What Is Project Design?

Project design is one of the earliest stages in the project lifecycle. During project design, create an outline that includes a project description, a schedule, goals, outcomes, and objectives, major deliverables, and a budget estimate.

It’s important to involve your team and other key stakeholders in project design. This will help ensure important details are included, and that your project is realistic and achievable. Your project design should be carefully documented, and a variety of visual aids may be incorporated, as well.

Project Management Guide

Your one-stop shop for everything project management

Ready to get more out of your project management efforts? Visit our comprehensive project management guide for tips, best practices, and free resources to manage your work more effectively.

6 Steps to Effective Project Design

The project design phase includes six steps. First, define your goals and determine your outcomes. Next, identify potential risks and prepare your materials. Finally, outline your budget and determine your approval and monitoring processes.

1. Define Project Goal

First and foremost, you should meet with your team and key stakeholders to define the ultimate goal or outcome of your project. This might be the product that is going to be developed, the service that will be provided, or the problem your project will solve.

Consider the needs and expectations of all stakeholders and/or beneficiaries when determining your goals, and get their approval early on. Make sure your team members weigh in on the accuracy and feasibility of the goals you define, as well. Remember, the more of this you can figure out ahead of time, the easier your project will be to manage later.

2. Determine Outcomes, Objectives, and/or Deliverables

After the primary goals have been established, break each down into smaller, more manageable pieces. In some industries, such as nonprofit and education, these pieces are objectives or outcomes—for example, solutions to problems that have been identified for the population you’re trying to help, or learning goals that students need to achieve. In other industries, such as project management and software development, the smaller pieces may be deliverables, such as a marketing plan, or a prototype of the software.

During the design phase, some organizations break down outcomes, objectives, and/or deliverables even further into the tasks and activities required to complete them. Others save the task/activity breakdown for a later phase of the project life cycle, such as during project scheduling. It’s up to your organization to decide what works best.

Whatever your process, it’s helpful to use the SMART acronym when identifying outcomes, objectives, and/or deliverables. Make sure they are:

- Specific: Be as clear and direct as possible so that later, you can plan the tasks that will be performed to achieve them. Provide specific guidance on which resources are involved and their roles.

- Measurable: Outcomes, objectives, and/or deliverables must be quantifiable. This way, you’ll be able to measure results and track progress.

- Achievable: Make sure goals can realistically be achieved given the resources, budget, and time frame available.

- Relevant: All outcomes, objectives, and/or deliverables should logically result in achieving project goals and producing intended results.

- Time-Bound: Provide a timeline for when they will be achieved/completed.

“Outlining projects [and] building that structure first is the key,” says Heather Cazad, Director of Operations at education-focused nonprofit Character.org. “You can get caught up in the minutiae of large projects, but you have to work from the outside in toward the details. Break up large sub-projects into smaller pieces.”

3. Identify Risks, Constraints, and Assumptions

Now that you’ve determined what you want your project to achieve, identify anything that could stand in the way of its success. Document any risks and constraints on budget, time, or resources that could affect your team’s ability to reach goals, milestones, and outcomes. Then try to resolve as many of these problems as you can. This will help prevent delays once the project is underway.

It’s also good practice to document any assumptions made during the project design phase. These will come in handy when you create a Statement of Work (SOW) and/or project schedule, and will also help you estimate costs more accurately.

“Look out for assumptions,” says Lonergan. “All projects are built on assumptions, and smart project managers know this. At the start of the project, the scope for assumptions is unlimited. Smart project managers capture these within the design process, then deal with them in a very disciplined manner.”

For example, if you assume that a necessary piece of equipment will be available when the project reaches the installation phase, this should be noted. That way, if the person who makes the schedule discovers the equipment isn’t available until a later date, you’ll be informed and can adjust the timeline and budget accordingly—before the actual work begins.

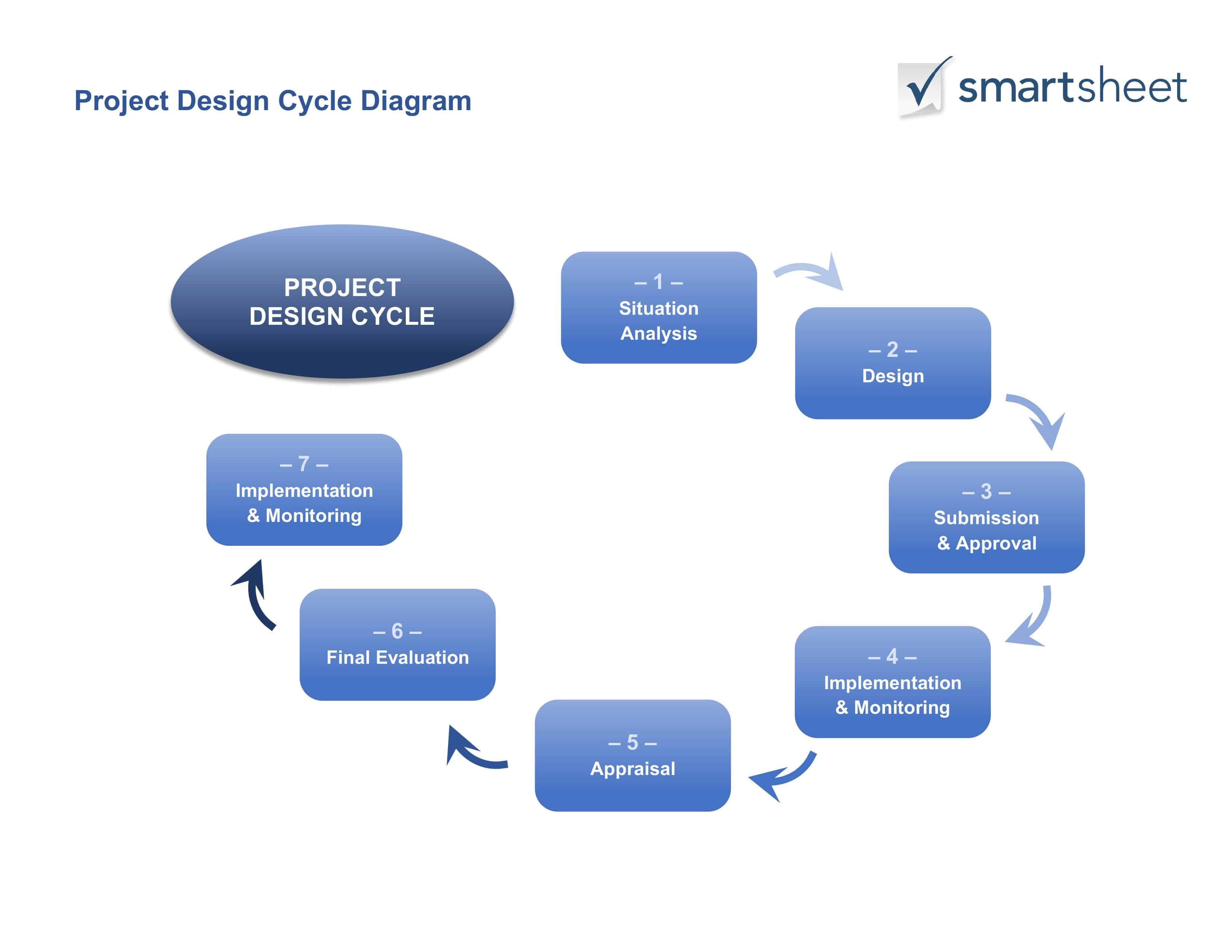

4. Prepare a Visual Aid

Once you’ve determined your goals, outcomes, and risks, you can prepare a visual aid to represent part or all of the project. Visualizations are particularly common in the creative, construction, nonprofit, and software development verticals. However, using visualizations can be useful when managing any type of project since they provide team members and stakeholders an easily understandable snapshot of the project’s goals, outcomes, deliverables, products, services, and/or functionality.

Visual aids may include:

- Sketches or drawings

- Plans, schematics, or rough blueprints

- Flow charts

- Site trees

- Gantt charts

- Screenshots or screen designs

- Photos

- Prototypes

- Mind maps

- Whiteboard drawings

The type of visual aid you choose may depend on your industry. In project management, Gantt charts, mind maps, and whiteboard drawings are often used to visualize early-stage project designs. In software development, diagrams, trees, charts, or maps of the software architecture and/or functionality are common (more on this in the software development section below). Prototypes or models may be created for product development projects. While flow charts are common in the nonprofit realm.

Download Project Design Cycle Diagram Template

In construction project management, blueprints, drawings, schematics, and/or plans are produced, which are then reviewed by an engineer or architect. Once approved, working drawings are created out of the preliminary plans, which are used when performing the actual construction.

5. Ballpark Your Budget

It’s important to know the budget right from the start. Even if you don’t have a complete picture of the costs and incomes your project will generate, create a budget in as much detail as you can. The clearer you can be about your budget during the project design phase, the less likely you are to experience unexpected cost overruns later.

Estimating your budget will also help you determine the feasibility of the project. If the cost is more than your client, customer, funding source, or partnering entity can spare, the project can’t realistically be undertaken.

6. Determine Approval and Monitoring Processes

Now that you have a picture of the project’s goals, risks, and budget, decide how success will be determined. List the criteria you’ll use to judge whether deliverables, outcomes, and the final product have been achieved. You should also determine what processes must be followed in order for the project and its elements to be approved, and who is responsible for approval.

“The goal of the design phase is to have a definite understanding of what success looks like to the project sponsors and key stakeholders,” says Dave Wakeman, Principal at Wakeman Consulting Group. “What I want isn't important. What the sponsors and stakeholders want is. So I spend a tremendous amount of time understanding what success means to them.”

For projects that are quite technical or complex, you may also want to add a stage for “proof of concept.” This allows the preliminary design of a product or service to be tested for viability before the project advances to the next phase. Performing this stage can save a lot of time and money if the test isn’t successful. If your proof of concept is feasible, this can reassure clients, stakeholders, and/or funding sources they have made a good investment.

Of course, you must also use the proper documentation to capture all this information. In project management, the output of the design phase may be as simple as a Gantt chart, a flow chart, a work chart, or a hierarchy chart that you carry into the project planning phase.

However, many projects do not have a formal design phase. In this case, there is an initiation phase, during which you create a detailed project plan, project charter, or project initiation document (PID). The approach you take will depend on your organization.

“Sometimes our marketing plans or branding initiatives have several audiences, so confirming who we're targeting for each particular project helps focus the team and clarifies objectives,” says Laura Puente, Director of Marketing Communications for Brand Experience firm BrandExtract.

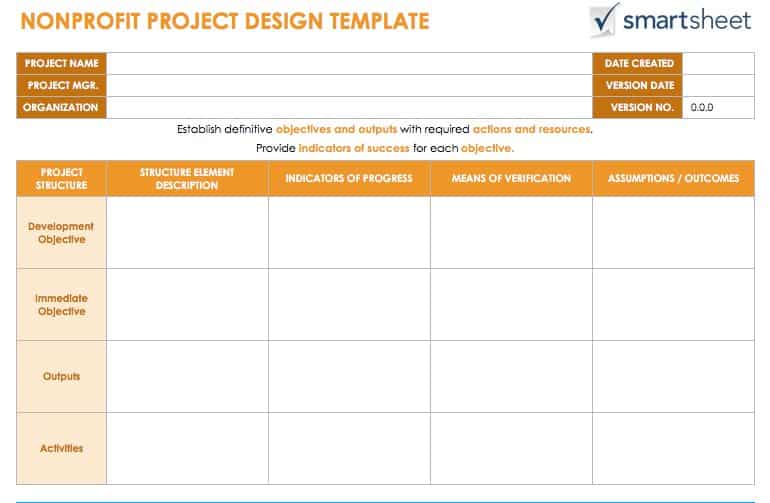

Project Design for the Nonprofit Industry

Project design for nonprofits will differ based on the target population and the regulations of your operating area. That said, nonprofit project designs typically involve creating monitoring and evaluation plans and assessing your stakeholder's capabilities.

Nonprofit project design centers on problems and solutions: it involves identifying issues that impact a target population, instead of finding opportunities for your organization to lessen or eliminate them. Based on information from United Nations agency the International Labour Organization, renowned nonprofit the International Youth Foundation, and other industry experts and resources, here is the basic approach to nonprofit project design:

1. Analyze the situation and identify problems. Conduct a “situation analysis” or “needs assessment,” which involves clearly identifying your target group so you can gain a deep understanding of their needs. Your target population includes direct recipients—those who will benefit from the immediate outcomes of your project—as well as the ultimate beneficiaries, or those who will be impacted by your project in the long term.

Analyze all available data to get a clearer picture of your target population. Look at demographics, social and cultural factors, politics, the local infrastructure, economic conditions, and any other issues unique to the area or population. You can find this information in existing reports and research, and from direct observation, interviews, and/or focus groups with members of your target group.

Next, identify the major problems affecting this group, as well as the causes and negative effects of those problems. Look for any notable strengths and weaknesses in the target population, as well as in your own organization. This exercise will help you identify which problems your organization could have the greatest impact on, and prove the need for your project to donors and stakeholders.

For example, maybe one of the problems is that your target population experiences a higher prevalence of certain communicable diseases. One cause of the problem might be poor education about disease prevention. The effects could include higher mortality and unemployment rates. If your organization excels at educating people about proper health care, you have an opportunity to reduce the impact of this problem.

2. Assess your stakeholders’ capabilities. Your next step is to identify and analyze other current and potential stakeholders, which may include your organization’s funding sources, local and regional government agencies or entities, and other nonprofit groups working in the area. Entities or organizations that can help you better reach your target population are known as “entry points,” and should be identified as such in your project design documentation.

Conducting a stakeholder analysis shows you which groups might have an interest in your project and its outcomes. It will also reveal:

- Which groups could help or hinder your project

- What resources they have

- Their level of influence or authority over the population and the project

- How high a priority your project is to them

This will allow you to choose the right organizations to partner with, and identify risks posed by those who could restrict your work.

3. Identify the long-term and short-term outcomes you want to achieve. Now that you know the problems, identify the solutions your project will provide. As with any project, you should first identify the ultimate goal or outcome of your project and then break it into smaller outcomes and objectives that will help you reach that goal.

Nonprofit projects must establish both long-term, strategic outcomes (also known as “development objectives”), as well as nearer-term objectives. Some organizations only identify “immediate objectives,” while others also include “intermediate objectives” that serve as a bridge between the longest- and shortest-term goals.

When identifying your outcomes, use SMART criteria. Then, phrase them as positive statements that demonstrate how your organization will decrease or eliminate the impact of the problem for your target population. For example: “Implement a program to educate 1,000 people in a rural town in Uganda about how to protect themselves from communicable diseases by the end of the project.”

4. Create an implementation or work plan. Here, you’ll outline the activities that need to be performed in order to achieve outcomes. Identify the long- and near-term objectives the activities will impact, as well as any outputs they will produce. The activities should also meet SMART criteria. It’s a good idea to put these activities in a timetable, as this will make scheduling easier.

Next, list the inputs (staff, financial, and equipment resources) required to carry out the tasks, as well as the costs, or output, the activities will accrue. Using this information, you can create a preliminary budget. Be sure to work with your organization’s financial specialist to ensure your budget estimates are accurate.

5. Make a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) plan. Nonprofits are accountable to stakeholders and donors and therefore must closely monitor and evaluate the results of their work. “Monitoring” refers to tracking whether activities are being properly executed on a regular basis. “Evaluation” means quantifying the impact of the activities and inputs on the project’s outcomes and outputs. Evaluations are done less frequently—usually at the end of key phases or milestones.

The M&E plan outlines how your organization will collect, enter, edit, analyze, and interpret project data. To create a plan, choose “indicators” (characteristics that will show whether the desired results have been achieved) and “targets” (the amount of progress you expect to make toward completing an objective in a certain amount of time). These should be specific and quantifiable, and may align with project milestones.

In your plan, identify the tools and methods that will be used for data collection and analysis; who is responsible for M&E; where it will be performed; the M&E budget; and how reporting will be handled. Also define the process for potential follow-up actions.

Once your nonprofit project design is complete, you can use it as the framework for a formal proposal, which will help your organization secure funding in a later stage. For further guidance, download our nonprofit project design template.

Project Design for the Education Industry

Project design in education is increasingly focused on outcomes. There are several methods that you can use to design education projects, such as giving students “voice and choice” or having them present to a real audience. All of these methods are results-oriented.

While nonprofit project design centers on problems and solutions, education project design focuses on questions and answers. In project-based learning, teachers help students learn necessary knowledge and skills by designing projects that engage them in independent research and inquiry, resulting in the presentation of a final learning product.

While every project will vary, the following steps are generally recommended in any type of education project design. These steps are based on information from the Buck Institute for Education (BIE)—a renowned nonprofit that helps educators teach project-based learning—as well as on testimony from industry experts.

1. Identify the learning outcomes. The projects you design should impart students with important knowledge and skills that help them achieve learning outcomes. These outcomes should be based on learning standards, and must cover key subjects for the class and grade level. The project should also facilitate teaching and assessment of the skills students need most to succeed in the modern world (i.e., problem-solving, collaboration, communication, and the use of technology). Identify the primary skills and outcomes that your project will help students achieve.

For example, a learning outcome might be: “Students will be able to articulate which social, political, and economic factors contributed to the onset of the Vietnam War.”

The Institute for Meaningful Instruction creates curricula and instructional material for teachers using nonlinear instructional design (NLID), which is a framework within which project-based learning can take place. With NLID, instructors and project designers first determine the learning outcomes and content they want to teach. Then they work backwards to determine the course material, evaluations, and performance criteria that will be used.

Ryan O'Donnell, a Co-Founder of the Institute for Meaningful Instruction, explains the approach of designing education projects in the reverse order of how students will experience them allows “for the best outcomes for each individual student or organization.

Tim Hudson is Vice President of lLearning at DreamBox Learning, which designs digital math lessons, software, and other resources for teachers and students. His organization takes a similar, outcomes-based approach to project design, which he describes as a backward design process.

Prior to joining DreamBox, Hudson successfully designed education projects in public schools using this outcomes-based approach.

“In particular, I helped facilitate the long-range strategic planning process for the Parkway School District in suburban St. Louis,” he explains. “Over the course of multiple years, our Steering Committee developed a new mission and vision for the district that defined the essential outcomes for all students. … This project was successful because we engaged the community, planned backwards, and explicitly drew the distinction between the means and ends.”

2. Choose the driving question that the project will answer. Upon completing the project, students should arrive at the answer to a “driving question” that helps them achieve the intended learning outcomes. In order to encourage critical thinking, the question should be reasonably challenging for students in their respective grade levels to answer. It should also be open-ended, with more than one “right” answer, so students have the freedom to inquire and explore.

Driving questions serve as the project’s thesis, and help students understand why they are doing the work. They should be phrased in clear, specific language so they are easy to understand. Perhaps most importantly, driving questions should inspire passion and excitement about answering them.

Examples of driving questions might be: Why are civil rights important? or Was the Iraq War justified?

3. Structure the project to enable a process of continued inquiry. Not only should your project help students answer a driving question that you supply, it should also provoke them to ask and answer questions of their own. Remember, all project design involves breaking larger components of work into smaller ones that contribute to achieving the ultimate goal. Therefore, students should use the driving question to brainstorm smaller questions that help them arrive at the ultimate answer.

You may start this brainstorm with the whole class, but the goal is for students to engage in the inquiry process on their own—in other words, answering one question should prompt students to ask themselves another. This pattern of discovery and exploration continues throughout the life of the project, until the driving question is answered. It can also be helpful to focus on real-world questions that affect students’ lives; this will better engage the class and drive learning goals home.

4. Give students “voice and choice.” As the BIE describes, education project design should allow students to have a “voice and choice.” That means students get a say in the questions they ask and answer, the resources they use, how they manage their time, their process for completing and organizing tasks, who is on their team, and other important elements. This helps the project feel more meaningful to individual students.

What’s more, the tools, resources, tasks, and evaluation standards you use should mimic real-world conditions as closely as possible. Instead of simply giving students a textbook to look up the answers in, they should be encouraged to drive their own research and find their own answers through sources they choose. These sources could include anything from watching a documentary film to talking with members of the local community.

5. Include time and guidelines for reflection, feedback, and revision. Both during and after the project, incorporate opportunities for students and teachers to reflect on the learning, give and receive feedback, and make necessary revisions. Include guidelines in your project design document for when, how, and with whom reflection and feedback sessions should occur. Sessions should be well-structured, and should occur at key points throughout the project life cycle. The goal is to help students understand what they’re doing right, what needs improvement, and how the project relates to greater learning outcomes.

Your project design document should describe what guidelines and methods will be used to provide feedback and reflection. For example, you may want to include things like whether sessions will involve individuals or the whole class; what tools students should use to record reflections and feedback (such as a log, journal, or software program); and what format should be used for these sessions (such as a discussion, focus group, or survey).

6. Have students present their work to a real audience. The result of a successful education project design is a learning product that students present to the public. This could be a report, presentation, service, performance, or anything else that allows students to explain what they learned, how they conducted their work, and why they made certain choices. By presenting their product to an audience outside the classroom, the project becomes more authentic to students and gives them valuable experience for the real world.

Your project design documentation should explain how the learning products will be made public, who they will be presented to, what impact this will have on the audience, and whether work will continue after the product is presented. List any resources (such as personnel, equipment, or facilities) students will need. Include what the product’s content will be, and which learning outcomes and skills will be evaluated.

To get started on your project design document, download our education project design template.

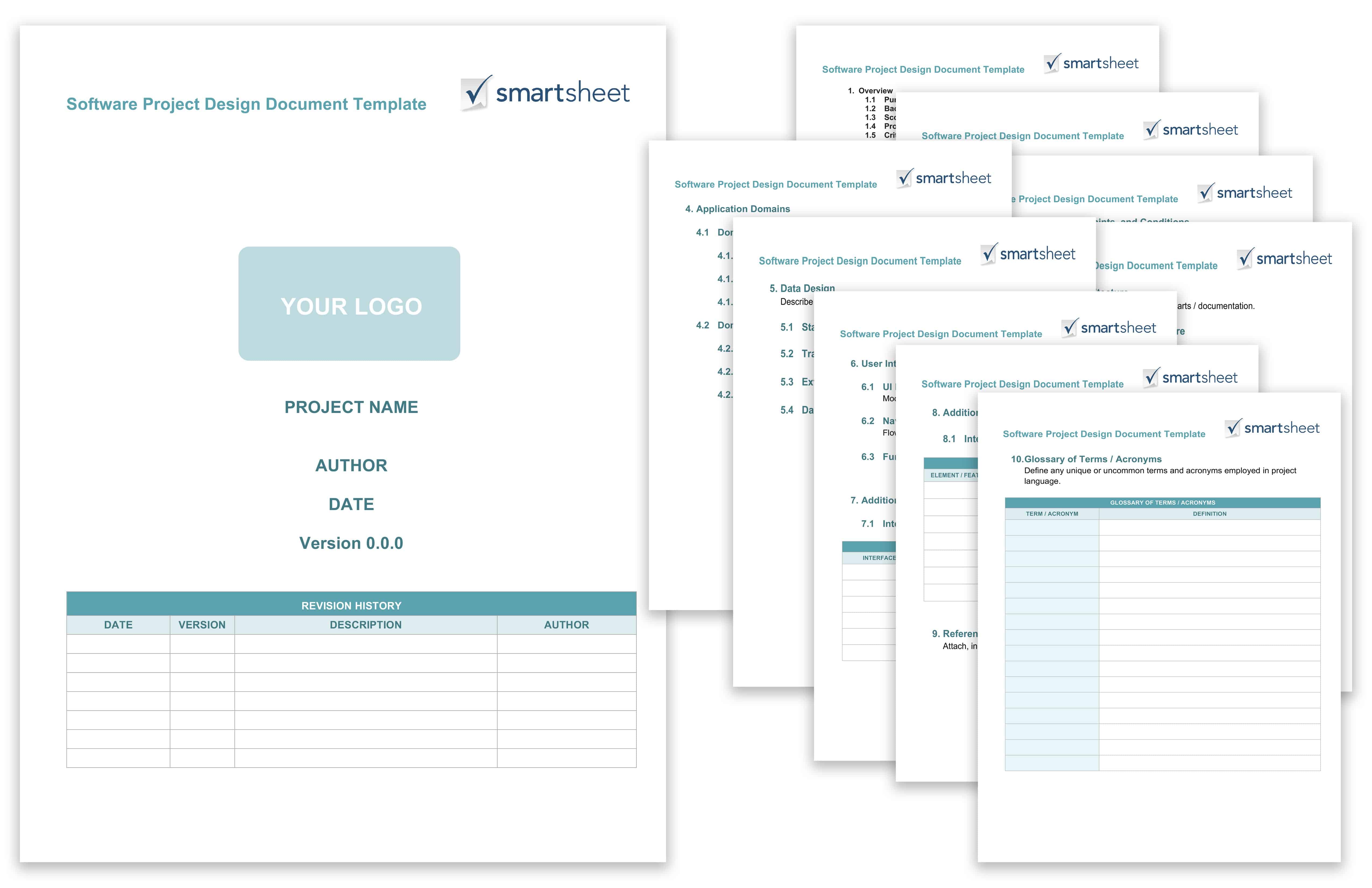

Project Design for the Software Development Industry

Software development projects can be highly technical and complex. These project designs have a broad range: from simple diagrams or descriptions of requirements and functions to long, detailed documents outlining every technical specification of the application or system.

However, most software development project designs have a few common elements. These are recorded in what is commonly referred to as a Project Design Document (PDD); this may also be known as a “software design document” or “software design description.”

Leigh Epsy, Project Manager and Contributor to ProjectBliss.net, says that in her software projects, “the primary goal is to ensure that the team knows how the solution will be built. This involves not only hardware, but data flow and other considerations. … design architecture, security, and long-range planning all need to be factored in.”

Espy adds that you should “rely on your team's expertise for design” and consult “architects and tool product owners,” rather than trying to create the whole PDD yourself.

Jeff Kear, CEO of event registration software vendor Planning Pod, follows a familiar process when designing his software development projects. He starts by identifying one primary outcome (for example, enabling software users to send email invitations), and then breaks that outcome down into smaller deliverables, such as a feature that allows users to add attachments to email invitations.

“Once I have my goal structure in place, I can then talk with my developers to determine the sequence of goals/deliverables, and how much time each should reasonably take,” says Kear. “From there, I can start to break down sub-goals for each deliverable, and start setting deadlines for initial concepts/sketches, wireframes, etc.”

In addition to following the general steps for project design listed above, you might want to include the following information in your software development PDD:

- User interface: Most software development projects will include information about the user interface, which is any part of the application or system that allows a software user to interact with it. This section may include information about control states (which control the program’s operations), buttons or menu items, animations, and anything else the user can interact with.

- Inputs: Information that needs to be entered into the application and/or its modules by the programmers.

- Functional requirements: Your PDD will probably include information about functionality, which, as Espy describes it, includes “the specific functions, tasks, or behaviors the system must support.” This section may include details about installation operations, how potential system failures will be handled, how user-created entries in the application or system will be dealt with, and other technical requirements for the application and modules.

- Configuration: If the software will need any special configuration after it’s installed, you may want to include a section explaining what will be involved.

- Milestones: It’s up to your organization to determine whether to list milestones in your PDD. Milestones may coincide with the completion of certain functionality, modules, or applications.

- Data model and storage: This section would describe how and where information is stored in the system (to varying degrees of complexity depending on the organization).

Diagrams and flowcharts are commonly used in software development projects, as well. These help your team and stakeholders visualize the architecture of the application or system, and/or demonstrate the way different parts of the software interact with one another.

Mike Carrol, Project Manager at marketing firm Webb Mason Marketing, says that when creating a website, he often produces a design briefing, initial comps, and a style guide for the client during the project design phase. He suggests referring to the client’s brand standards or guidelines, responsive design best practices, and client industry research to guide you when creating your documentation.

To get a headstart on your PDD, you can use our software development project design template.

Download Software Development Project Design Template - Word

The Project Design Document for Environmental Projects

Environmental project designs focus on reducing the impact of the project on its surrounding environment. These designs require a project design document (PDD) to be reviewed and approved by relevant governing bodies.

The PDD is also a key document used in Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects. These emission-reduction projects are governed by the Kyoto Protocol, and allow countries to trade credits in order to meet emission-reduction targets. CDM projects follow special project design processes and methodologies.

If you are designing a CDM project, a PDD must be created to validate and register your project. The PDD must be reviewed by the Department of Energy (DOE) to make sure it meets validation requirements. The document and the registration request are then submitted by the DOE to the CDM Executive Board for approval.

There are different PDDs for different project types: large-scale and small-scale activities. Large-scale and small-scale afforestation and reforestation projects; and Programmes of Activities (which allow you to register the implementation of an emission-reduction measure, goal, or policy). These projects have specific guidelines regarding content, attachments and revisions, deviations, and public availability of PDDs.

In general, however, a PDD for a CDM project includes the following information:

- A description of the project, including project limitations

- A description of the baseline methodology, which estimates the emissions that would have been produced if the project hadn’t taken place

- The period of time during which the project will take place and the emissions that will be created

- A description of how the project lowers emissions below the levels they would have otherwise reached

- A description of the impact the project will have on the environment

- A summary of public funding sources for the project

- A description of stakeholder feedback and/or expectations

- A description of quality assurance and monitoring processes for the project

- Any other relevant data

5 Expert Tips for Effective Project Design

Effective project design requires you to use resources wisely and have a clear vision of the project’s ultimate goal. Below, you’ll find expert tips to help you create effective project design documents for any industry.

1. Design projects with the ultimate goal in mind. As we’ve discussed, perhaps the most important thing to remember when designing projects is to start with the ultimate goal or outcome and work backwards. Identify the end result you want your project to achieve, and then break it into smaller chunks that each contribute to the ultimate goal.

“In one important way, education is no different than other … verticals in that the most important habit in the project design phase is starting with the end in mind,” says DreamBox’s Hudson.

Wakeman of Wakeman Consulting Group echoes this sentiment. “In any project design, I really try to clarify the intended outcomes as much as possible. In too many projects, the teams get jammed up by the desire to want to create something cool or innovative, but then find the project failing due to no understanding of what the intended outcomes are. So I lead with [an] outcome-based focus,” he explains.

2. Meet with all stakeholders. It’s important that all parties involved be consulted during the project design phase. Hold regular team meetings, and make sure to include all relevant stakeholders in at least the initial session.

“Bring all of the stakeholders ... into the discussion,” says Elyse Kaye, CEO of product development consultancy AHA Product Solutions. “Aligning on goals and pulling innovative ideas from each will help to streamline the process. On countless projects, suggestions or questions come from the most unsuspecting folks, which can help to redefine the whole project.”

Kaye emphasizes the importance of communication with stakeholders. She suggests meeting at least every other week to discuss any issues. “Most projects fail not because the intent, design, or idea was not viable, but because the team was lacking in communication and understanding,” she says. “Work with your stakeholders to agree on the goal, the process, the risks, and the responsibilities.”

Webb Mason Marketing’s Carrol says it’s important to consult with the client during project design. “Listen carefully to the client in initial conversations, and clearly outline ‘must-haves’ versus ‘nice-to-haves,” he says. “Constantly communicate with the client [about] the project status and ... [about any] thoughts that the internal team may be discussing to build client engagement throughout the design process. Pay close attention to the client’s brand standards, if provided.”

3. Consult industry and/or professional association resources. Planning Pod’s Kear recommends finding online project management resources for your industry or specialty to guide you during the project design phase. You may also find it useful to use project planning and design tools like Smartsheet.

“Project management protocols and best practices can sometimes vary from one industry to another,” Kear says. “I would also encourage you to reach out to the local professional organization for your industry, and talk to someone on the board to see if they can introduce [you] to a seasoned pro in [your] industry who has experience with project management. There is no substitute for learning from an experienced professional.”

4. Consult internal resources. Regular team meetings are a cornerstone of project management. These meetings keep everyone on track as the project design phase progresses, and allow you to consult with staff members who can inform the process. Your organization’s internal documentation may also provide you with useful information.

ProjectBliss.net’s Espy recommends, “turning to the team subject matter experts, such as [software] architects and tool product owners, [as well as] other tools and data sources we'll integrate with, and previous design documents. Also, communicate heavily, and ensure you follow your organization's approval processes.”

In the design phase of large-scale projects at BrandExtract, Puente says, “Department heads/team leads meet to review the final approved scope and determine priorities. Here, we'll also flow out all the strategies and tactics, and finalize Gantt charts with the help of project managers. … We might break out into a couple of working sessions, if needed.”

Cazad, of Character.org, suggests that you “determine a point person for each aspect of the project. Outline initial steps for each person, and the process of how they work together. Maybe a weekly debrief meeting is best. Maybe collaborative living documents … work well enough.” She also suggests referring to “survey results, notes, and documentation from projects past, budgets (past and current), [and] previous projects' calendars.”

5. Review and revise as you go. Project design is a complicated process, and your design documentation may need to be updated and edited as you go. Don’t get frustrated if you find yourself making changes, as this is standard practice.

Alona Rudnitsky, Co-Founder and COO of Helix House Digital Advertising Agency, says, “The primary goal for the design process is to move your project through revisions and refinement to find the best solution for the client's problem. It's a way to look at the project from every possible angle and perspective to achieve the solution. It's also a way to not get ‘stuck’ creatively. If you just sit down to a blank canvas and try to paint an entire scene, it can get overwhelming.”

How Third Parties Can Help With Project Design

Project design is a large undertaking, but there are third parties available to assist you. Consultants can aid in project design, or conduct health checks throughout the project lifecycle to ensure it is progressing according to plan.

In the construction industry, design/build firms can assist you with activities such as planning, landscaping, land surveying, and civil engineering, in addition to creating or advising on project designs.

“A good project design not only is a blueprint for construction, but also is a sequential timeline in which workers and materials arrive on site when needed,” says designer Pablo Solomon. “Specifications should be thought out and described for all materials and processes. And all permits and inspections should be timely, accurate, and complete.”

Environmental projects can be especially complex. For CDM projects, there are a variety of online resources, and the CDM Executive Board can also be consulted.

For smaller-scale projects, there are workshops and classes available that can provide the necessary training. For example, the Sustainability Ambassadors is a professional development organization for educators, students, and community leaders who want to educate people about sustainability and the environment. This group hosts a Project Design Lab workshop where attendees learn how to design a project, make proper use of sources, follow performance measures when designing course material, and more.

In any project that will have an environmental impact, “All relevant issues to the environment, from aesthetics to sustainability to low impact to meeting regulations, must be worked out in the project design,” adds Solomon.

Easily Manage Project Design Documents with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.