, they’re likely to find teamwork exhausting and ultimately unpleasant. This can be compounded by the fact that extroverts, who make up the majority of the population, tend to influence team activities more than introverts do, thus creating hyper-social team environments that reward interaction-hungry extroverts but tax introverts. Of course, good teams need both personality types, and the fix may be as simple as introverts making sure they get their time alone, and team leaders allowing introverts to interact on their own terms.

Moreover, some types of work are not well suited to team efforts, and an attempt to force unnecessary collaboration on employees can result in unhappy team members and poor results. You’re most likely to see this scenario with creative endeavors.

Team dynamics are the third major reason people dislike teamworking. The survey cited above found that 70 percent of employees said they had been part of a dysfunctional team, 40 percent had seen verbal confrontations among team members, and 15 percent had witnesses physical fights.

Negativity in teams often starts with competitiveness among the members. A lack of accountability that allows some team members to get a free ride can also be frustrating, as can unfair or unequal divisions of labor within a team. If members of teams feel held back by their teammates, morale may sink. Poor communication can cripple a team’s efficiency. Weak leadership can lead to feelings of wasted effort and pessimism, setting the team on a downward course.

What Makes a Team Player? Key Skills for Teamworking

These problems can be avoided in part by picking individuals with a strong capacity for teamwork. These “team players” are committed to the team’s purpose, willing to accept responsibility, and reliable. They’re confident and assertive when working in groups, they’re proven problem-solvers, and they’re willing to be flexible. Moreover, they’re usually strong communicators with the ability to give and take constructive criticism, and they are supportive of teammates. You can find a comprehensive list of team skills here (which are valued by employers).

Skills of the Team Player

- Confident within a group

- Contribute ideas effectively

- Shares responsability

- Communicates effectively

- Flexible

- Committed to the team

- Problem Solver

- Appropriately assertive

- Learns from constructive criticism

- Gives useful feedback

- Reliable

- Listens actively

Source: University of Kent

If you’re wondering how much of a team player you are, try this self-assessment survey.

Research into teams suggests that members of teams can be broadly categorized as either task-focused or process-focused individuals. (Process-focused is sometimes called relationship-focused.)

Task-focused team members and leaders prioritize the accomplishment of goals. They stress the importance of effective organization and time management, and they’re objective decision makers.

Process-focused team members and leaders prioritize interpersonal relationships and team welfare, and they emphasize the importance of communication, team building, and conflict resolution.

Both approaches have their pros and cons. Task-focused leaders excel at performing tasks and solving problems effectively and on deadline, and they’re critical to an organization’s bottom line. However, they’re also likely to be seen as indifferent and lacking in empathy. They’re more likely to be poor people managers over the long term, and they may struggle to recognize and deal with interpersonal issues within teams.

Alternatively, process-focused leaders excel at keeping teams happy and functional, and they’re usually more popular with their teammates. However, they’re prone to missing deadlines and failing to meet objectives, and the standard of their teams’ work can be more inconsistent than that of teams run by task-focused leaders.

Since these approaches in essence are different paradigm views on how the world should be run, it’s difficult — and perhaps impossible — for a task-focused leader to transform into a process-focused leader or vice versa.

But it’s not necessary to go that far. A task-focused leader can become a much more effective manager over the long term by making a point of caring for their teammates’ welfare, supporting them, and making an effort to develop interpersonal relationships. One way to win team members’ hearts is to make sure you record and respect their vacation plans. Try this team vacation planner template.

Download Team Vacation Planner Template

Excel | Word | PDF | Smartsheet

Similarly, a process-focused leader can fulfill their responsibilities better by keeping sight of a team’s objectives and balancing an innate concern for teammates with a commitment to delivering a team’s goals effectively and on time. Some teams seek to strike this balance by splitting leadership duties between task and process-focused leaders.

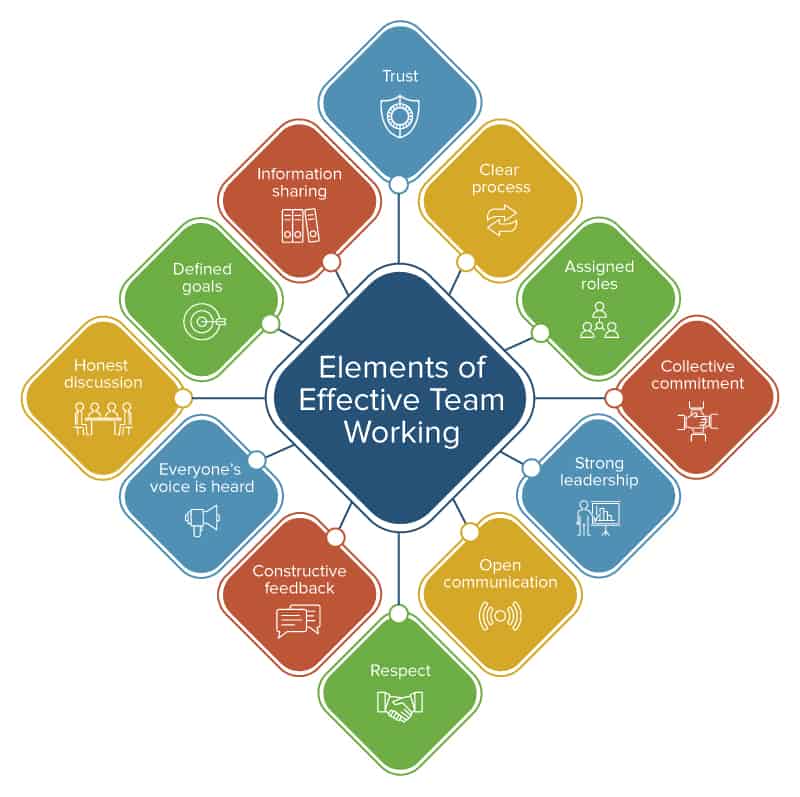

How to Be an Effective Team Member: The Hallmarks of Effective Teamworking

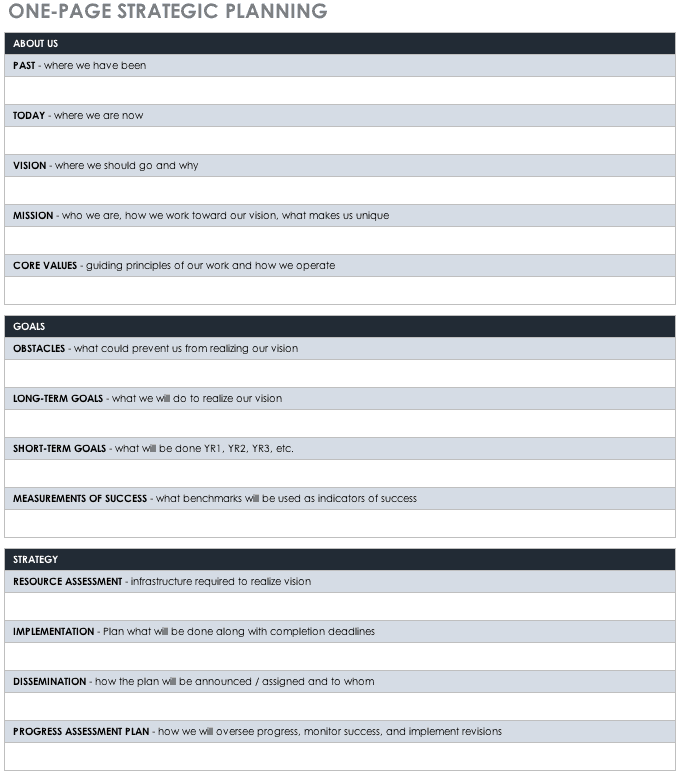

Organizational leaders, team leaders, and team members need to share a common standard of what constitutes effective teamworking if a company wants consistently successful teams. The process of identifying your model of an effective team is something to explore within your organization’s general culture-building work. You may find it helpful to develop a strategic plan and strategic vision for your team.

Download One-Page Strategic Planning Template

Excel | Word | Smartsheet

Download Strategic Vision Template - Excel

What are the most frequently cited hallmarks of effective teamworking and how do these compare to ineffective teams?

- Effective teams are good at setting goals and then creating (and sticking to) a process, schedule, or framework to meet these goals by a deadline. They’re good at coordinating their efforts and assigning responsibility so that everyone knows what they’re doing and why it’s important to the task at hand.

- Ineffective teams, on the other hand, don’t set clear goals and don’t outline a clear path to meet these goals. Since they don’t know what their goals are, they typically struggle to assign roles and responsibilities. As a result, there’s confusion about what people are supposed to be doing and why it’s important.

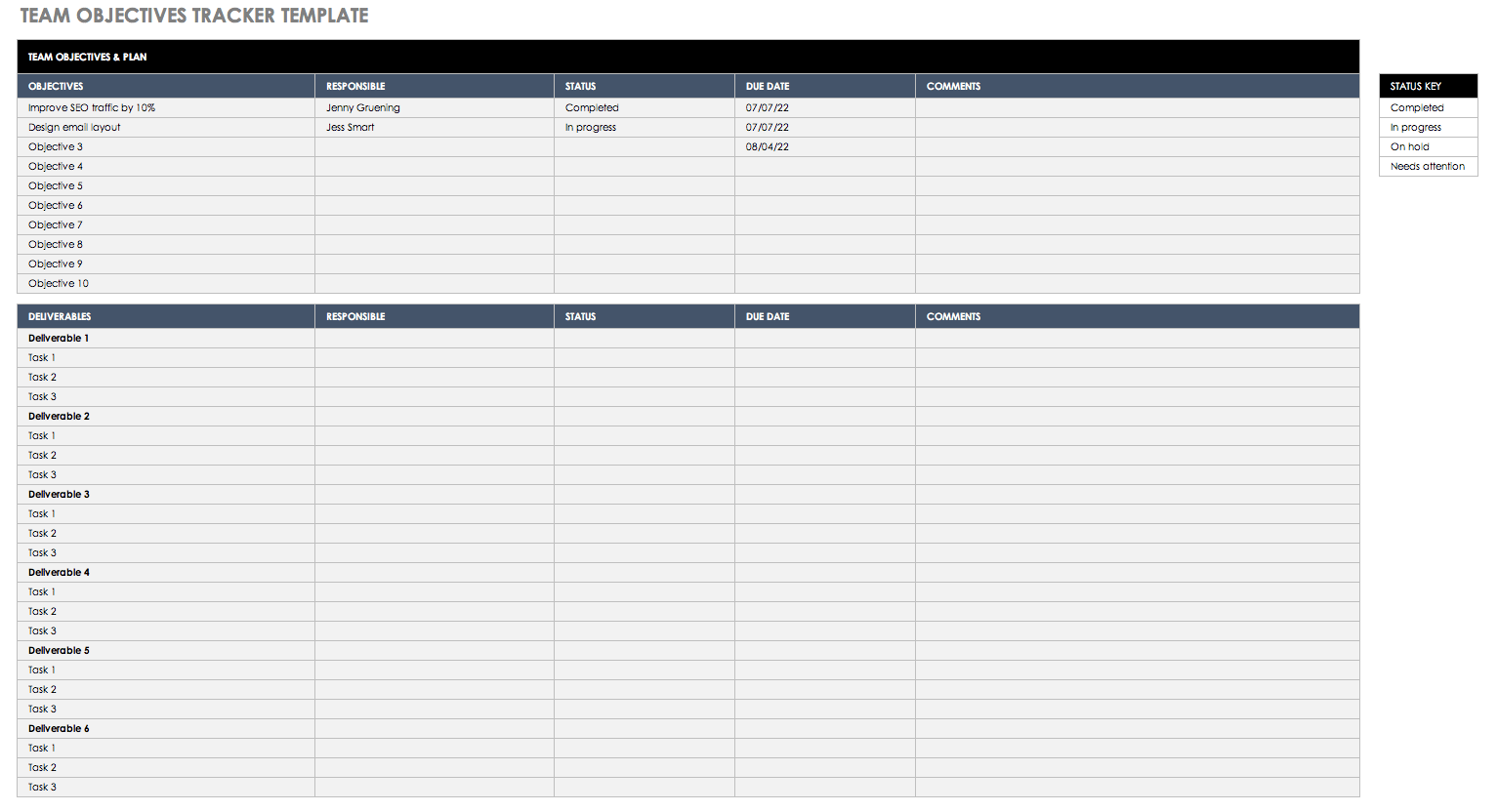

Try using a scorecard to track team progress on key objectives.

Download Team Objectives Tracker Template

Creating an action plan that outlines the tasks needed to accomplish your goals is another helpful way to make the work visible. Try this template to map out and meet team goals.

Download Action Plan Template

- Effective teams are also characterized by a healthy respect for what each member can contribute, encouraging broad participation and lots of open discussion. It’s equally crucial to foster an atmosphere that supports participation and discussion, constructive criticism, and the recognition of the significance of disagreement. Respecting the synthesis of ideas is also a must.

- Ineffective teams, on the other hand, are typically dominated by a small number of team members, resulting in the inequitable evaluation of team members and their input. Managers ignore some perspectives and put down certain team members, which can quickly decrease morale, breed dissatisfaction, and defeat the whole purpose of building a team, i.e. to gain multiple perspectives.

- An effective team whose members recognize and appreciate each other’s contributions to the team’s goals will fulfill its responsibilities in a spirit of trust and mutual cooperation.

- A team whose members are not aligned, because of a lack of clarity and respect for individual contributions, will struggle with a lack of camaraderie and a general inability to work together effectively.

- An increased buy-in to the team purpose and a positive sense of membership correlates positively with social laboring, a phenomenon in which people work harder as part of a group than they would as individuals.

- Conversely, a lack of camaraderie and little sense of team purpose contribute to social loafing, in which individuals expend less effort as part of a group than they would as individuals. The concept draws from the so-called Ringelmann effect, named after Maximilien Ringelmann, a French agricultural engineer who, in 1913, found that the more people who pulled on a rope, the less effort each individual contributed.

The Manager’s Role in Creating Teams That Work

A manager’s work in building and leading a team is critical to the team’s success. We’ve already talked about the need to strike a balance between task-based and process-based leadership. So, here’s a handful of basic team-building principles that take from both leadership approaches.

- Get the Right Balance of People: A good team has members who complement each other’s skills and compensate for each other’s weaknesses. When building a team, a manager should think about the work that the team will perform and select individuals with well-suited skillsets. But, striking the right balance of individuals depends on more than their skills. For one, it’s important to be certain that the individuals work well as part of a team. This isn’t a question of whether the people like each other. Past history, flexibility, and stress response are important considerations. It’s vital to give team members ongoing feedback about their performances and continue to develop their skills with training.

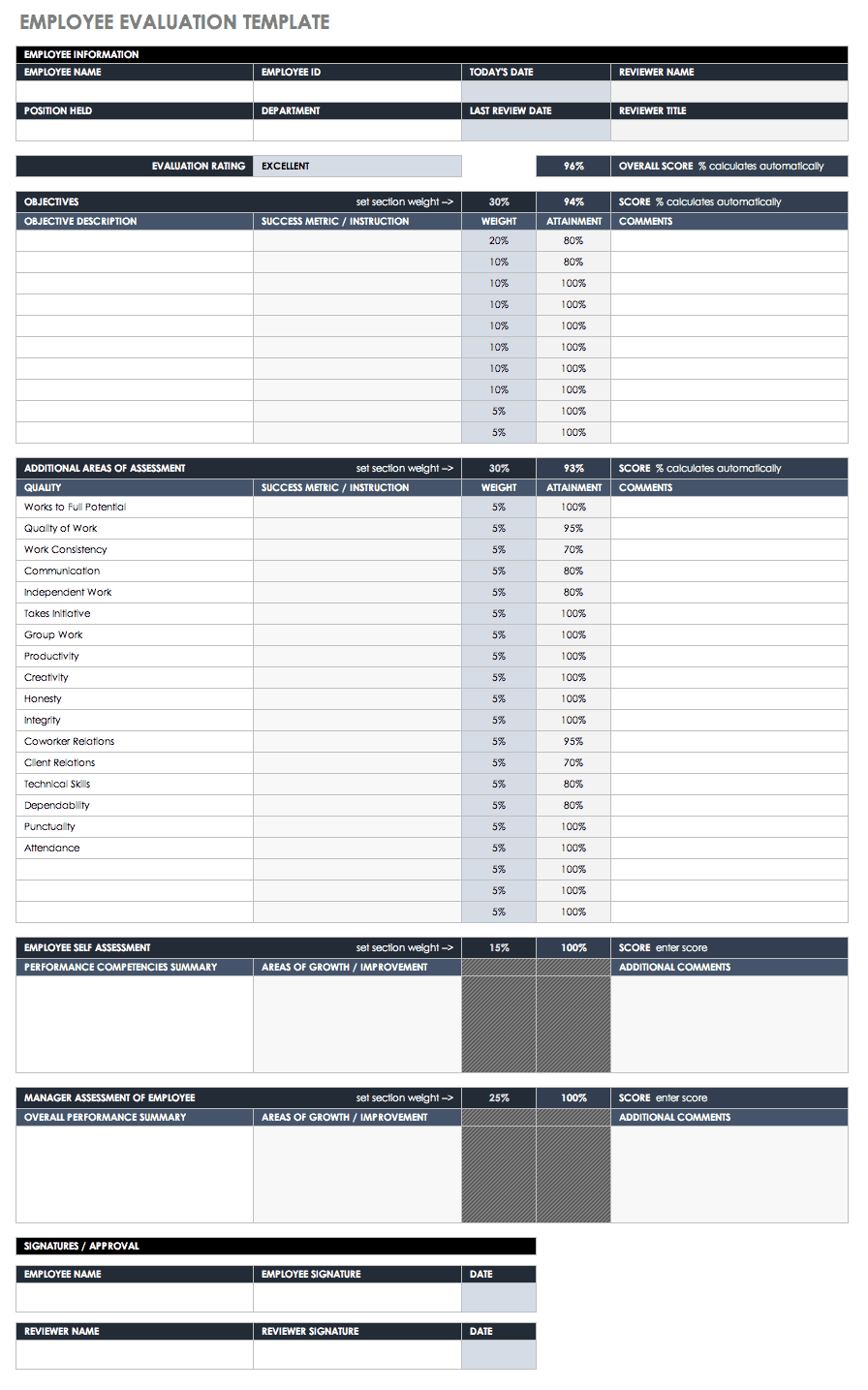

Download Employee Evaluation Form Template

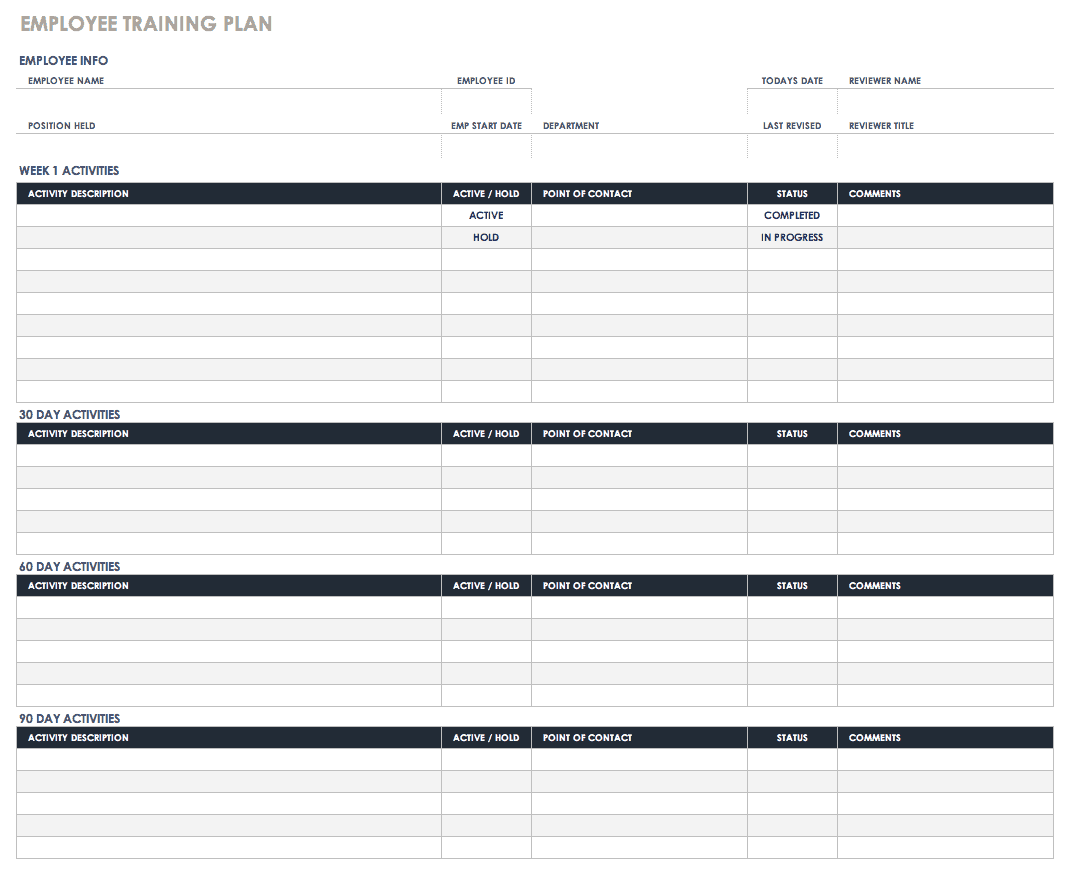

Download Employee Training Plan Template

Excel | Word | PDF | Smartsheet

- Create the Right Organizational Framework: Any team’s core function and purpose must align with the organization’s mission, though this is a frequently overlooked aspect of team building. Just as employees who buy into an organization’s mission tend to be effective, people who buy into a team’s purpose make better team members and teammates. (Remember the phenomenon of social laboring?) It’s also a good idea to reward teamwork and incentivize good performance. You can do this in a number of ways depending on the nature of your organization and team, from free food to financial payoffs. Rewards for teamwork and good performance can double as team-building activities. A team dinner is both a good reward for completed work and a way to bond. Similarly, organizations may choose to invest in team training, an exercise which a 2008 study showed could improve team outcomes. Finally, most teams will need to agree upon and establish a set of ground rules for working and assessing performance. A team leader and/or an external supervisor usually enforces these rules.

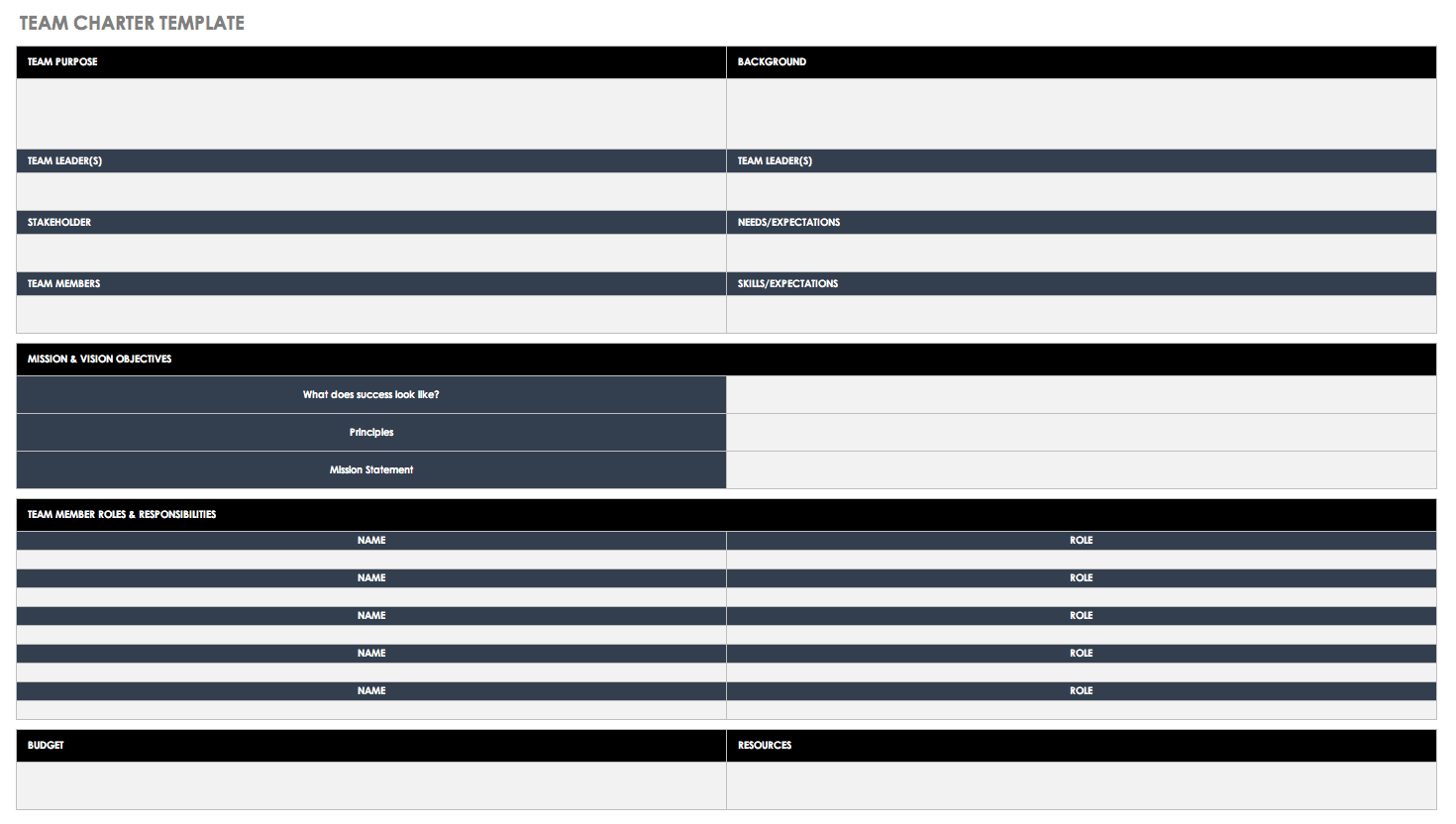

Creating a team charter is a great way to get buy-in from members and focus your energies.

Download Team Charter Template

- Provide Good Leadership: Teams are typically interdisciplinary, but they also benefit from having a leader who drives the processes of setting and meeting goals, coordinates and monitors team members’ responsibilities and performance, and takes the lead in conflict resolution. A team that is prone to being pulled in a number of different directions will also benefit from an experienced leader’s judgment. (It’s imperative that a team trusts its own judgment.) The adage about leaders who lead by example is a true one. A team leader’s performance sets the tone for the team’s performance. A leader who doesn’t follow a team’s agreed-upon ground rules is unlikely to find that team loyal or accountable to them.

- Foster Team Relationships: A team leader must work to build two types of relationships: their personal relationships with each team member and relationships among team members. The first involves getting to know the members, including their skills and motivations, so the leader can create a more satisfying work environment and a more productive team overall. Building trust and transparency and cultivating open discussion between team leaders and team members are also critical. An open atmosphere can improve cooperation, team satisfaction, and the quality of a team’s work. This of course requires an ongoing effort.

For the second type of relationship, a team leader must be adept at spotting and dealing with conflict as well as addressing it proactively. You can do this by providing a platform for team members to voice opinions and share concerns. In most cases, mediating conflict is the best approach. A team leader should usually avoid dealing with conflict unilaterally. Encouraging honest communication is more likely to resolve conflicts amicably and improve interpersonal relationships than avoiding conflict or dealing with it in a way that leaves team members feeling they’ve been treated unfairly. Furthermore, providing this sort of platform for discussion is also likely to improve a team’s collaborative problem-solving abilities.

Team-building games, exercises, and activities are another way to get teams working together more effectively. Experts recommend different activities for every need, such as introducing icebreakers or bonding and increasing team appreciation. Check out these comprehensive resources for team-building activities and team-building games. - The Optimum Team Size: There’s a lot of research — and much more conjecture — about the optimum size for a team. The number you’ll hear touted most frequently, though, is five. This number derives from research that suggests a social rule for group sizes based on 5, 15, and 150. Popularized by social complexity expert Joseph Pelrine at the 2009 Software Practice Advancement Conference, this rule states that these three number limits constrain the number of social relationships of varying types an individual can maintain, with the number five originating from the natural limits of short-term memory

Other experts, however, criticize the practice of imposing team sizes from above without reference to the team’s context or purpose. Instead, they advocate letting teams determine optimum sizes from the bottom up via trial and error. This way, the actual environment in which a team works determines the team size, rather than pulling a number from a book.

The generally accepted wisdom is that larger teams see more social loafing, with teams larger than 20 devolving into subgroups that find it much harder to focus on a single purpose. Managers often prefer teams with odd numbers so that they can reach democratic decisions. Experts consider teams of eight prone to stalemates in decision making. In that particular case, the optimum size for a team can be anywhere from five to 19, as long as it’s not eight.

If the debate is too much to bear, take heart from experts who say the notion of an ideal team size is a fallacy. “Instead of organizing people according to some sort of a magic number, we should think of how to create an environment where people can easily adjust team size themselves depending on the context,” says trainer Pawel Brodzinski.

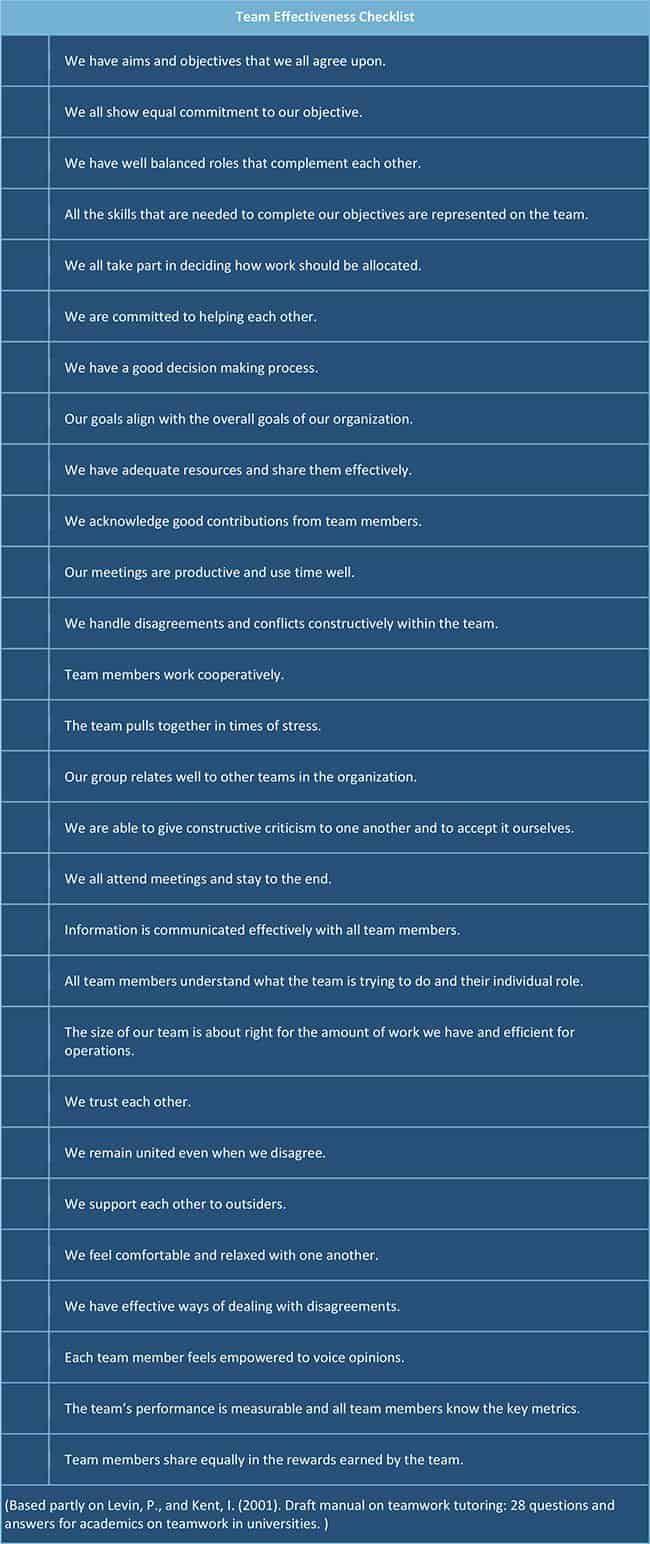

In 2001, academic teamwork experts Peter Levin and Ivan Kent, who at the time were at the London School of Economics, wrote a manual on teamwork in universities. They developed a checklist called "Are We a Team?” for assessing team effectiveness. That checklist remains popular today.

A helpful exercise for seeing how well your team is performing is to use a checklist or assessment tool like the one below.

Give a checklist to each team member For each statement below, answer to what extent do you agree? For each statement, mark on a scale of 1 (disagree strongly) to 10 (agree strongly).

When all team members have completed the exercise, collate point totals and ranges anonymously for individual questions and team effectiveness in total. Display these to the group and discuss areas of agreement or disagreement.

Download Team Effectiveness Checklist

In addition, Jack McGourty’s and Kenneth DeMeuse’s book The Team Developer is an electronic feedback and assessment system designed to promote team communication and improve performance via 360-degree team feedback.

The Stages of Team Development

Earlier, we talked about how a group of people aren’t necessarily a team unless they consciously organize themselves to pursue their goals. But how does a group of people become a team?

Leadership expert Jim Taggart says that groups of people who work together can consciously evolve into effective teams. He identifies five evolutionary stages in the transition from working groups to what he terms “high-performance teams.” These include the following:

- The Working Group: Members of a working group share information and interact to make decisions, but they do not share a common purpose or performance goals. As such, there’s no sense of accountability within the group. Everyone takes responsibility for their own results.

- The Pseudo Team: A pseudo team does not focus on collective performance, creating a common purpose, or setting common goals, though they stand to increase their impact by doing this. Many experts have weighed in on how to differentiate between real teams and pseudo teams.

- The Potential Team: Members of a potential team work to develop a clear common purpose and collective goals as well as agree to mutual accountability within the group.

- The Real Team: A real team has a common purpose and an agreed-upon set of collective goals. They organize themselves to achieve these goals and hold each other mutually accountable as they pursue the team’s goals.

- The High-Performance Team: Members of a high-performance team share the characteristics of a “real team,” and they also build successful relationships with each other and commit to each other’s growth and development.

In 1965, group dynamics scholar Bruce Tuckman developed a now frequently used model for group development. Amended in 1977, Tuckman’s model spans five stages: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning.

In the forming stage, the members of the group learn about each other and the functions they mean to execute. In the storming stage, they effectively thrash out the structure of the group, an effort that culminates in the norming stage. During this stage, they establish the rules and processes by which they will fulfill their functions. Performing involves the actual performance of work according to the processes agreed upon by the group members. Adjourning is the disbanding of the group, hopefully with members taking away lessons that will prove useful for future projects.

The Science of Team Roles: Building Teams That Work Together

Sports fans will often refer to an elusive quality called team chemistry, which is an assessment of a team’s composition and the relationships between its members. In theory, every team has an optimum chemistry in which the skills of its members mesh perfectly, and the working relationships between teammates are ideal. As such, a team’s chemistry is directly related to its performance.

Team chemistry in sports is impossible to measure objectively, but that doesn’t stop players, coaches, and fans alike from conjecturing about the ideal team composition. And the effort that goes into the pursuit of the ideal team combination, whether in sports or business, provides a wealth of knowledge. This knowledge comes from both a formal field of study called team theory and from less formal observations of how people play different roles within teams and how these roles impact a team’s performance.

In teamwork, we often use the word role to describe team participants as if they were characters in a play or personas. Roles encompass a number of facets related to how an individual fits into a team. It may describe the actions performed by an individual, the team function that they perform, and the way they conduct themselves as part of a social group. As such, a person’s role encompasses everything from their personality as a worker to the way they think to the formal functions they perform for the team.

Although the subject of team roles has been of interest since at least the 1940s, team theory as a field of study really began to attract attention in the 1980s, as noted by Eric Chong of Victoria University in New Zealand regarding the work of Dr. R. Meredith Belbin, a British management theorist. This work reflects the rise of personality inventory theories, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, based on the psychological types described by psychiatrist Carl Jung.

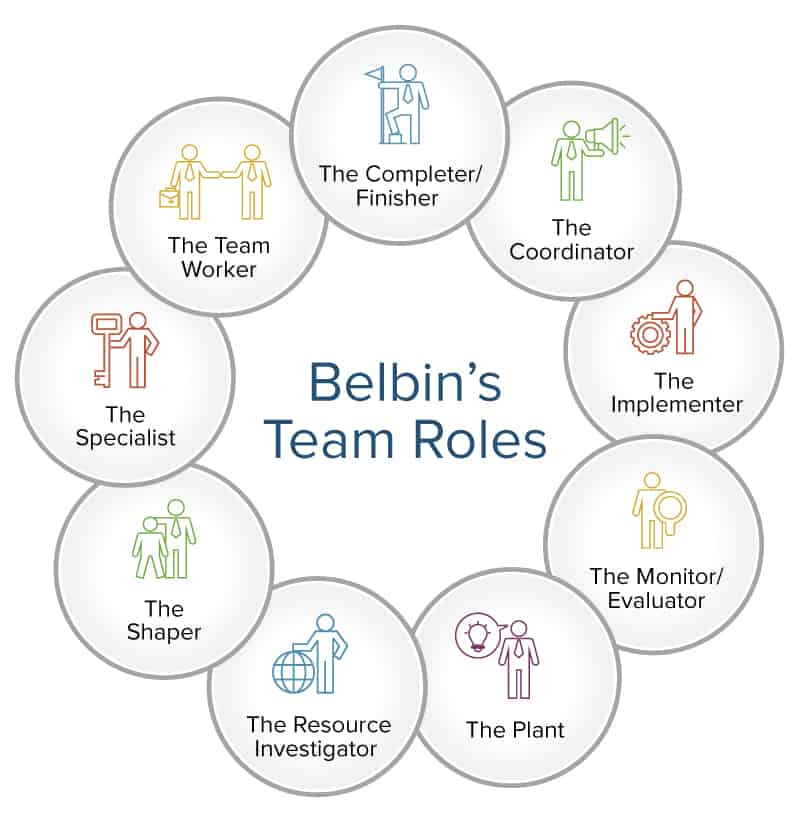

In 1981, Belbin outlined eight team roles that naturally emerge from people’s personalities. Team leaders must fill and balance these roles among team members to ensure high performance. Belbin’s work inspired substantial research into how team roles impact team performance. In 1993, he expanded his list to nine roles.

Managers charged with building teams refer to these roles and other systems of categorizing team roles in an effort to build more balanced and higher performing teams. Team members may also find the role-defining process an interesting way to understand their own and others’ roles. Belbin’s team roles include the following:

- The Completer-Finisher: The deadline-driven completer finisher is typically “anxious” about producing high-quality output and producing it on time. They’re diligent and conscientious, the type of person who carefully checks work for errors.

- The Coordinator: Mature and strong at organizing and delegating, the coordinator is a natural chairperson. They’re also good at facilitating decision making and setting goals.

- The Implementer: Implementers excel at taking ideas off the page and into the real world. Inherently practical thinkers, they’re disciplined and efficient workers.

- The Monitor-Evaluator: The monitor-evaluator is a natural skeptic who applies logic to discern the best course of action. They’re noted for reliable, well-informed judgment.

- The Plant: A creative, imaginative, out-of-the-box thinker, the plant is a natural problem solver.

- The Resource Investigator: The resource investigator is an extrovert, a natural people person who does well as the external “face” of the team. They excel at developing contacts and finding new opportunities by socializing.

- The Shaper: Always ready for a challenge, the shaper is the person the team turns to when deadlines are close or when things go wrong. Excelling under pressure, they can be exemplars for a team under stress.

- The Specialist: The specialist is an expert on a particular subject or skillset. They are knowledge bearers who work with single-minded dedication.

- The Team Worker: Natural diplomats, team workers excel at drawing teams together and minimizing harmful friction. They’re perceptive and prioritize the team’s interests over their own.

Alternative Role Systems for Building Teams

Alternatives to the Belbin roles are also popular. This is because some managers prefer to define roles by interpersonal needs, actual functions, or thinking styles (or any combination thereof), in addition to or instead of by personalities. The following are the most widely recognized alternatives to Belbin’s roles:

- FIRO (and FIRO-B): FIRO, or Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation, developed by American psychologist William Schutz in the late 1950s, is a theory of interpersonal relations. It predates the Belbin roles and focuses on relationship needs rather than work personalities. FIRO is based on the belief that individuals seek to fulfill three interpersonal needs when they are part of a group: affection/openness, control, and inclusion. Schutz created a measuring instrument, known today as FIRO-B (the B stands for behavior), that measures the extent to which each interpersonal need is expressed and wanted. In other words, it is the extent to which people initiated behaviors related to each of the three needs and to which they wanted or accepted behaviors related to each of the three needs from other members of their group.

Many organizations use modified versions of the FIRO-B measuring instrument to increase team effectiveness. For example, companies that administer the FIRO-B will encourage test takers to use their results to evaluate their roles within teams and question whether the needs-related behaviors they display as part of a team are a help or a hindrance to their teammates and to the team’s overall effectiveness. - Robert Heller’s Seven Roles: Robert Heller, a business journalist and the author of the 1999 book Essential Managers: Managing Teams, suggests seven team roles that resemble the Belbin roles but link to specific functions within teams rather than work personalities. Heller’s seven roles are leader, critic, implementer, diplomat, coordinator, innovator, and inspector.

Heller’s roles might appear similar to Belbin’s, but there’s an important difference in how the two systems view the nature of team roles. Belbin’s roles focus primarily on personalities and innate strengths that define the natural roles people play in teams, with the assumption that a consistently successful team will feature a balanced blend of personalities. Heller, however, views roles as inherently functional and related to the responsibilities an individual takes on rather than to aspects of their personalities.

- Peter Honey’s Five Roles: In his 1988 book Improve Your People Skills, occupational psychologist and management trainer Peter Honey effectively strikes a balance between Belbin’s personality-driven roles and Heller’s functional roles. From Belbin’s eight personality-driven roles, Honey distilled five functional roles: coordinators, challengers, thinkers, doers, and supporters. Honey’s system is useful for thinking about how individuals’ personalities align with a team’s specific functions.

- Kenneth Benne’s and Paul Sheats’ 26 Roles: Kenneth Benne and Paul Sheats were among the first to examine roles as part of group behavior theory. Outlined in their 1948 article, “Functional Roles of Group Members,” their role-categorization system is the oldest of those we’ve discussed here. Benne and Sheats defined 26 roles that individuals play within groups, sub-categorizing these as task roles, personal/social roles, and dysfunctional roles.

The Benne and Sheats system continues to be useful today because it tends to describe team roles as combinations of function and personality. Unlike the other systems of classifying roles, the Benne and Sheats system also identifies so-called dysfunctional roles, which hurt a team and decrease its effectiveness. These are worth describing in brief. - Aggressors: These members show an overt disrespect for teammates and have a tendency to make negative comments about others.

- Blockers: They criticize and turn down everyone else’s ideas without volunteering alternatives of their own.

- Recognition Seekers: These are show-offs who crave attention, engaging in irrelevant or even disruptive behaviors to keep themselves in the spotlight.

- Self-Confessors: This type indulges in the discomforting and distracting practice of using the group as a forum to discuss personal issues.

- Disruptors: Disruptors treat team activities as a break from real work, engaging in frivolities instead of contributing productively to what the group is doing.

- Dominators: These are autocrats who impose themselves on conversations at their teammates’ expense and tell teammates what they should be doing.

- Help-Seekers: They play the victim and try to elicit sympathy from teammates through self-deprecation.

- Special-Interest Pleaders: These people disguise their own arguments as those of third parties not represented within the team, typically resorting to stereotypes while doing so.

The University of Kent in England has added the following to the list of roles to avoid:

- Autocrats: They try to dominate or interrupt other team members.

- Show-Offs: Show-offs talk incessantly and seek to demonstrate they know everything.

- Butterflies: These folks change the topic frequently before the discussion is ready to move on.

- Avoiders: Avoiders bury their heads in the sand about tasks or group relationship problems.

- Critics: Critics find fault with all ideas but do not put forward alternatives.

- Clowns: These jokers do not invest in the real work of the group and engage in constant distractions and diversions.

Edward de Bono’s representation of different thinking styles as six differently colored hats is popular with management and team trainers at all levels because of its simplicity. In his 1999 book, Six Thinking Hats, de Bono identified six thinking styles: objective, opportunistic, careful/cautious, passionate, fertile, and abstract. Each of these thinking styles shapes the way individuals see the world, which is a function of personality. However, de Bono’s system stresses that individuals are not constrained by a particular thinking style, which is why he used changeable hats to illustrate the practice of examining a problem from different perspectives. He calls this parallel thinking — a more holistic approach to decision making that improves the effectiveness of the eventual decision.

De Bono’s six thinking hats are a useful tool for decision making in any context. For teams, the approach facilitates better decision making while also allowing members of a team to appreciate their teammates’ perspectives. The imagery of differently colored hats makes de Bono’s method especially useful for teaching the value of examining things from different points of view. Experts have also developed a number of hybrid and non-branded systems.

Examples of Teamworking in Specific Industries

Today, teamwork is an essential component of several fields. Let’s look at some of the ways managers apply teamwork in these fields.

- Healthcare: Teamwork in healthcare has been around since the beginning of the 20th century. A number of factors have driven the major period of growth in healthcare teamwork: increasing complexity; the growth of specialization; and population changes such as increased longevity and the rise of chronic diseases, which have forced healthcare providers to adopt more multidisciplinary approaches when treating patients who suffer from multiple health problems. Later research has found that teamwork in healthcare holds benefits for both health professionals and patients. Teamwork leads to a reduced number of errors and, therefore, improves quality while reducing pressure on individual healthcare providers. Teamwork is also at the heart of emerging models of healthcare like the Accountable Care Organizations in the United States.

Today, medical schools teach teamwork because it takes time to master, especially in a high-pressure environment. - Engineering: An inherently complex and often multifaceted field, engineering typically involves a substantial degree of teamwork, both with other engineers who specialize in the same or different areas and with the other technical staff who typically work with engineers. In the aftermath of the recession, American Society of Mechanical Engineers notes, engineering firms leaned their operations and refocused attention on the value of teamwork. The larger and more complex an engineering project is, the greater are the number and variety of people involved. In this scenario, the importance and potential impact of good teamwork increase.

Engineering education has a reputation for focusing on technical skills without emphasizing supporting skills such as interpersonal communications, teamwork, and people management. This practice continues even though engineers usually work on group projects as part of their formal education. Institutions including the University of Waterloo in Canada are re-evaluating and improving the ways in which they train future engineers in teamwork skills. - Education: Formal education is usually thought of as an inherently collaborative endeavor, and for students who dislike teamwork, it’s perhaps too collaborative.Surprisingly however, teachers suffer high levels of stress in large part because they see themselves as isolated. This may sound counter-intuitive. Aren’t teachers surrounded by students and colleagues for most of the working day? Educator and teamworking facilitator Sean Glaze says that too many teachers assume they have to tackle their challenges alone. This can quickly cause burnout, which helps us understand why attrition rates are so high among teachers. Teamworking is a solution for teachers, whether that’s team teaching with colleagues or collaborating in less formal ways.

- Aviation: Modern aviation depends on effective teamworking. Prime examples are air traffic control and the teams who handle ground operations, security, passengers, baggage, and more. The cabin crews on commercial airlines make a particularly interesting case because it’s not unusual for the members of a crew to have never met before the pre-flight crew briefing. Cabin crews fill diverse roles in a small space where coordination of movement is key, and they have to pull this off in a way that keeps commercial travelers safe and comfortable.

As Cabin Crew Head Patricia Green reveals, effective teamwork for a cabin crew centers on the speedy, effective designation of functional roles. Each member of the cabin crew must understand their function within the team and coordinate their movements with each other in the small cabin space. The designation of roles goes far beyond cabin service, of course. It includes knowing what to do in case of an emergency and dealing with the occasionally unpleasant customer. For paying customers, a cabin crew’s lapses in communication, coordination, and teamwork are, at best, unpleasant and, at worst, dangerous. - Software Development: If spontaneous teamwork shows the importance of understanding roles within a team, software development, with its typically quick turnaround times, shows the importance of prioritization when working on tight deadlines. Scrum is an iterative software development process that is part of the Agile school. It focuses on flexibility in order to meet customers’ frequently changing requirements without causing delays.

Scrum tackles these challenges by creating self-managing teams who can overcome organizational obstacles and silos. They coordinate their work with quick daily standing meetings and have other practices that reinforce teamwork such as retrospectives where team members offer feedback to one another and assess how they could improve the work process. Scrum teams also have well-established ways of prioritizing work over a limited period. This limited period is known as a sprint. - Military: Armed forces are among the oldest examples of teamwork, dating back thousands of years. Teamwork in the military isn’t a luxury. It’s a way to ensure survival, and it’s one of the fundamental principles of military action at almost any level.

At the heart of military teamwork is the idea that there’s strength in numbers. Having more people to look out for danger means that everyone is safer and that you accomplish more work in less time. Sharing life-threatening experiences builds a virtually unparalleled sense of loyalty and purpose in team members No wonder military veterans retain such close bonds years after they see action.

Despite the circumstances in which they’re tested, the principles of military teamwork are simple, which is why team trainers often allude to them in other, non-military settings. Above all else, military teamwork stresses commitment to a common cause — in this case, one worth putting life at risk. Second, military teamwork recognizes the contribution of the individual, which drives both specialization (allowing each member to contribute in the best way they can) and respect (meaning every member recognizes every other member’s contribution). Third, military teamwork drives home the importance of communication.

For other interesting examples of teamwork in action, check out #teamworking on Twitter. If you’re hoping to motivate and build spirit among members of your own team, see what people like Steve Jobs, J.C. Penney, and Henry Ford had to say about teamwork here and here.

Further Reading on Working as a Team

Here’s an extensive list of resources on teamwork that you may find useful:

Aggarwal, Ishani and Anita Williams Woolley. "Do You See What I See? The Effect of Members’ Cognitive Styles on Team Processes and Errors in Task Execution." Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 122.1. (2013): pp. 92-99.

Baker, David P., Day, Rachel, and Eduardo Salas. "Teamwork as an Essential Component of High‐Reliability Organizations." Health Services Research 41.4. (2006): pp. 1576-1598.

Bendersky, Corinne and Neha Parikh Shah. "The Downfall of Extraverts and Rise of Neurotics: The Dynamic Process of Status Allocation in Task Groups." Academy of Management Journal 56.2. (2013): pp. 387-406.

DeChurch, Leslie A. and Jessica R. Mesmer-Magnus. "The Cognitive Underpinnings of Effective Teamwork: a Meta-Analysis." Journal of Applied Psychology. (2010): P. 32.

Furnham, Adrian. "The Brainstorming Myth." Business Strategy Review 11.4. (2000): pp. 21-28.

Coutu, Diane. “Why Teams Don’t Work.” Harvard Business Review May. (2009).

Jones, Gareth R., and Jennifer M. George. "The Experience and Evolution of Trust: Implications for Cooperation and Teamwork." Academy of Management Review 23.3. (1998): pp. 531-546.

Klein, Cameron, et al. "Does Team Building Work?" Small Group Research. (2009).

Pentland, Alex. "The New Science of Building Great Teams." Harvard Business Review 90.4. (2012): pp. 60-69.

Salas, Eduardo, Dana E. Sims, and C. Shawn Burke. "Is There a ‘Big Five’ in Teamwork?" Small Group Research 36.5. (2005): pp. 555-599.

Siebdrat, Frank, Martin Hoegl, and Holger Ernst. "How to Manage Virtual Teams." MIT Sloan Management Review 50.4. (2009): P. 63.

Stevens, Michael J. and Michael A. Campion. "The Knowledge, Skill, and Ability Requirements for Teamwork: Implications for Human Resource Management." Journal of Management 20.2. (1994): pp. 503-530.

West, Michael A. "Effective Teamwork: Practical Lessons from Organizational Research." John Wiley & Sons. (2012).

Woolley, Anita Williams, et al. "Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups." Science 330.6004. (2010): pp. 686-688.

Wuchty, Stefan, Benjamin F. Jones, and Brian Uzzi. "The Increasing Dominance of Teams in Production of Knowledge." Science 316.5827. (2007): pp. 1036-1039.

Discover a Better Way to Foster Collaborative Teamwork with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.