What Is Social Compliance?

Social compliance is a continuing process in which organizations endeavor to protect the health, safety, and rights of their employees, the community and environment in which they operate, and the lives and communities of workers in their supply and distribution chains. Social compliance and social responsibility may address concerns about labor rights for workers, fair labor laws, harvesting and the use of conflict minerals, and general environmental and sustainability questions.

Social compliance may also be referred to as sustainability, which includes ethics (or the treatment of people and animals), the environment, and the economy. Social compliance auditing provides a way to document a company’s adherence to social compliance guidelines. Documenting practices and behavior provides a baseline for compliance monitoring. Socially responsible behavior and audit reporting can also inform socially responsible investing (SRI) choices.

Social compliance auditing is practiced mainly by retailers and manufacturers, also called purchasers or brands. Auditing allows brands to maintain oversight of the social practices of their supply chain, including maintaining company-established codes of conduct regarding purchasing and following local labor, health, and safety laws.

Auditing has grown in importance as global supply chains have increased and expanded to draw goods and resources from countries where labor laws do not exist or are inadequately enforced by local authorities. Assorted auditing methodologies and guidelines, often based on the United Nations International Labour Organization’s (ILO) principles and sometimes focused on specific industries, help brands understand what to audit.

Some guidelines stipulate that socially compliant companies focus more on people than on products or things. Ideally though, a happier workforce works harder and more efficiently and produces deliverables of higher quality. A content workforce and approving consumers should provide higher profits as well. Social compliance or sustainability includes three categories: ethics (the treatment of people and animals), the environment, and the economy.

Attention to social compliance also serves to protect your brand reputation among consumers. The information garnered during social compliance audits and by producing continuous improvement plans for suppliers and retailers can help companies address critics and articulate an understanding of worker conditions and necessary improvements.

What Does Social Compliance Mean in the Context of Social Psychology?

On a psychological level, social compliance works because we fear that not conforming to agreed-upon social rules will result in our ridicule or even exclusion from society. We feel the need to conform to receive praise and approval. In theory, within the context of corporate social responsibility, companies and brands who do good works for others receive rewards in the form of customer support and trade. Those who don’t comply lose business.

Ethics Vs. Corporate Social Responsibility

Although we sometimes use the terms social responsibility and social ethics interchangeably, they mean different things. Ethics, from the Greek word ethos, meaning moral character, is about conscience and morality in an individual’s or organization’s life. Ethics may provide the motivation to pursue corporate social responsibility, which concerns following law or policy.

The History of Social Responsibility

Although history tells of efforts throughout time to improve social well-being, the concept and practice of corporate social responsibility didn’t emerge until the middle of the 20th century. Some specialists believe that formal notions of corporate social responsibility have roots in the quality movement. In fact, two of W. Edwards Deming’s 14 Points for total quality management include the notions of ending “the practice of awarding business on price alone” and driving “out fear.”

Starr says that social compliance auditing dates back to the 1990s, when certain high-profile controversies over footwear and apparel sourcing occurred. Companies drew up supplier codes of conduct and spread them to suppliers during the first waves of what became known as corporate social responsibility. Auditing itself came into its own in the 2000s “and has continued to grow at a very fast pace.”

Starr talks about a colleague who was one of the first auditors to train with the U.S. Department of Labor to investigate apparel industry infractions: “He thought, this will go on for a couple of years, and we’ll clean things up because, surely, we only have to highlight this to people once, and people will start treating others better. Twenty years later, he now says that his grandchildren will still be working in the social compliance industry. And, as much as we continue to try, ultimately, the problem is not going away.”

Why Should You Care about Social Compliance Policy?

Evidence of abusive or illegal treatment within your company or supply chain can damage your company’s brand. Likewise, showing concern for sustainability down the supply chain can raise your corporate reputation and polish your brand.

In the best-case scenario, profits rise as consumers prefer to deal with socially responsible companies. Some brands that have begun with a sustainable outlook have done consistently well. Other legacy companies have assumed a social compliance mentality and even produced sustainable consumer products, which the public buys but which leaves investors less impressed.

Expecting consumer returns for sustainability can be a sticky wicket. “Social compliance has the challenge of people putting their money where their mouth is,” says Starr. She cites a study that involved offering two pairs of the same sock to people, one of which was labelled as sustainably made. Most people chose the non-sustainably made socks based on cost. In other studies, even those who declared their support for sustainable causes still chose the cheaper, non-sustainably made product.

What Is a Social Compliance Audit?

A social compliance audit, also called a social audit or an ethical audit, is a way to gain clarity into a business to verify that it is complying with socially responsible principles. Audits are usually conducted by an independent auditor. Auditors usually conduct these audits on external facilities, such as production houses, factories, and farms or packing houses.

However, some sources refer to a social audit as the internal audit or self-analysis undertaken by a company to understand how the organization itself affects the society in which it operates. When a company undertakes an internal audit, it may review its charitable giving, volunteering efforts, energy use, and green initiatives, such as recycling and composting, in addition to the more conventional considerations, such as its pay structure, benefits, and work culture.

Some companies share the results of its analysis with the public, whether the results are positive or not. Publishing a plan to become a more socially conscious corporate citizen can boost the public impression of a company.

What Is the Goal of a Social Compliance Audit?

A facility audit serves to verify and document that a facility is complying with prescribed standards of employee safety, health, freedom of movement, and correct pay along with local regulations and laws. As part of a long-term auditing program, audits verify that facilities are on a path to continuous improvement in working conditions. Audits may identify opportunities for improvement in the following areas:

- Underage labor

- Collective bargaining

- Discrimination

- Document review

- Dormitories

- Environment

- Freedom of association

- Harassment and abuse

- Health and safety

- Prison or forced labor

- Wages

- Excessive work hours

Starr identifies the ability to help people look beyond the audit event to the possible solutions as a major challenge in auditing: “A lot of people say, oh, it’s going to cost too much. And, my argument back to them is, how much does it cost to hire new employees? How much does it cost you for a quality issue if you have to rework the product or if people are returning the product. I’m not saying that happy employees are going to remove those problems, but, certainly, happy employees tend to work a bit harder, and you don’t have the quality issues because the workers are there trying to help you.”

The Auditor’s Role in a Social Compliance Audit

When conducting an audit, an auditor may be an employee of a purchasing company, or they may be on hire from a third-party firm. The latter option is often necessary to overcome language and cultural barriers.

The auditor collects data and evidence that they report to the facility and the client, i.e., the brand. Although the auditor can make suggestions, the auditor’s job is to be impartial. Rather than considering non-compliance as problems or issues, the auditor may consider these realities as opportunities.

Starr says the job includes the ability to “triangulate information.” She gives the example of a facility that says they work Monday to Friday with two shifts, information which is substantiated in employee interviews. However, it becomes obvious that deliveries happen on Saturday. If the workplace is closed on the weekend, who receives these deliveries?

Strong communication and people skills are essential. “The auditor needs to be a bit of an investigator,” says Starr. The knowledge required for the job is wide ranging, including anything from understanding payroll and working hours to knowing labor law. “They’ve got to talk to workers but also be able to talk to management, which can be two very different levels,” she explains. Auditors who display this flexibility and comprehensive knowledge of the workplace come from backgrounds as varied as human resources, accounting, legal, investigative journalism, as well as other auditing-related fields.

In addition, the work of an auditor can be arduous. Just the travel requirements alone can be taxing, necessitating quick turnarounds between sites in different cities or even different countries. After auditing during the day, auditors must then write reports at night, also often with a limited window for turnaround.

What Is the Association of Professional Social Compliance Auditors?

The Association of Professional Social Compliance Auditors (APSCA) was formed in 2015 and aims to establish professional competency guidelines and a code of conduct for social compliance auditors worldwide. Part of this effort seeks to limit the scope of audits that brands request to questions of working conditions and employee treatment rather than to structural engineering and environmental science.

How to Conduct a Social Compliance Audit

Audits may provide a way to gauge how well suppliers and retailers adhere to codes of conduct and local laws. But, before your business begins a social compliance initiative to review other organizations, you need to understand what you expect of them and what you expect of your own organization.

Conducting an Internal Audit

Self-auditing provides a way to understand where your company stands with regard to social compliance. Here are the steps for conducting an internal audit:

- Create a Statement of Social Responsibility: Start by reviewing your company’s code of conduct and code of ethics. Consider how you want to relate to employees, customers, and the society beyond your company and its business goals.

- Define Your Company: Is your company mainly about making products and profit while trying not to negatively impact society or the environment? Or, does your company consider sustainability goals to be its main purpose? If so, your company may be a social enterprise.

- Consider How Social Issues Affect the Company: Concerns might be immediate and close to home, such as graffiti or homeless people who shelter in your organization’s doorways at night. Social issues might also include how changing weather patterns or international conflict affect the harvesting of resources to produce the goods or services you sell.

- Set Social Goals: You may create a committee of employees and community activists to research issues and identify solutions.

- Consider Hiring an External Auditor: An external auditor trained and experienced in social compliance can bring a fresh perspective to situations and make suggestions for improvement. Take the auditor’s report and compare it to your company brand and social goals to see what work is required.

Auditing a Facility

Although the specific checklists and methodologies may vary slightly, audits usually follow the same pattern. As for internal audits, auditors familiar with social compliance issues bring discernment to viewing concerns and opportunities. Facility audits begin like this:

- The supplier registers with the brand all of the facilities that will be producing goods for the brand.

- The supplier agrees to be audited, including unannounced audits.

- The brand selects facilities for audit. The selection process may be based on a country’s, industry’s, or facility’s risk ranking. It may also be determined by the date of a facility’s last audit.

Why Do Facilities Fail Audits?

Although no facility is perfect and minor code and regulations violations are not uncommon, some infractions are too egregious to accept. Examples of critical and unacceptable offenses include using underage labor and forced labor, engaging in physical abuse, or permitting extreme safety violations. Moreover, obstructing an audit or attempting to bribe an auditor to secure a positive report will also result in audit failure.

Types of Social Compliance Audits

For external audits in particular, a variety of formats exists. Some brands pay for audits, but the logic behind making a facility pay for their audit is that, ideally, the facility in question takes ownership of the resulting report. Depending on your circumstances or your facilities’ countries of operation, your brand may choose any of the following courses of action regarding types of auditing:

- Staff your own internal audit teams and accept only their audits.

- Use third-party audit firms but accept audits only from a handful of approved audit firms.

- Choose the SMETA (Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit), which permits a range of audit firms to conduct the audit.

- Use the SMETA format but specify which firms you will accept.

- Allocate an audit firm to a facility, and give the facility a deadline for scheduling the audit with the contracted firm and for paying the fee. For allocated audits, the brand usually negotiates the rate so that all the facilities in a particular country pay the same amount.

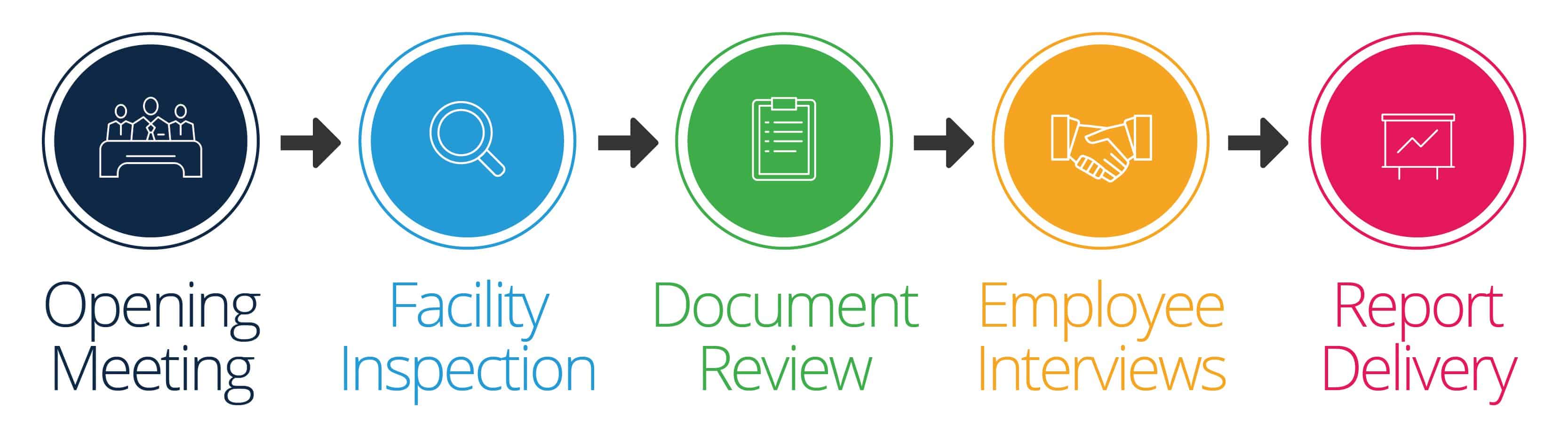

Audits may be announced, unannounced, or a mixture of the two, wherein the auditor notifies the facility that an audit will take place within a certain timeframe. The following steps outline the audit process:

- If the audit is unannounced, auditors explain the purpose of the visit to the facility managers. The auditors may specify a time for when the audit must begin, such as 30 minutes after their arrival and introduction. If the facility does not permit the audit to begin within that timeframe, the auditor leaves, and the event is considered an audit refusal.

- Review documentation, such as timesheets and payroll. Verify HR practices to confirm that the company is not employing underage workers. Review time, wage, and other records to see if the company adheres to local labor laws.

- Tour the facility to observe staff and management interactions and health and safety conditions.

- Conduct formal interviews with management and employees.

- Discuss any violations and corrective actions with management.

Walkthroughs Help Identify Common Violations

Walkthroughs reveal working conditions and should encompass the entire facility, including not just the production area, but also the washrooms, the cafeteria, the kitchen, the offices, and the dormitories, if applicable. Often, companies meet basic criteria.

For example, workers will probably have adequate room to move while working and hygienic toilet and cooking facilities. Common facility problems may appear primarily in the areas of production infrastructure and equipment or a lack thereof. These problems may include the following:

- Inadequate personal protection equipment (PPE)

- Gloves

- Hand, foot, and eye protection

- Hearing protection (ear muffs or earplugs)

- Respirators

- Hardhats

- Full body suits

- Inadequate safety guards on machinery. Examples of this type of negligence appear on the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) website and are included below:

- Don’t Prevent Contact: The safeguard must prevent hands, arms, and any other part of a worker's body from making contact with dangerous moving parts. A good safeguarding system eliminates the possibility of the operator or another worker placing parts of their bodies near hazardous moving parts.

- Aren’t Secure: Workers should not be able to easily remove or tamper with the safeguard because a safeguard that one can easily compromise is no safeguard at all. Guards and safety devices should be made of durable material that will withstand the conditions of normal use. They must be firmly secured to the machine.

- Don’t Protect Moving Parts from Falling Objects: The safeguard should ensure that no objects can fall into moving parts. A small tool that the system drops into a cycling machine could easily become a projectile that could strike and injure someone.

- Create New Hazards: A safeguard defeats its own purpose if it creates a hazard of its own, such as a shear point, a jagged edge, or an unfinished surface that can cause a laceration. The edges of guards, for instance, should be rolled or bolted in such a way that they eliminate sharp edges.

- Create New Interference: Any safeguard which impedes a worker from performing the job quickly and comfortably might soon be overridden or disregarded. Proper safeguarding can actually enhance efficiency since it can relieve the worker's apprehensions about injury.

- Don’t Allow Safe Lubrication: If possible, the user should be able to lubricate the machine without removing the safeguards. Locating oil reservoirs outside the guard using a line leading to the lubrication point will reduce the need for the operator or maintenance worker to enter the hazardous area.

- Exposed electrical wires

- Unmarked chemicals that the company does not store properly

Starr says that violations may not always appear in the production facility but may appear in accommodations for workers. She has seen workers housed in what appeared to be the structurally sound part of an unstable building until management realized the implications of doing so. Her worst case was a one-bedroom house that had no beds in sight but had 12 phone chargers and household electrical wire passing through the shower.

Documentation problems are common.

Payroll and attendance records may reveal subtle and not-so-subtle inequities in a company. The longer the range that an auditor can view, the better. These records can indicate if employees are receiving minimum wage and proper overtime wages and if they are working legal hours. If the company is keeping hand-written records rather than using electronic or punch-card methods, maximum hours can be difficult to determine.

While it may seem that enforcing limits on work weeks would be desirable to employees, this is not always the case. In some circumstances, employees value long work hours and want more hours to earn more pay.

Documentation on hiring practices and conditions of employment reveal discriminatory practices, disciplinary measures, what violations result in termination, how one should perform termination, and whether companies retain employee ID as a condition of employment.

Auditors can unearth common problems during the employee interview process. After gaining an understanding of the company through a facility walkthrough and a review of documentation, auditors conduct random interviews with employees. Interviews may reveal complaints and a lack of understanding about employee rights regarding working hours, wages, or safety options.

There are several key terms regarding audit results. Auditors categorize violations as non-critical, critical, or severe. They categorize audits as acceptable, needs improvement, at risk, or non-compliant. There are basically two categories of non-compliant results:

- Probationary Non-Compliant Results: The auditor may give the facility the opportunity to correct problems within a specified number of visits. If the facility does not correct the violations, the auditor deactivates it from the supplier list.

- Grounds for Failure and Zero-Tolerance Violations: Auditors determine intolerable violations after a thorough review of documentation and financial docs and through interviews. Auditors may ban suppliers from working with a brand for a specific number of years. Grounds for audit failure and zero-tolerance violations may include the following:

- Underage labor

- Corporal punishment

- Forced labor

- Conflict of interest, often in the form of offering some type of bribe to auditors to influence the outcome of the audit

Corrective Action Plans for Social Compliance Violations

Regular communication between the auditors and the facility ensures that the company understands the issue and can help determine the root cause of violations. But, that doesn’t mean the solutions are easy. “It’s more difficult to truly fix the underlying causes of social compliance issues,” says Starr. She continues, “For example, when people have animal health and welfare issues, if you look at the root cause of why someone has mistreated an animal, I’d be willing to bet that this person is being mistreated by the facility, a fact which the mistreated employee is then taking out on the animal.”

Sometimes, it’s a question of changing cultural patterns. For example, factory managers may think that yelling at employees is okay because the culture itself is expressive and loud. “But, that is still potentially abusive behavior, and it amounts to not treating people correctly,” explains Starr. In other cases, the issue to be modified is all too human. “A lot of people don’t want to admit that they’re not treating their workers well,” explains Starr. She adds, “They feel that people should be able to stand up for themselves and speak up. But, that just doesn’t happen. They seem to feel that it’s their right to treat other people the way they want.”

Positive Social Compliance Auditing Stories

For all the problems that inaugurated social compliance audits 20 years ago, auditing can bring forth positive outcomes, often when facility management has unintentionally violated guidelines. “You can see the excitement in management when you talk about issues and also see happy workers when good plants make improvements.” Starr says. “There are a lot of really good social audit stories out there. There are a lot of really good people out there,” she emphasizes.

What Is a Business Social Compliance Initiative Certification?

The Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI) is not a certification but provides an improvement methodology for factories and farms that aim to be certified. BSCI is an initiative of the Foreign Trade Association (FTA), and works to provide a consolidated compliance framework that can be applied to multiple industries.

SA8000 Certification

Governing workplace quality, the SA8000 certification standard was published in 1997 by Social Accountability International, a non-profit social welfare group. A voluntary program, SA8000 is considered the first global standard, scalable to any size of organization in any country.

An SA8000 certification indicates that a company has maintained SA8000 standards for three years. It encourages self-management in social accountability areas but provides for third- party audits to ensure that companies are compliant. Based on the provisions of the International Labour Organization and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the standard centers on eight measurable areas, plus management:

- Child labor

- Forced labor

- Health and safety

- Freedom of association and collective bargaining

- Discrimination

- Disciplinary practices

- Working hours

- Remuneration

- Management system

What Is a Sedex Audit?

The Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit was developed by the Ethical Trade Initiative (ETI) to package best practices in existing audit methods. With SMETA, a supplier can share one audit with multiple brands, thus, saving effort and money. It is based on ETI principles and local law and focuses on health, safety, and labor law and optionally on business ethics and the environment.

Social Compliance Checklist

Although slight differences may arise with audits, the requirements are generally the same. This checklist, developed from the BSCI audit format, indicates the many types of documentation, equipment, and infrastructure an auditor might look for. Another version of a checklist is specific to the furniture industry.

Issues That Arise Within the Social Audit System

Despite the many frameworks and organizations created to manage social compliance auditing and the rise in companies who require it from suppliers, the system is not perfect. Problems with the auditing system do exist. Some companies choose the lowest-bidding supplier even if the bidder’s social compliance is poor. As a result, it’s possible that suppliers who try to do the right thing sustain higher costs.

In some instances, work can be dangerous for auditors. They may be offered bribes and may be threatened to remove negative findings from reports. Occasionally, they are beaten up. They may be held against their will, needing the police to free them or needing tact and negotiation skills to extricate themselves. If auditors report harassment back to the brand, the brand may choose another audit firm, seeking no consequences for the supplier or facility.

On the other side, unscrupulous auditors may pressure a factory to pay a bribe in order to get them to overlook infractions or give a good report. “Consultants” may pressure a factory to hire their consulting services to pass an audit.

Social Compliance Resources: Initiatives, Methodologies, and Organizations

Social compliance efforts are organized through trade associations that study social compliance problems and corrective actions and that work to improve methodologies used in social compliance auditing.

The Global Social Compliance Programme (GSCP), an initiative of the Consumer Goods Forum, was founded by private goods manufacturers and retailers to coordinate and find common elements among worldwide social compliance initiatives. The following are some of the groups and initiatives focused on sustainable supply chains:

- Fair Labor Association (FLA): The FLA is a collaboration of companies, universities, and other groups that help ensure safe working conditions.

- Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production (WRAP): WRAP is a Virginia-based nonprofit. They are focused on providing guidance to clothing and footwear manufacturers worldwide regarding the ethical employee practices based on the International Labour Organization’s decisions. WRAP published 12 Principles.

- AIM-PROGRESS (Association des Industries de Marque or European Brands Association): A global voluntary initiative of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) producers who promote “responsible sourcing,” they are supported by AIM in Europe and the Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA) in the U.S.

- Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI): The initiative is a supply chain management framework to help companies implement socially responsible policy in factories and farms by offering a single, ready-made code of conduct and implementation system for use by brands. BSCI provides neither auditing nor certification.

- Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI): A collaboration of companies, trade unions, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the ETI promotes global worker rights.

- International Council of Toy Industries (ICTI): ICTI focuses on toy safety, ethical marketing to children, and the social responsibility of toy manufacturers.

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA) (formerly the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition [EICC]): The RBA structures discussion and initiatives around social, environmental, and ethical issues in the electronics supply chain.

- Social Accountability International (SAI): Founded by American investment banker Alice Tepper Marlin to support equitable treatment of workers, SAI developed the SA8000 audit format.

- Sedex: A non-profit group of suppliers with the world’s largest platform for sharing data on ethical sourcing, the tracking of human rights, sustainable sourcing, and other social responsibility concerns, they publish the Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit, one of the most commonly used CSR audit formats in the world.

- ISO 26000, Social Responsibility: Published in 2010 by the International Organization of Standards (ISO), this document offers no certification, only a guideline for organizations considering their social responsibility. It recognizes seven basic principles of social responsibility: accountability, transparency, ethical behavior, respect for stakeholder interests, respect for the rule of law, respect for international norms of behavior, and respect for human rights.

What to Look for in Social Compliance Software

Some brand organizations have custom software that can track suppliers, vendors, facilities, and reports and provide alerts indicating when audits are required. If custom solutions are not an option, an off-the-shelf tracking package may suit you. Tracking complex, global supply chains that must comply with a myriad of local laws and regulations is not something you can do in a spreadsheet. Social compliance software should be able to perform the following functions:

- Draft and store codes of conduct

- Store training programs and supplier onboarding packets

- Automate audit reminders and record audit reports and interactions between auditor and supplier

- Track compliance-monitoring efforts

- Track subcontractors

- Record issues and track corrective actions

- Generate reports and email

Improve Social Compliance with Work Management in Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Any articles, templates, or information provided by Smartsheet on the website are for reference only. While we strive to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability with respect to the website or the information, articles, templates, or related graphics contained on the website. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

These templates are provided as samples only. These templates are in no way meant as legal or compliance advice. Users of these templates must determine what information is necessary and needed to accomplish their objectives.